The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

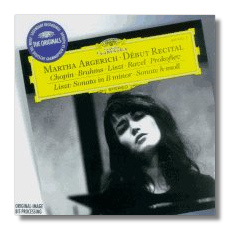

Martha Argerich

Début Recital

- Johannes Brahms: Rhapsodies, Op. 79

- Frédéric Chopin:

- Barcarole in F# Major, Op. 60

- Scherzo #3 in C# minor, Op. 39

- Franz Liszt:

- Hungarian Rhapsody #6

- Sonata for Piano in B minor

- Serge Prokofieff: Toccata, Op. 11

- Maurice Ravel: Jeux d'eau

Martha Argerich, piano

Deutsche Grammophon 447430-2

I can't imagine anyone indifferent to Martha Argerich's playing. To me, she would inspire either fierce love or fierce hate. I find myself a partisan. This remarkable debut album (except for the Liszt sonata, made when the pianist was 19) has value not only for documenting an auspicious beginning, but in its own right as an exemplar of, at the least, brilliantly imaginative piano technique and musicianship.

I admit I'm a klutzy piano player, at best a duffer, so I have really little idea of technique. However, I do know the difficulty of clear projection, clean textures, and color variation - in short, all the things missing from my playing. With Argerich, each note is both distinct and part of a longer line - each glistens like dew on a spider web.

The program opens with a bang - Chopin's third scherzo - and one immediately meets a singular sensibility with the fingers to express itself. For me, there are two kinds of Chopin players: Apollonian and Dionysian - those who aim at some ideal, unchanging interpretation and those who, like jazz players, allow themselves to ride the musical wave, to discover things while they play. Both players run risks. The Platonists can fall into stultification. The Bacchantes can become merely eccentric or the performance can simply break apart into chaos. The Platonist's reward is a kind of "naturalness." Perfect beauty seems to come from "just playing." The Dionysian's reward is ecstatic discovery. It forces the listener to "hear anew." Argerich clearly belongs to the second group. That at so young an age she could bring off something so individual and so right amazes me. No wonder the Poles went nuts.

Nothing in the interpretation betrays the music. Still, the interpretation remains one-of-a-kind. Argerich chooses to emphasize the instability of the piece. The opening measures harmonically and rhythmically leave the listener up in the air. The confusion lasts only a moment, as she launches into the main strain. This unleashes a demonic energy, which runs smack into a chorale idea. This usually signals pianists to switch straight into their "nobilmente" gear. Yet, Argerich doesn't take it straight, preferring to contrast the chords with a glittering arpeggio. Again, this destabilizes the texture, leading to (after the reappearance of the chorale idea) an inexorable rush to the end. What Argerich has done, in contrast to other pianists, is essentially extend the arch of the piece. Her command of dynamics and color here is superb.

On the other hand, the Brahms rhapsodies reveal her limitations. Not that anything is downright awful, but the Chopin has led you to expect the extraordinary. For Brahms, in the words of the old Mae West song, "I like a man what takes his time." Argerich rushes here, and furthermore her tone lacks weight. The left hand, particularly the low bass, is just too light (a fault, by the way, that also besets her Liszt Hungarian Rhapsody). I wanted every section slower, savored, lingered over, including the slow sections. Often it's just a hair's breadth of difference. For me, the second rhapsody fares better than the first, with a nice mysterioso in the second rhapsody's cortege-like lyric subject. However, by the time of her recording of the Liszt piano sonata eleven years later, she seems to have worked through both problems.

The Prokofieff and the Ravel resemble each other, in that their composers designed them to make your jaw drOp. Both rely on a constant undercurrent of smaller note values, which lead some players to emphasize a "sewing-machine" rhythm. Argerich, however, always seeks out the larger phrase, and, in the Prokofieff especially, this isn't easy. The Prokofieff not only percolates, but curiously it shows the heft missing in the Brahms. Again, each note has its own identity and yet belongs to a constantly moving musical line. In both works, one hears a mastery of shifting color, almost orchestral in its resource. One not only hears water in the Ravel, but different kinds of water, from spray to deep current.

Again, the Hungarian Rhapsody disappointed me a bit - rushed and too light. Despite the flash, Argerich makes nothing of the musical inventiveness in the piece, particularly the unusual harmonic cadential figure in the fast "repeated-note" sections of the piece - VIb,V,I in the bass. I favor Ivan Moravec and Leslie Howard here.

Nevertheless, I find her account of the Liszt sonata stunning at all levels. Obviously, her hands have mastered the notes. However, her ability to find the music in all the notes amazes me. I should say that I've never particularly liked the Liszt sonata, or any 19th-century sonata after Schubert. The Liszt in particular has always seemed to me a compendium of cliches and over-reliance on diminished triads and sequence. I've heard Horowitz's EMI recording, Brendel, and Arau. I've not heard my two all-time favorite Lisztians, Cziffra and Howard, in this particular work and, in fact, don't know whether recorded performances exist. Schwann is silent.

The Liszt bears as much resemblance to classical sonata form as a platypus does to a duck. The trick for the pianist is to overcome the obviously sectional nature of the work and make the listener forget that each section is more than a rush to another climax - a tall order, since that's practically Liszt's entire rhetorical strategy. Under hands only vaguely connected to the brain, the piece comes off as a garage sale of spare parts. Argerich shows you how Liszt builds an impressive structure from two or three little bits, not even full-fledged themes, and how the composer's incredible sonic imagination (allied, I'm sure, to his miraculous technique) inventively transforms these bits into new themes, rhythms, and textures. One reads about this in essays on the subject, but Argerich is the first to show this in action. I never realized to what extent the opening downward run in the bass generated the thematic transformations before. It leads to an all-important "repeated note" gesture (4 repeated notes, a little downward fillip, and an upward leap, followed by a chromatic descent of 2 notes), which in turn leads to an important lyrical idea, varied just enough in rhythm and tempo to disguise its parentage. At other points, Liszt breaks up the idea among widely disparate registers. "Repeated note" even gets a fugal treatment. Stuff like this happens throughout the sonata. To Argerich's immense credit, she never loses the thread or the listener.

However, not everyone listens for this kind of thing, and if the performance consisted of only this, a computer-generated account would suffice. Argerich brings even more, leaving aside the sheer physical excitement of her playing. Listening to the disc a number of times, I've discovered that she routinely builds incredibly long spans of music. She not only knows how to shade a phrase through sensitive, momentary builds and releases, she carries this method over longer spans. She knows precisely not only where the high point of a phrase or a section lies, but of an entire piece, even one this long. Other great pianists do this as well. In fact, this for me practically defines a great pianist. The buildup of volume comes more easily than the release, because it's a primary device of increasing tension and excitement, just as getting faster is. Unfortunately, a player might reach his peak before the music. This occasionally happened to Bernstein, particularly in Richard Strauss. He needed to get louder, but had already shot his dynamic wad, so to speak. The release is much harder: a player often just loses focus and the piece momentarily dies. Argerich always has someplace to go, up or down, and reaching the valley is just as urgent as attaining the summit. The rapid octaves leading to the long, "dying fall" of the coda demonstrate this clearly.

Magnificent.

Copyright © 1998, Steve Schwartz