The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

-

Boulanger Reviews

Stravinsky Reviews - Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

Psalms

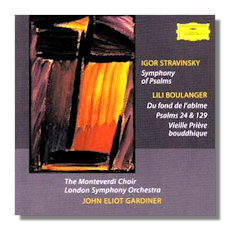

- Lili Boulanger:

- Psalm 24 "La terre appartient à l'Éternel"

- Psalm 129 "Ils m'ont assez opprimé dès ma jeunesse"

- Psalm 130 "Du fond de l'abîme" (Out of the Depths)

- Vieille prière bouddhique

- Igor Stravinsky: Symphony of Psalms

Sally Bruce-Payne, mezzo-soprano

Julian Podger, tenor

The Monteverdi Choir

London Symphony Orchestra/John Eliot Gardiner

Deutsche Grammophon 463789-2 68.08

Had she not died at the age of 25, Lili Boulanger (1893-1918) would, by many acounts, be regarded as a major French composer. As it is, her compositional accomplishments overshadowed those of her better-known sister Nadia, who mostly gave up composition and devoted her life to training many American neo-classical composers. As it is, currently at Arkiv there are 35 recordings of Lili's music and on Amazon there are eleven. There have been at least two books devoted to Lili Boulanger's short musical career: LeIonie Rosenstiel's "Life and Works of Lili Boulanger"; and Caroline Potter's "Nadia and Lili Boulanger". She read music at age two and a half; at five Gabriel Fauré accompanied her on his songs; she began serious study of harmony at six, and at nineteen won the Prix de Rome with a cantata, Faust et Hélène, which Debussy praised. The works on this recording date from 1916 and 1917 and they impress me much more than the few other works by her I have heard. This is music that is both powerful and beautiful.

At about twenty seven and a half minutes, Du fond de l'abîme is the longest work on this disc, although the text is relatively short. Its first minutes are soft and quiet – the chorus even seems to sigh at one point – but by a third of the way through it becomes first quietly then fiercely dramatic, with brass, drum rolls and loud singing. There is a big crescendo augmented by the organ toward the end. The orchestration is impressive, but does not overwhelm the strong voices, and is often quiet; there is an opportunity for the mezzo to have solos and for the tenor and mezzo to sing together over light accompaniment.

Psalm 24 for chorus, organ and orchestra, which opens the disc, is less than four minutes long but begins with a powerful fanfare and the male choir sings full out. It softens and slows, with a horn solo, but again becomes emphatic with brass and organ. Psalm 129 for chorus and orchestra, at seven and a half minutes, opens with slow and low thrusting tones and the orchestra plays for two minutes before the chorus enters powerfully; there is rising tension and emphatic rhythm with beating drums, but at the end voices become gentler and the female choir sings wordlessly over the males and then alone.

The Buddhist prayer (Vieille prière bouddhique) for tenor, chorus and orchestra lasts for eight and a half minutes and opens slowly and beautifully with the male choir accompanied by a higher vocal line; high strings play later also. There is a nice Debussy-like flute solo. The tenor is not heard until the mid-point. The final minutes are loud and powerful.

The commentator Roger Nichols says that "the music of these four works was not what a well-brought-up jeune fille was expected to produce, let alone one in poor health". He also notes that her melodic lines are "extraordinarily bold and wide-ranging, often negating any sense of key." She makes use of semitones.

The performance of Stravinsky's work for chorus and orchestra on texts from Psalms 38, 39, and 150 is excellent and the recording is better than the recent Rattle release (EMI Classics 2-07630-0), which I have reviewed here, so I am not going to say much about the work in this one. The first movement strikes me as just about perfect. The oboe solo opening the middle section is quite satisfying and the Monteverdi Choir is impressive here, as in the Boulanger. The male voices are especially powerful. The gorgeous "laudate" movement is well paced, well articulated in the staccato passages and has subtle dynamic emphases in the legato ones. I was struck by a beautifully built crescendo near the midpoint of the movement.

Strongly recommended.

Copyright © 2009, R. James Tobin