The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Telemann Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

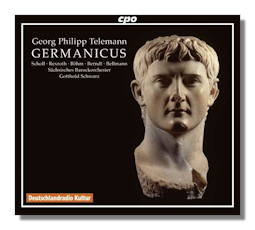

Georg Philipp Telemann

Germanicus

- Friedrich Praetorius, soprano (Caligula)

- Elisabeth Scholl, soprano (Agrippina)

- Olivia Stahn, soprano Claudia

- Matthias Rexroth, alto (Florus/Lucius)

- Albrecht Sack, tenor (Segestes)

- Tobias Berndt, bass (Arminius)

- Henryk Böhm, bass (Germanicus)

- Dieter Bellmann, speaker

Sächsiches Barokorchester/Gotthold Schwarz

CPO 777602-2 3CDs

A couple of generations ago all but the most dedicated and optimistic of Handelians would reasonably have claimed that his operas could win wide acceptance and enter the repertoire. They did. It's only within the last generation that the same has begun to happen to Vivaldi's. Could it now be the turn of Telemann? If striking recordings of the quality and flair of Gotthold Schwarz's latest offering from cpo, Germanicus continue, then maybe Yes.

Born in Magdeburg in 1681, Georg Philipp Telemann actually composed his first opera, Sigismundus at the age of 12. Forced by his family to study law and then language and science at Leipzig University in 1701, Telemann's heart nevertheless lay with music… he founded the student Collegium Musicum there which was later directed by Bach. In 1703 he became musical director of the short-lived yet innovative and stellar Leipzig Opera. It's estimated that about 75 operas were written and performed in the city between 1693 and 1720, of which almost a third may have been Telemann's, though few (identifiable as such) survive. It was during those years, though, that Telemann wrote Germanicus.

This recording reflects the incompletely known nature of Germanicus: no recitatives survive; so Michael Maul's reconstruction takes the form not only of a Singspiel with a spoken "narrative" succinctly moving forward the story of Nero Claudius Germanicus, his second campaign in Germania from 15 BCE to 19 CE as recorded by Tacitus; but also includes extracts from other Leipzig Baroque operas by Heinichen, Hoffmann, Vogler and Telemann himself. Since this amalgamation of numbers was not entirely foreign to contemporary practice, it's hardly surprising that it works well in a modern reconstruction. Particularly one done with as much attention to detail, to the dramatic integrity, and to Telemann's original intentions and relationship with the still emerging genre as this.

Nevertheless, an amalgam this decidedly is. The tests which prospective listeners/buyers of cpo's pioneering (and perhaps necessarily audacious) offering are whether it works dramatically; whether Germanicus (of which this is the only recording, of course) describes and moves forward characters and situations; whether there's enough of Telemann, whose ingenuity and creativity were still emerging; then whether the resulting music is played to a sufficiently high standard to compensate for any shortcomings of the reconstruction.

Significantly, the originality, novelty (in the best senses of the word), insight into operatic technique and impact, the beauty of many of the melodies, the dramatic force of the solo arias and duets all remain Telemann's own. And are amply presented by most of the singers and Dieter Bellmann the speaker. Germanicus himself, Henryk Böhm (bass), stands out rather more than do either Elisabeth Scholl's (soprano) Agrippina or Friedrich Praetorius's (soprano) Caligula for technique or sheer consistency and power. Under Gotthold Schwarz, the Sächsiches Barokorchester also does much more than suggest the musical aspects that tie the work together. They have very firm hands; the result is very pleasing. Woodwinds are clean and penetrating, strings full or warmth and expression. The players have a measured urgency (listen to their excellent ensemble work in an aria like Germanicus' "Gelosia" [CD.2. tr.6]) which underpins each act's structure, suggests momentum yet is rich enough in timbre to be unhurried and more than merely an atmospheric foil to the linearity of the narrative imposed by the spoken intervals, however short the latter always are. In the end, you're brought into and consequently absorbed by the story, its characters, the attendant public and personal issues examined by librettist Christine Dorothea Lachs, who was a contemporary of Telemann's. The commitment and involvement of the performers is evident from first note to last. Yet with much spirit consistent with, we can easily imagine, the ways in which such an enterprise would have been undertaken in the years before Bach arrived in Leipzig, yet apparently showed such little interest in opera.

The booklet that comes with this set of three CDs is full, informative and contains the full text in German and English. The acoustic is almost perfect… the recording was made at the Altes Theater am Jerichoer Platz in the town of Telemann's birth, in 2010. It's full and responsive without being over resonant. Every word of the principals is effortlessly clear. If you're an avid collector of Telemann's music, you'll want Germanicus, and for more than its historical or curiosity value. The same goes for those with a more general interest in the German Baroque – especially in the light of the unique place in the genre's history of Leipzig at the turn of the eighteenth century. Just as importantly, this realization of Germanicus is compelling, entertaining brings out the merits of music that, however obliquely, must play a part in raising Telemann's reputation as an opera composer.

Copyright © 2012, Mark Sealey.