The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Donizetti Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

Gaetano Donizetti

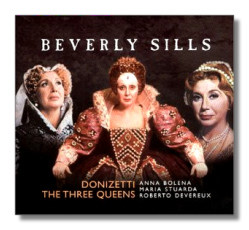

The Three Queens

Anna Bolena

- Beverly Sills (Anna)

- Shirley Verrett (Giovanna)

- Stuart Burrows (Percy)

- Paul Plishka (Enrico)

- Patricia Kern (Smeton)

- Robert Lloyd (Lord Rochefort)

- Robert Tear (Sir Hervey)

John Alldis Choir

London Symphony Orchestra/Julius Rude

Maria Stuarda

- Beverly Sills (Maria Stuarda)

- Eileen Farrell (Elisabetta)

- Stuart Burrows (Leicester)

- Louis Quilico (Talbot)

- Patricia Kern (Anna)

- Christian du Plessis (Cecil)

John Alldis Choir

London Symphony Orchestra/Aldo Ceccato

Roberto Devereux

- Beverly Sills (Elizabeth, Queen of England)

- Robert Ilosfalvy (Earl of Essex)

- Peter Glossop (Duke of Nottingham)

- Beverly Wolff (Duchess of Nottingham)

- Kenneth MacDonald (Lord Cecil)

- Don Garrard (Sir Walter Raleigh)

- Gwynne Howell (A Page)

- Richard Van Allan (A Servant of Nottingham)

Ambrosian Opera Chorus

Royal Philharmonic Orchestra/Charles Mackerras

Deutsche Grammophon 465967-2 ADD 7CDs 64:50, 58:10, 71:26, 74:25, 79:30, 65:54, 69:50

- Beverly Sills (Anna)

- Shirley Verrett (Giovanna)

- Stuart Burrows (Percy)

- Paul Plishka (Enrico)

- Patricia Kern (Smeton)

- Robert Lloyd (Lord Rochefort)

- Robert Tear (Sir Hervey)

London Symphony Orchestra/Julius Rude

Maria Stuarda

- Beverly Sills (Maria Stuarda)

- Eileen Farrell (Elisabetta)

- Stuart Burrows (Leicester)

- Louis Quilico (Talbot)

- Patricia Kern (Anna)

- Christian du Plessis (Cecil)

John Alldis Choir

London Symphony Orchestra/Aldo Ceccato

Roberto Devereux

- Beverly Sills (Elizabeth, Queen of England)

- Robert Ilosfalvy (Earl of Essex)

- Peter Glossop (Duke of Nottingham)

- Beverly Wolff (Duchess of Nottingham)

- Kenneth MacDonald (Lord Cecil)

- Don Garrard (Sir Walter Raleigh)

- Gwynne Howell (A Page)

- Richard Van Allan (A Servant of Nottingham)

Ambrosian Opera Chorus

Royal Philharmonic Orchestra/Charles Mackerras

Deutsche Grammophon 465967-2 ADD 7CDs 64:50, 58:10, 71:26, 74:25, 79:30, 65:54, 69:50

- Beverly Sills (Maria Stuarda)

- Eileen Farrell (Elisabetta)

- Stuart Burrows (Leicester)

- Louis Quilico (Talbot)

- Patricia Kern (Anna)

- Christian du Plessis (Cecil)

London Symphony Orchestra/Aldo Ceccato

Roberto Devereux

- Beverly Sills (Elizabeth, Queen of England)

- Robert Ilosfalvy (Earl of Essex)

- Peter Glossop (Duke of Nottingham)

- Beverly Wolff (Duchess of Nottingham)

- Kenneth MacDonald (Lord Cecil)

- Don Garrard (Sir Walter Raleigh)

- Gwynne Howell (A Page)

- Richard Van Allan (A Servant of Nottingham)

Ambrosian Opera Chorus

Royal Philharmonic Orchestra/Charles Mackerras

Deutsche Grammophon 465967-2 ADD 7CDs 64:50, 58:10, 71:26, 74:25, 79:30, 65:54, 69:50

- Beverly Sills (Elizabeth, Queen of England)

- Robert Ilosfalvy (Earl of Essex)

- Peter Glossop (Duke of Nottingham)

- Beverly Wolff (Duchess of Nottingham)

- Kenneth MacDonald (Lord Cecil)

- Don Garrard (Sir Walter Raleigh)

- Gwynne Howell (A Page)

- Richard Van Allan (A Servant of Nottingham)

Royal Philharmonic Orchestra/Charles Mackerras

Deutsche Grammophon 465967-2 ADD 7CDs 64:50, 58:10, 71:26, 74:25, 79:30, 65:54, 69:50

This was the reissue event of the year 2000, at least in the world of operatic recordings. As far as I can tell, only the Anna Bolena was on CD before now, and that in a hard-to-find edition lacking even a libretto. The neglect is difficult to understand. Beverly Sills was a tremendously popular soprano thirty years ago – at least in the United States – and many of her fans still are around and, I am guessing, more than ready to replace their vinyl LPs. Furthermore, good studio recordings of these three operas are not thick on the ground – and these recordings are better than good. Even "live" recordings of Roberto Devereux are uncommon. So, there's plenty to love here for fans of both "Bubbles" and Gaetano Donizetti. These recordings originally were issued by Westminster/ABC Records, and it is a surprise to see them reappear on Deutsche Grammophon; I would have expected them to be reissued by EMI Classics, as all but Maria Stuarda were recorded at EMI's London studios.

