The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Bartók Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

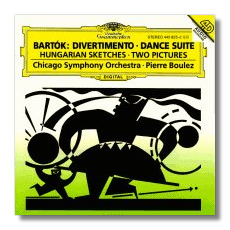

Béla Bartók

- Dance Suite

- Two Pictures

- Hungarian Sketches

- Divertimento for String Orchestra

Chicago Symphony Orchestra/Pierre Boulez

Deutsche Grammophon 445825-2

One of my Hungarian ancestors has a street named after him in Budapest. The street runs by the casino – appropriate, due to his compulsive gambling. Somehow, Bartók's music – and not just because of its use of folklore – reminds me of the Hungarian side of my family. A great-great-uncle lived only in hotels and, whenever he got paid (sporadically, I gather), he used to dump the money out on the big round table my great-great-aunt used for strudel pulling. The Hungarian ancestor with the street used to regularly commute between Budapest, Prague, and Vienna in taxicabs and once wrote a pamphlet on the proper way to commit suicide (incidentally, he didn't follow his own advice). My own grandfather taught himself English through Shakespeare and the Tieck-Schlegel translation of Shakespeare. To the end of his life, he used words like "fardel" and "patines" (mispronounced, since he never heard anyone else using them). So I think of my Hungarian relatives as stubbornly eccentric and, in one or two cases, oddly and flamboyantly brilliant, like a gypsy fiddler.

Yes, yes, I know Bartók is a Modern Master. If nothing else, Grove tells me so, but that's just as if one of my great-greats had turned out to be right all along, instead of just plain nuts. I'm trying to say that, for me, Bartók has a wide streak of brilliance in him, typified for me by the second piano concerto or the end of the fifth string quartet. Just because he is a Modern Master doesn't mean we should be pulling long faces, as if we're in church. "Brilliance" implies not only diamonds but fireworks.

For these reasons, I'm drawn to those conductors who proudly show off the crazy uncle in Bartók's basement – people like Reiner, Solti, Doráti, and Kubelík. I once heard a stunning live performance of the Miraculous Mandarin suite with Boulez and the Cleveland that rubbed my nose in the bizarre elements of the score. I can't imagine what happened to Boulez in the meantime. Certainly the Chicago Symphony Orchestra gives him everything he asks for. Unfortunately, most of the time, what he asks for is an official portrait, rather than the living music.

In the Dance Suite, Boulez gets some incredibly refined and subtle playing from the Chicago players, and I have problems with that. It's a suite of peasant dances, after all. To its advantage, the Chicago is rhythmically spot on, always good in dances. Nevertheless, the performance reminds me somewhat of Kiri Te Kanawa singing Little Richard. It just don't swing. To me, it's not the players. Chicago has proven again and again that it is a great Bartók orchestra. Boulez seems bent on turning Bartók into a Grand Old Man.

I must admit Boulez's refinement works to great effect in the early Two Pictures. The first movement broods (in a Bartókian twist on Debussy impressionism), and Boulez keeps the dynamic lid on and the textures clear, so that when the orchestra finally erupts, it's like a punch in the stomach, and he does it all with no more than a forte. The second movement comes off less well, and again the culprit is Boulez's reluctance to allow the new orchestral sounds their full strangeness. How does one belch refined? Again, however, the Chicago playing is spacious and bright. Furthermore, one hears the quick riffs of the second movement tossed off with rare clarity and precision.

On the other hand, the Hungarian Sketches are an unblemished delight, from the opening woodwind solos, alternating melancholia and gaiety, to the lively evocation of fiddle music in the finale. Here, Boulez gives you all the subtlety and his understated approach doesn't inflate this showpiece beyond its limit.

The Divertimento comes off as a mixed bag. On the one hand, the canonic writing is clear as Steuben. On the other, the pesante chords recall less tromping and more of the ballet. Frankly, I prefer Eugene Ormandy's version with the Philadelphia. At least I didn't feel as though I had to wear a tie.

Copyright © 1996, Steve Schwartz