The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Bruckner Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

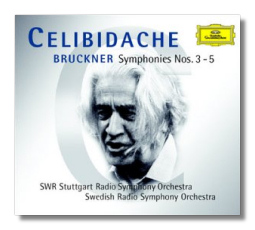

Anton Bruckner

Middle Symphonies

- Symphony #3

- Symphony #4 *

- Symphony #5

- Wolfgang Mozart: Symphony #35 ("Haffner")

SWR Stuttgart Radio Symphony Orchestra/Sergiu Celibidache

* Swedish Radio Symphony Orchestra/Sergiu Celibidache

Deutsche Grammophon 459663-2 ADD/DDD 4CDs: 61:14, 69:02, 58:44, 41:06, plus a 39:19 bonus disc

This set complements Deutsche Grammophon's earlier release of Celibidache conducting Bruckner's Seventh, Eighth, and Ninth Symphonies (DG 445 471-2). These, like their predecessors, are live recordings. The Fourth ("Romantic") was recorded in 1969 with the Swedish Radio Symphony Orchestra, while the orchestra was performing in Berlin. The Third and Fifth Symphonies were recorded in 1980 and 1981, respectively, in Stuttgart. The Fifth is this set's only digital recording. The Mozart "Haffner," which serves as a makeweight for Bruckner's Fifth, was recorded in 1976.

There was no one quite like Celibidache. He avoided making studio recordings, believing that they were a falsification and a fossilization of musicianship. Since his death, his family has permitted the release of select concert recordings by EMI Classics and Deutsche Grammophon. In so doing, they hope to preempt the flood of unauthorized and potentially inferior recordings that unavoidably results when the work of a cult musician enters the public domain.

These were memorable concerts. It was relatively late in his career that Celibidache earned his reputation as a Bruckner specialist. Whether one likes these performances or not, one cannot deny that they are the product of the conductor's intense intellectual application, as well as his spiritual sensitivity to sound. As such, any listener who loves Bruckner's music must hear them, because they will teach him or her much.

There are many challenges to the status quo here. For example, the opening paragraph of the Third Symphony – characterized by an almost conversational approach to phrasing – will seem incredibly self-indulgent to some, and revelatory to others. Or, to give another example, Celibidache has completely rethought tempos in the last movement of the Fourth Symphony, even earning the approval of the British Bruckner scholar (and a fine composer in his own right) Robert Simpson. The result will seem brutally slow, but one can't deny the conductor's logic, and the emotional impact – at least for me – is overwhelming. Here, as in his other Bruckner performances, Celibidache shifts the weight of the symphony from the first movement to the last. In Simpson's words, "Sergiu Celibidache has magnificently shown that the whole of the Finale is really an adagio."

The Munich Philharmonic readings on EMI Classics are the slowest of all. In 1987, Celibidache's total timing for the Third Symphony was 65:32, four minutes slower than the Stuttgart reading released here. The timing for the Fourth was 79:11 in 1988, ten minutes slower than this Swedish reading. It might be said, then, that these Deutsche Grammophon recordings show Celibidache traveling towards a destination that he has almost reached in his Munich recordings. Those who find Celibidache's last performances too extreme still might be convinced by the performances included in this set.

Understandably, the brass tire near the end of each work, particularly in the Fifth Symphony. Otherwise, the orchestral playing is excellent, although I have a slight preference for the sound of the Munich Philharmonic. There were times when the musicians in Celibidache's orchestras were required to play in an unconventional manner. For example, Celibidache asked string players to draw their bows across the strings more slowly and heavily than other conductors did. If a soloist played like this all the time, it would sound strange indeed, but if an ensemble plays like this, the effect can be magically full and intense. It is techniques such as this one that give any orchestra, even those not in the world's uppermost class, the "Celibidache sound" (if such a worn-out cliché can be repeated) no matter how taxing the playing conditions.

Mozart's "Haffner" receives a dashing performance. Celibidache plays a cat-and-mouse game with dynamics in the symphony's opening phrase, and from there to the end of the work there's never a dull bar. The slow movement is lovely (although never completely relaxed), and the finale is treated as a virtuoso showpiece. It's not a Mozartean reading, but it works.

The bonus disc contains excerpts of a rehearsal of the Fifth Symphony. These, of course, are in German. No texts and translations are provided, so this bonus is of limited value for those who don't understand German.

Celibidache frequently spurs the orchestra on with harsh yells during the Third Symphony, and this can be frightening until you figure out what it is. There are occasional audience sounds, but no applause. Although these recordings were not originally intended for commercial release, the sound is fine, just short of studio ideals. This is tribute not just to DG's current remastering technicians, but also to the original engineering team, who could not foresee the reputation that Sergiu Celibidache would have in the year 2001!

Copyright © 2001, Raymond Tuttle