Anna Bolena (Anne Boleyn) is the most popular of the "Three Queens" operas. As with the other two, it plays fast and loose with English history. For example, the operatic Anna has an effective "Mad Scene" and dies before the headsman can get to her. In essence, the opera is about a queen who inadvertently ruins those who love her most; the body count as the final curtain rings down is not small, and even Giovanna (Jane) Seymour, her successor in Enrico (Henry) VIII's bed, is far from triumphant. This is a long score, and it is common for it to be cut drastically. Sills's set is an hour longer than Callas's live La Scala performance, as reissued on EMI Classics, and even the Sills, I believe, is not as complete as Sutherland's studio recording. (The Callas, then, is wonderful theater, but it does Donizetti no favors.) Donizetti's music is not consistently first-rate, but it never bores, and there are several superb arias and scenes. Among the latter, one must count the Act I duet for Giovanna and Enrico, and the Act II duet for Anna and Percy. This latter duet culminates in Enrico's discovery of Anna's supposed infidelity, and the succeeding sextet rivals the parallel ensemble in Lucia di Lammermoor if nor for melody then for skill of construction. The Mad Scene, already noted, is masterful, as the moribund Anna's gentle distraction turns to righteous anger against Enrico and Giovanna. "Coppia iniqua" (Wicked couple) she calls them, to dramatic vocal fireworks. This is writing that cries out for 20-minute stamping, standing ovations.

This set was recorded in 1972 (the last of the three) and what a cast it has! Sills, as always, is touching and brilliant, and if she makes some strange sounds now and then, there's no doubt about her involvement in the title role. Shirley Verrett matches her blow for blow; what a fine singer she was then; there is no hint of the vocal deterioration that would plague her in the succeeding decade. Giovanna's coloratura holds no terrors for her, and the assurance of her technique – every note is hit dead on – is matched only by her assured interpretation. Her Act II duet with Sills is a singers' orgy of sympathy, betrayal, and forgiveness, and it is one of the set's highlights. Burrows is a mellifluous Percy, and his aria in the Tower of London scene make one wonder why he didn't record more of the Italian repertoire. (Admittedly, his stratospheric high notes in the cabaletta are not comfortable, but he gives them a good try.) A young Paul Plishka is a sinister Enrico, and the smaller roles are handled well. Patricia Kern even does a creditable job with Smeton's frequently cut aria in the third scene of Act I. Conductor Julius Rudel is dependable and sympathetic – certainly equal at least to Sutherland's Bonynge – and the chorus sings with dramatic involvement. All in all, everyone makes a bid to push Anna Bolena into the standard repertoire. If only a cast like this could be assembled today!

The confrontation between Anne Boleyn and Jane Seymour pales between that of Maria Stuarda (Mary Stuart) and Elisabetta (Queen Elizabeth); in public, the Queen of Scotland impugns the Queen of England's legitimacy with words so strong that the censors stepped in to protect the public. The two singers who first took on these roles hated each other offstage as well as on, and one rehearsal ended with Elisabetta punching Maria, who in turn knocked her rival down and pummeled her. (And you thought "Celebrity Death Match" was just a sick fantasy!) As in Anna Bolena, Donizetti is given the opportunity to write an extended scene for a queen on the verge of execution, but here, Maria loses her head but not her wits, and prays that her unjust execution may "soothe the wrath of outraged heaven," rather than calling down God's vengeance. It's another great moment for a reigning soprano. Musically, Maria Stuarda is only a little less distinguished than Anna Bolena, possibly because the libretto is inferior. Again, there's a culminating sextet, and highly effective duets for Leicester and the two queens. Maria's so-called "Absolution Scene" also contains yards of Donizettian cantabile writing at its best.

