The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Pettersson Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

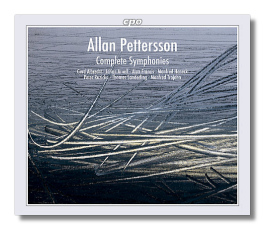

Allan Pettersson

Complete Symphonies

- Symphonic Movement 1

- Symphony #2 (1952-53) 1

- Symphony #3 (1954-55) 2

- Symphony #4 (1958-59) 2

- Symphony #5 (1060-62) 2

- Symphony #6 (1963-66) 3

- Symphony #7 (1966-67) 4

- Symphony #8 (1968-69) 5

- Symphony #9 (1970) 6

- Symphony #10 (1971-72) 7

- Symphony #11 (1973) 7

- Symphony #12 "The Dead in the Marketplace" (1973-74) 8

- Symphony #13 (1976) 1

- Symphony #14 (1978) 9

- Symphony #15 (1978) 10

- Symphony #16 (1979) 2

1 BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra/Alun Francis

2 Saar Radio Symphony Orchestra/Alun Francis

3 German Symphony Orchestra, Berlin/Manfred Trojahn

4 Hamburg State Philharmonic Orchestra/Gerd Albrecht

5 Berlin Radio Symphony Orchestra/Thomas Sanderling

6 German Symphony Orchestra, Berlin/Alun Francis

7 Hannover Radio Philharmonic Orchestra/Alun Francis

8 Swedish Radio Choir

8 Eric Ericson Chamber Choir

8 Swedish Radio Symphony Orchestra/Manfred Honeck

9 Berlin Radio Symphony Orchestra/Johan Arnell

10 German Symphony Orchestra, Berlin/Peter Ruzicka

CPO 777247-2 12CD Boxed Set 12:36

I first became familiar with the name and music of Allan Pettersson over thirty years ago from a Decca/London recording of his Seventh Symphony led by Antál Doráti, who premièred the work in 1968. That recording was dated 1972 but was apparently made in 1969 and probably released in Europe shortly afterward. In any event, I liked the piece – so did a lot of others: this was the work that gave Allan Pettersson international renown, the work that quickly became his most popular (if "popular" is a word that can be used in describing the music of this enigmatic Swedish composer). Pettersson, I'm sure, would not have been comfortable with that word. He was the ultimate outsider, a man who suffered abuse in his childhood and poor health in his adulthood (especially after the appearance of his Seventh Symphony), a composer who cared neither to please the traditionalists in music nor the avant garde.

Pettersson wanted to go his own, as it turned out, highly individual way in his compositions, and when it came to his personal misfortunes, he sought no pity and loathed those who did. He found he could vent the ever-accruing frustrations of his life of agonies through his music – music that was both decidedly unorthodox and complex. Not surprisingly, his symphonies are full of rage and tension – two qualities that permeate nearly every page of his scores. The works' structures are, at least initially, opaque in their seemingly rambling, typically one-movement designs. Moreover, the works often seem to start in the middle – try the two-movement Eighth, for example: it begins with Sibelian bassoons and probing strings that seem to reach out to the heavens, but without ever attaining them. The Sixth, near the end, almost does achieve heaven. I guess I'm struggling to describe the music of Pettersson here. His expressive language is not truly avant garde, especially for his time. Yet, it would undeniably be difficult to grasp for most listeners.

Let me attempt to give some perspective to the symphonies of Pettersson: more often than not, they seem roiling and building toward some climax, exuding a character that contains a vague mixture of Sibelius, Shostakovich (especially from his late quartets), Messiaen and Ives. Tempos seem unclear – generally the flow of the music does not come across as particularly fast or slow, but rather conflicted, tense and verging on eruption. The symphonies are typically quite lengthy: #9 and 13 are nearly seventy minutes, and several others, like the choral, politically- (and naïvely-) charged 12th, are over fifty minutes. I wish could give a brief description of each work here, but that would necessitate a word-count well into the thousands, and neither you nor I would have the time for that kind of heroism. Suffice it to say that Pettersson's music probably won't become popular in the near future, but, like Mahler's, its time may well come. The Seventh probably has the best chance at moving near the fringes of the standard repertory. But even that is not likely to occur soon.

We must thank CPO for this invaluable set: Alun Francis incisively leads most of the performances here, and overall, the orchestras respond with conviction to the various conductors. The sound on these recordings, made between 1984 and 2004, is generally good and the performances more than adequate, some utterly compelling. The booklet notes are informative and invaluable. If you're an adventurous listener, this fare could really open up new vistas for you if you aren't already familiar with the music of Allan Pettersson. Recommended.

Copyright © 2007, Robert Cummings