The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Pettersson Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

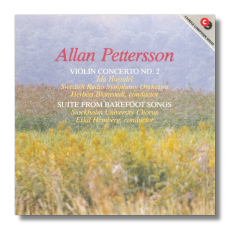

Allan Pettersson

- Concerto #2 for Violin and Orchestra

- Suite from Barefoot Songs

Ida Haendel, violin

Swedish Radio Symphony Orchestra/Herbert Blomstedt

Stockholm University Chorus/Eskil Hemberg

Caprice CAP21359

I first happened upon the music of Pettersson at least twenty years ago. I came across an old LP with Antál Doráti's orchestrations of eight of the twenty-four Barefoot Songs – a wonderful recording which I hope will show up some day on CD. The album included no printed texts, and since I speak no Swedish, I had no idea of the lyrics' content. What I heard, however, were absolutely ravishing melodies, a piquant blend of Grieg and Mahler. I assumed I was listening to Swedish Pastoral, à la the more popular works of Lars-Erik Larsson, and I couldn't have been more wrong. The symphonies came, consequently, as a shock. Pettersson's voice is never that simple.

The Barefoot Songs appear early in Pettersson's compositional career (he came to composing relatively late), before he finds his mature voice. To a great extent, he tries out the Romantic Scandinavian idiom in the early to mid-1940s, but then drops it for his more representative granitic musical language. However, even here, the proud, angry, uncompromising Pettersson touches the work in the poems (by Pettersson himself). In them, God wanders in beauty, far from those who need him most, a child is abandoned, life is brief and hard, humans treat one another badly – and all to incredibly beautiful, lyrical music. The tension of the pieces arises from the conflict of tune and text.

I suspect that most people don't really listen to lyrics anyway (how else does one explain Lionel Richie?), because the work is one of Pettersson's most popular, even beloved. Doráti's orchestration and recording probably introduced most North Americans to the composer, and in 1969 Pettersson asked choral composer and conductor Eskil Hemberg to arrange some for mixed choir (the originals call for voice and piano). The differences between Doráti and Hemberg I find interesting. Doráti emphasizes the links to the Mahler orchestral song, Hemberg to the Romantic part-songs of Schubert, Mendelssohn, and Brahms. Now I'd like to see a recording of the complete group in the original, to hear what the composer actually had in mind. The performance typifies the Scandinavian approach to choral singing: a bright, clean sound, smack in tune, and a bit light or "white" in the treble voices. The soprano soloist's voice is still a little young, with a bit of forcing in the upper registers and a slight weakness at the lower end of her range. Still, it's not unpleasant, and emphasizes the faux naïvete of the poems.

The Violin Concerto #2 connects with the Barefoot Songs (Petterson uses one for thematic material), but if not from a completely different world, it at least has spent time in a rougher psychological neighborhood. If we believe psychiatrists, most of us suffer some sort of childhood trauma. Pettersson had one in spades: a brutal father who beat him when he expressed the wish to become a musician and an alcoholic, victimized mother who sought refuge in piety. He grew up in the poorest slums of Stockholm and somehow became a leading virtuoso violist. You would think he had overcome trauma, but another hit him as an adult: crippling rheumatoid arthritis which destroyed his performing career. I have an acquaintance with the disease myself. Without going into too much detail, it follows a cyclical course: intense, cold pain in the joints, at times literally crippling, followed by short respite, during which the disease seems to go into remission. This gives the sufferer hope, usually destroyed by another wave of pain. Eventually, one learns resignation. In addition, over the long haul, rheumatoid arthritis ravages the joints and the skeleton itself. Pettersson could barely walk without crying out. How he wrote music – the physical act of putting all those notes to paper – I'll never know.

To me, the disease finds its way into the concerto, one of the most massive in the literature. The work runs in a single movement, slightly under an hour, but in two large sections. It's hard listening, I'll be the first to admit, but if you can hook up with it, it definitely will reward you. What makes it hard is that Pettersson doesn't really work with song-like themes, despite the fact that many of the building blocks come from one of his songs. He works at an almost microscopic level of detail – a few notes, a characteristic rhythm, which he then almost immediately varies. In the first part of the work, I counted at least ten distinctive motifs, and many of those varied one another. Furthermore, the melodic lines of the work are highly chromatic and feed upon themselves, like the Dies irae (which itself makes a brief appearance in the first section). The lyric section resembles the old French chanson "Adieu mes amours," but I doubt this is intentional. Psychologically, the first part is an almost unrelenting cry of anger and pain. In fact, the liner notes quote Pettersson himself: "I am no composer, I am a voice crying…." Gradually, lyric, consoling elements creep in, so that the concerto becomes a battle as to which will win out. At times, the music becomes almost triumphant, only to fall back into Angst. Finally, in roughly the last two-and-a-half minutes, a chorale idea leads to something like hard-won triumph, but not to a triumphant blaze. Again, nothing is simple with Pettersson. If the anguish of the work has temporarily taken its leave, the concerto still ends, "weakly," on a question.

Ida Haendel, the soloist and dedicatee, does a phenomenal job with an essentially ungratefpart. She's "on" at full intensity almost throughout the near-hour. Furthermore, the concerto doesn't give her the chance to play the dashing heroine (as in the Tchaikovsky) or the wise woman (as in the Beethoven) or the sweet singer (as in the Mendelssohn). She's very much a team player, a part of the instrumental fabric, sometimes thrown into momentary relief, mostly prima inter pares. The concerto doesn't spotlight a soloist. Even while the soloist plays, material of at least equal interest sounds in the orchestra. Pettersson concerns himself almost entirely with his musical message, rather than with concerto-theater. To this extent and in the demands it makes upon the concentration of everyone involved (soloist, conductor, orchestra, and listener), it reminds me a bit of the Schoenberg concerto.

I can't really say how well Blomstedt and his orchestra do, since this is the only recording. At first, the performance seemed a bit shapeless, but as I listened, I began to discern the sections. Still, dynamics are almost always full out, and modulations are practically impossible to discern, even though this music is tonal. Pettersson thus eschews two of the main ways composers build long movements. One apprehends sections almost entirely by new musical gestures. Since at least three different things go on at any given time and the music "evolves" rather than "develops" in the conventional sense (new variants and new motifs are continually introduced), you don't arrive at a new section, as much as you suddenly find yourself in the middle of one. Would another conductor find a more definite aural thread? Hard to say.

The recorded sound strikes me as downright ugly, but others who have heard the disc disagree with me. To me, it's all too closely miked, probably the result of engineers trying to get everything audible and makes me think they fit everybody into a rain barrel. In spite of this, the piece strikes me as a monument of postwar music – to quote Frank O'Hara, "a real right thing."

Copyright © 1996, Steve Schwartz