Sills's Maria Stuarda was recorded in 1971. She and Burrows are as strong as they were in the later recording; the soprano summons up even greater reserves of power and vehemence for the outraged heroine, yet elsewhere her singing has a melting tenderness wedded to a solid care; the same can't consistently be said of Sutherland in her recording of this work. Farrell, who, inexplicably, hardly ever recorded a complete opera (yet this was not her first, regardless of what the libretto's bio says), spits fire as Elisabetta, and her confrontations with Maria and Leicester are thrilling. Like Verrett, she hits notes with laser-like accuracy and definition, and she gives her character 110 percent. Kerns returns in the smaller role of Maria's confidante, Quilico is stylish as Maria's friend and confessor, and du Plessis does well as Elisabetta's ambitious advisor Cecil. Ceccato is a sympathetic conductor who doesn't get in the way of the singers or the music. He's not as vivid as Rudel, but he gets the job done, and then some.

I was startled by Deutsche Grammophon's assertion (on the jewel box's back cover) that Roberto Devereux is the best known of the Three Queens operas; I would have said the opposite. Nevertheless, it was the first of the three to be revived by the New York City Opera, and the first to be recorded by Sills (in 1969). If you've ever seen Bette Davis and Errol Flynn in The Private Lives of Elizabeth and Essex, you'll know what happens in this opera: Elisabetta (Queen Elizabeth) agonizes over whether or not to pardon her younger erstwhile lover Roberto (Robert Devereux, the Earl of Essex) for his disobedience to her in Ireland. The situation is complicated by Roberto's love (returned but unconsummated, we are made to believe) for Sara (Sarah, the Duchess of Nottingham). In Act II, Elisabetta and Nottingham discover what their respective lover and wife have been up to – or so it seems – and their rage and jealousy drive the action to its end. In this opera, it is Roberto, the star tenor, who goes to the block, but it is Elisabetta who loses her wits, at least for the moment, imagining Roberto's decapitated ghost running through the palace with a bloody, severed head in its ghostly fist. This (you guessed it) is another excuse for soprano fireworks, and Donizetti rises to memorable heights here. Elsewhere, the music in Roberto Devereux is a little more routine than in the other two operas, but it is not hard to be swept away by the action, which is more concentrated. This is the most intimate of the Three Queens operas; even the chorus seems to be tip-toeing around most of the time.

In this opera, the soprano is less the martyr and more the wronged woman, and Sills responds with effective use of her chest voice and venom-spitting characterization. The coloratura element is not shortchanged, however, and the pseudo Mad Scene contains thrillingly florid writing and a final high D that Sills nails. She prepared extensively for this role, and just as ads in the 1960s proclaimed, "Callas is Carmen," Sills "is" Queen Elizabeth. Robert Ilosfalvy's singing makes one wish that Burrows (or Plácido Domingo, Sills's partner on stage) had recorded Roberto's role instead. Ilosfalvy's light, flexible voice has approximately the correct timbre for this role, but he is not dependable about pitch, and his sliding between notes is a sloppy excuse for legato. Still, he is dramatically apt. Mezzo-soprano Beverly Wolff joins Verrett and Farrell in going head-to-head with Beverly Sills – both vocally and dramatically – and not sounding like a second fiddle. Wolff is most impressive at the end of Act I, when she and Ilosfalvy take their leave of each other. Her singing is rock-solid and exciting, and she seems to have an endless supply of lungpower. (I was not surprised to read that she once was an accomplished trumpeter.) Glossop doesn't make as much as he might have of Nottingham's switch from Roberto's supporter to his foe; more Renato-like vindictiveness would have made his portrayal more vivid. Kenneth MacDonald is a nasty Cecil, and Don Garrard a sonorous Raleigh. Gwynne Howell and Richard Van Allan, both major singers, appear in minor roles. Mackerras is a sympathetic and understanding conductor. This recording has the most extreme sound effects; Roberto clanks around in the Tower of London, and when his cell door opens, you expect the host of "Inner Sanctum" to be on the other side. There's also a highly unnecessary general scream, more appropriate for natural catastrophes, as Roberto loses his head offstage.

Deutsche Grammophon decided to reproduce the original LP cover art and libretto material for all three operas. This might appeal to the nostalgia-bitten; no doubt it was an inexpensive decision. However, the typographical errors are distressingly numerous, what is sung is not always what is printed, and the artist biographies trail off circa 1973. Sills's contributions to the arts have been so notable in the last thirty years that it seems mean not to credit her for them. Most of her fellow singers are no longer active, and it also strikes me as an injustice that their full careers have not been reviewed, even briefly, at this time. A slip-case sized booklet is new, however. It contains an essay by reissue producer Anthony J. Rudel (conductor Julius Rudel's son?) and lots of photographs. Among the latter, my favorite is one of Sills rehearsing Roberto Devereux at the New York City Opera with a young and decidedly plump Plácido Domingo, who is wearing a most impish grin.

I think it was ham-fisted of Deutsche Grammophon to release all three operas together. (Perhaps they will be made available separately later.) Nevertheless, if you want one, you'll probably want them all, so break open the piggy bank and revel in the royalty of Beverly Sills and Gaetano Donizetti.

Copyright © 2001, Raymond Tuttle