The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

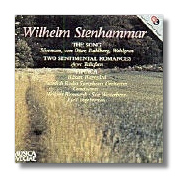

Wilhelm Stenhammar

- Sången (The Song) 1

- 2 Sentimental Romances 2

- Ithaka 3

Iwa Sörenson, soprano

Anne Sofie von Otter, mezzo-soprano

Stefan Dahlberg, tenor

Per-Arne Walgren, baritone

1 Swedish Radio Choir

1 Chamber Choir of the State Academy of Music in Stockholm

1 Adolf Fredrik Music School Children's Choir

2 Arve Tellefsen, violin

3 Håkan Hagegård, baritone

1 Swedish Radio Symphony Orchestra/Herbert Blomstedt

2 Swedish Radio Symphony Orchestra/Stig Westerberg

3 Swedish Radio Symphony Orchestra/Kjell Ingebretsen

Caprice CAP21358 57:06

Summary for the Busy Executive: Mostly terrific.

My first encounter with Stenhammar's music turned out a fluke. Although a virtuoso pianist, he wrote very little for his instrument. Naturally, I first heard two very powerful piano fantasies (two of the three Fantasies, Op. 11), also atypical of the composer's style, sounding more like the Rachmaninoff of the second piano concerto. Still, they made me mark Stenhammar as a composer to look for.

Stenhammar in many ways strikes me as an "unfinished" composer - not in craft, but in finding his voice. He died in his fifties and suffered through at least one very long creative block. He also had a substantial career as pianist and conductor. Among other things, he was the first in Sweden to take up Mahler. Items in his catalogue differ substantially in idiom. He tries on a lot of voices as he works toward one of his own. For me, he sounds most at ease in an idiom based on Swedish folk music, combined with rigorous craft, Romantic expression, and imaginative counterpoint. Works of this type include his Symphony #2 in g-minor and the Serenade in F Major, as well as the fifth string quartet (subtitled "Serenade"), all fairly late. But I'm not inflexible about it. You can find wonderful items in his catalogue throughout his career.

The three items on the program come from all over Stenhammar's composing career - from Ithaka of 1904, to the Two Sentimental Romances of 1910, to his final completed work, The Song of 1921. I would deal fairly shortly with the Sentimental Romances. They're very well and very sparely written. However, they're also salon morceaux. They don't aim all that high, and, and after they finish, they disappear from consciousness like fog in sun.

The other two pieces are, to my mind, magnificent. They sound the way you think Nordic music should sound: strongly influenced by nature - snow, wind, and ocean - with a certain heroic impetus. This is especially true of Ithaka, essentially a concert aria of 1904. It reminds me a bit of Grieg's Landkjending, with the roll of the sea in it, but this type of genre painting probably derives ultimately from Wagner's Fliegende Holländer. The text, part of a poem by Oscar Levertin, tells of Odysseus's longing for his home country and his attempts to sail there. The poet thinly disguises a nationalist sentiment. Stenhammar's music, at any rate, makes very clear that the home country is Sweden.

The Song was Stenhammar's last major work. It has a text by Stenhammar's friend, composer and poet Ture Rangström. Stenhammar asked him to write something specifically for the work. In English, the poem comes over as claptrap, deriving its images largely from the second part of Goethe's Faust while leaving the intellect of that poem alone. It makes very little sense from sentence to sentence, even granting the poet the customary license, although one can easily enough recognize this as yet another nationalist paean. The song, of course, represents the spirit of Sweden. Rangström personifies it as a beautiful, shy girl, which would probably annoy the old Swedish raiders no end. The worst I can say about the text is that it's tainted by the Literary. Shortly after completing the cantata, Stenhammar, forced by bad health, moved into seclusion, and he died of a cerebral hemorrhage in 1927, still in his fifties. For my money, The Song is his greatest piece, even though it doesn't quite hang together stylistically. It shows an energetic, questing mind. It's full of things you expect and things you don't.

The work opens with some post-Wagnerian angst, with tropes from the Ring, as the text talks about Suffering Sweden. Actually, Rangström's passage comes across as a literary device - From Darkness to Light - rather than anything from real life. The music, however, convinces all by itself, and this happens throughout the work. About a third of the way through the first part of the cantata, there's a beautiful moment, where the music seems to suspend time (the text describes daybreak), largely given to solo soprano and women's chorus. From here to the end of the first part, we get gorgeous musical pastoralism (for me, Stenhammar's strong suit) and Stenhammar speaking for himself. The choral writing throughout is inspired and complex in a typically Late Romantic way (Mahler's Eighth and Strauss's Deutsche Motette probably represent the zenith of the style), interweaving with the orchestra, sometimes as another orchestral color, sometimes in the forefront with subtle orchestral support. The range of expression seems to continually widen, and the first part ends in a blaze.

Then comes a solemn, chorale-like "Interlude" for orchestra alone, very much indebted to Bruckner's slow movements. But it's a great example of the genre, and it's often (in Sweden) done all by itself. The second part proper opens with an unearthly, beautiful sound from the orchestra and a children's chorus (reminded me of the opening to the second part of Mahler's Eighth, without the taint of imitation), again where the music seems to be holding its breath. The soloists enter with a dancing rhythm and things liven up in a hurry. We're back to Swedish pastorale. After a darkly chromatic transition, we're into something "rich and strange": essentially, Beethoven's Ninth seen through the lens of Late Romanticism. Bits of the slow movement and the finale flit in and out, occasionally taking center stage for the instant it takes to snap your head, and then melting back into the Swedish singing and dancing. The work ends in poetic quiet.

Tellefsen and Westerberg do what they can with the Romances, except resuscitate them, but Stenhammar doesn't give them much to work with. However, the performers in Ithaka and Sången surpass the merely good. Hagegård doesn't have the most gorgeous baritone voice in the world, but he has always communicated like gangbusters. I don't even understand Swedish, but I know what he's singing about. The performers in Sången surpass even this. The work itself is incredibly difficult, both in its complexity of texture (orchestra, two choirs, four soloists, moving in and out in an intricate dance) and in its change of musical and style and mood. The choral writing, like the choral writing in Mahler's Eighth, lies beyond most large choruses. Blomstedt gets his orchestra and chorus to sound as straightforward as folk music. This is an amazing performance. Anne Sofie von Otter stands among the soloists, but it's early in her career. She doesn't stand out, although she's very good indeed. The prize goes to Iwa Sörenson, a thrillingly sweet soprano, of whom I know nothing except for what she does here. Blomstedt almost always gets the music flowing clearly. He pulls together all the threads Stenhammar has left for him. For me, he's always been a maddeningly inconsistent conductor - sometimes pedestrian, sometimes magnificent. He's magnificent here. If you're interested in Scandinavian music, this strikes me as an essential disc.

Copyright © 2003, Steve Schwartz