The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- A. Bush Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

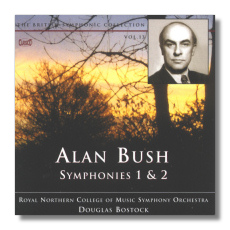

Alan Bush

The British Symphonic Collection, Volume 13

- Symphony #1 in C Major, Op. 21 (1940)

- Symphony #2 "The Nottingham", Op. 33 (1949)

Royal Northern College of Music Symphony Orchestra/Douglas Bostock

Classico CLASSCD484 71:28

Summary for the Busy Executive: One very interesting symphony, one slice of Wonder Bread, in okay performances.

Alan Bush (not to be confused with British composer Geoffrey Bush) studied composition with Frederick Corder, teacher of Bax and Bowen, at the Royal Academy of Music and privately with John Ireland. He played piano well enough to study with Benno Moiseiwitsch and Arthur Schnabel. He also attended the University of Berlin in musicology and philosophy. Always a man of the left, Bush joined the Communist Party in 1935. Unlike many of his fellows, I believe he remained a Communist throughout his life, to the detriment of his composing career. The BBC refused to broadcast his music. Many of his important premières took place in Russia and in Eastern Europe. England knew him far better as a superb teacher than as a composer. Even today, his music seldom receives a recording or even a hearing, despite the advocacy of Britten, Alwyn, Rubbra, and Vaughan Williams, among others.

Bush had a tremendous musical intellect and naturally wrote "hard" music, strongly influenced by Schoenbergian serialism, but never atonal or strictly dodecaphonic. In that respect, he found his artistic aims in conflict with his political ones. He wanted to reach "the people," but those very "the people" wouldn't have touched his idiom with a barge pole. Other politically left composers, even those outside the Soviet Union, faced the same problem: Weill, Copland, Eisler, and Blitzstein, to name a few. For a while, Bush split himself in two, writing "accessibly" for worker's ensembles and schools and hieratically in most of his abstract works. The Zhdanov decree in 1948 prompted him to take a look at his musical means. Although certainly free to do otherwise (unlike Prokofieff and Shostakovich), he nevertheless deemed his more difficult idiom an indulgence, and he set himself the task of simplifying for the masses he wanted to instruct. He continued to compose until his eyesight failed him in his 90th year.

The two symphonies (of four) show the great divide in Bush's output – up through World War II and after. I should say that I know very few of Bush's larger works, so I base my opinions more on speculation than on solid knowledge. I do strongly prefer pre-Zhdanov Bush to post-.

The Symphony #1 (1940) has an anti-Fascist program, but you needn't know it in order to appreciate the symphony. In a very crowded field of Great British Symphonies of the 30s and 40s, it stands out as one of the most powerful. It shows the influence of Schoenberg in that the composer bases the work on a series of twelve notes. Nevertheless, the series is not dodecaphonic. For one thing, Bush puts in two instances of the pitch D and never does get around to G. Furthermore, the series is almost never stated (I found only one instance of a pure statement), and the classic Schoenbergian manipulations don't apply to the series as such. The series (or bits thereof) mainly generates themes in a conventional sense. I doubt a listener used to Britten's Sinfonia da Requiem would have much trouble with Bush's First.

Containing a "prologue" plus three movements, the score is fueled by Thirties Angst. It begins as a grave lament, beautifully contrapuntal, almost Brucknerian, as if a prophet looks over the wastes of the fallen Jerusalem. The first movement proper bursts in like a looting party and proceeds its ferocious, rapacious way. It contrasts rapid, fierce passages, with fragmented, ponderous ones. Bush impresses you with how much activity he can suggest in so few notes, often in just one or two independent lines. The slow movement begins in sadness – daze in the aftermath of disaster – and then finds a broad modal tune for the violins. At times, the music rises to outcries of angry incomprehension, a long build to climactic anger, only to break off into the mood of the opening and a fragmentation of the broad tune, this time, mainly on solo violin, before one final shake of the fist.

Nevertheless, a proper leftist symphony of the time has to end in triumph. Abandoning his series for a slightly easier idiom, Bush here provides a march which seems to have taken more than a little from Shostakovich, particularly its mixture of victory and irony. It's a fine, vigorous movement, full of original touches, but not an entirely convincing ending to the symphony. It has the air of belonging to a different work. In fact, Bush extracted it in the Fifties as the standalone Defender of Peace and dedicated it to Marshall Tito. Apparently, Bush didn't perceive the irony in the score.

The Symphony #2 appeared nine years later, post-Zhdanov, and it differs from its earlier brother in ways that make me want to cry. Commissioned by the Nottingham Co-operative Society to celebrate the 500th anniversary of the founding of Nottingham, the symphony, although well written, comes across as the soundtrack to a superior travelogue. Nottingham is, of course, Robin Hood territory, so I can understand the appeal of the subject for Bush. It has four movements, the first three referring to places in Nottinghamshire: an allegro, "Sherwood Forest"; a slow movement, "Clifton Grove"; a scherzo, "Castle Rock"; a fast finale, "Goose Fair." For the most part, the symphony is "pretty" music, without any extra psychological dimension. Compared even to something as light as Britten's Young Person's Guide to the Orchestra (1945), very little holds interest. The idiom echoes many others, and one searches, usually in frustration, for something personal. The first movement consists of a "hunting" triple-time main subject sandwiching a slow procession, tinged with the Landini cadences of the early Renaissance. The second movement begins with a picture of the calm River Trent at Clifton Grove – a mood and an idiom familiar to fans of Delius.

At the scherzo, a movement of mixed meters, things look up. Bush gives us a wild, aggressive dance, much of it pulsing in fives. Naturally, there's a subtext. "Castle Rock" was a scene of proletarian protest when the resident Duke of Newcastle voted against the 1832 Reform Act. Protesters burned down the Duke's castle. The music shows more energy than anger or violence (it has less of the latter than Holst's "Mars"). Hearing this, however, recalls the pre-Zhdanov Bush. Far and away, it counts as my favorite movement of the symphony and shows up the other movements as very weak tea. The finale lets the air out again and fills much of its course with very well-crafted empty passages, superbly orchestrated.

Bostock's reading I'd call adequate, without any epiphanic moments. I can easily imagine the First Symphony done better. On the other hand, I don't expect another recording anywhere within my listening lifetime.

Copyright © 2011, Steve Schwartz.