The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Leighton Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

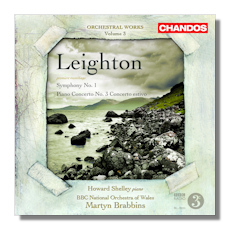

Kenneth Leighton

Orchestral Works, Volume 3

- Symphony #1, Op. 42 (1963-64)

- Piano Concerto #3 "Concerto estivo", Op. 57 (1969)

Howard Shelley, piano

BBC National Orchestra of Wales/Martyn Brabbins

Chandos CHAN10608 73:03

Summary for the Busy Executive: "I like a man whut takes his time" – Mae West.

Until recently, the British seemed unable to keep more than one living British composer in their heads at a time, although Americans have had the same trouble. However, one could characterize the English musical landscape as feudal, with one tower rising far above the rest. Elgar dominated his time, as Vaughan Williams, Walton, Britten, and Tippett did theirs, to the cost of others like Holst, Brian, Arnold, Rubbra, Lutyens, and Simpson. This began to change after World War II, as musicians and writers began to regard their own traditions as artistically inferior and increasingly looked to continental Europe for salvation. One nice thing about feudalism (maybe the only nice thing) is its sense of settled order. Postwar, so many different voices competed for attention, turf wars broke out, with one faction accusing another of Mossbackism, Triviality, or Cultivation of the Ugly. A lucky composer may have gotten a first performance but seldom a second.

Luckier than most, Kenneth Leighton's career rose "meteorically" (so say the liner notes) in the Fifties. The music was conservative and extremely strong and well-made. As time went on, however, he moved along more radical paths, including serialism. French composer Olivier Messaien proved the most lasting influence, however, and in his later music Leighton achieved a personal synthesis of all his different styles. However, he never had a "hit," on the order of Walton's Façade, Vaughan Williams's Lark Ascending, and certainly not Holst's Planets. Furthermore, like Holst, he preferred to stay out of the spotlight. Consequently, while he had the deep respect of his peers and continued to receive commissions, he faded somewhat from public consciousness after his too-early death from cancer at 59. Following the up-and-coming, very few labels rushed to record his work, which also heaped oblivion upon him.

Fortunately, the enterprising Chandos has taken up his cause with a series of CDs, and we (especially in the United States) get to hear what the fuss was about. He certainly deserved the fuss. Both the symphony and the concerto operate at the architectural level of a Robert Simpson – major statements based on a radical brevity of structural components. Obviously, Leighton mastered variation technique, but he impresses even more as a shaper of symphonic narrative.

Leighton made two abortive tries at his first symphony before he found his way, since took the symphony as a form very seriously indeed. His three symphonies lie roughly ten years apart from one another. The First comes out of the Walton Wing of British music, but it speaks with a new, greater intensity than Walton's followers usually do. As I say, I find major affinities, not least in intellectual focus and force, with Simpson's symphonies. Both men interest themselves with complex counterpoint, although Simpson gravitates toward "learned" counterpoint and Leighton's seems more "organic." Leighton has stripped down his basic materials to about two main themes, varied throughout all its three movements. Furthermore, this is no mere exercise in pattern-manipulation, but an argument of huge span that grips the listener from first measure to last. Overall, the score resides in an austere, even dour neighborhood. The first movement grows intensively from a single thread to a maestoso climax leading directly to the scherzo, which the composer stated "loosens the reins, and in a spirit of rebellion seeks to arrive at an affirmative answer by sheer force of will." This is no hale Beethovenian scherzo, however. It emphasizes protest and force, reminding me somewhat of the scherzo in Vaughan Williams's Fourth, and one can debate how affirmative Leighton's answer. It comes across to me as angry, obsessional (mostly due to the sparseness of the material), and desperate.

The finale begins with a rhetorical regroup, a scaling-back of forces. The first section declaims a new beginning, but it's a difficult one. Much of it consists of two lines very close together – half-steps, whole steps, here and there a minor third – and the effect is that of a screw tightening. As more voices gradually join in, the music begins to relax, although it never loses its worry. About halfway in, we even get some genuine cantabile. The music laments its way to an emotional highpoint, which I hear as some sort of jeremiad. This symphony doesn't weep for an individual, but for a civilization, another Age of Anxiety. Since Beethoven upped the stakes in the symphonic finale from entertainment to enlightenment, composers have had trouble finding some sort of resolution in their work. The music quickly winds down to two flutes and a pizzicato bass, ending the symphony in the middle of nothing. Some may find that unsatisfying, but not me. I believe it the only resolution possible, given what happens before.

Leighton lived long in England's North. He also taught at the University of Edinburgh. Oxford, however, appointed him to succeed Edmund Rubbra. Apparently, the comparatively warm weather – and it's only comparatively warm in the south of England – inspired him to write his Piano Concerto #3, "Concerto estivo" (summer concerto). The composer describes it as more "lyrical" than his first two, by which he seems to point to a less severe contrapuntal texture, but the concerto lies far from the pastoral implications of a summer day, even with a slow movement titled "Pastoral." If anything, Leighton has pruned his material even further than in the symphony. We don't get anything so mundane as a theme. Instead, Leighton derives his material from a chord and a small kit of intervals – rather Spartan. Actually, like Britten's "Lachrymae," the concerto goes through its three movements (fast-slow-fast) working up to the full statement of its theme as the score's apotheosis. The psychological skies aren't as dark as in the symphony, but they're by no means sunny. The first movement starts slowly by playing around with intervals until it breaks into a driving toccata. The second mostly flirts with stasis until interrupted by another toccata section (and the transition from one to the other is masterly). It breaks down into torpor again and we arrive without pause at the finale, a set of variations. Remember, there's no real theme here; the movement works toward revealing one through variation – a pretty audacious move. Fast sections frame the central slow one. After a full cadenza, we finally get the expression of the Ur-theme, which turns out to be the concerto's opening, regularized. An exciting coda, and we're out.

No orchestra would regard either score as a walk in the park. Brabbins and his Welsh players have the measure of both, with crisp rhythms, clear textures, a sure grasp of structure, and emotional commitment. Howard Shelley is an excellent soloist, negotiating the muscularity of Leighton's piano writing (Leighton was a virtuoso himself) and delivering from the score that grand Romantic intellectualism characteristic of Brahms as well. I love both Brabbins's and Shelley's work here, a composer's champions at a level seldom encountered. After all, one can't call Leighton a known quantity or the performing tradition deep and robust. That they have spent so much effort on someone who rewards it just warms me up.

Copyright © 2014, Steve Schwartz