The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Walton Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

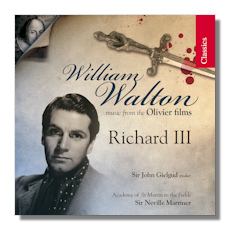

William Walton

Music from the Olivier Films

Arranged by Christopher Palmer

- Richard III: A Shakespeare Scenario *

- Fanfare and March from Macbeth

- Major Barbara: A Shavian Sequence

* Sir John Gielgud, speaker

Academy of St. Martin-in-the-Fields/Sir Neville Marriner

Chandos CHAN10435X 60:45

Summary for the Busy Executive: "Sound drums and trumpets."

The British composer William Walton began writing film scores in the early Thirties with music for Escape Me Never (1934). The music often outshone the movie and certainly ran steps beyond most of the British and Hollywood work of the time. However, Walton, while certainly capable, didn't achieve his present status as one of the greatest film composers of all until his collaboration with Lawrence Olivier on three Shakespeare films: Henry V (1944), Hamlet (1948), and Richard III (1955). By that time, Walton had learned several lessons – as had just about every other film composer – from the example of Prokofiev's Alexander Nevsky (1938), including how to give essentially snippets of music symphonic weight and movement. The Henry V score alone forced a major reassessment of Walton's previous film efforts.

Other than excerpts, usually confined to three or four arrangements by Muir Mathieson, this music has to my dismay and shock been unavailable for many years. Chandos, perhaps as part of its Walton Edition, has begun to make up for the long absence by releasing the Shakespearian scores, along with other Walton film music. The late Christopher Palmer, a film fanatic and fortunately a superb musician, arranged Walton's cues into coherent movements, although he admits that Walton's practice in Richard had been to write in long paragraphs, so the job became relatively easy. We get, probably for the first time outside of seeing the movie itself, almost everything in Walton's cues, rather than the drastically-reduced, though highly effective suites made by Mathieson.

Richard III represents Walton at his best – a revving Rolls-Royce engine of invention and drama. The tunes are unbelievably good, and of course Walton's craftsmanship provides elegantly perfect settings for these jewels. I admire Walton's other work, but I really love these – the creation of a mock-Tudor style that owes nothing to either Edward German or Vaughan Williams, the glitter of the orchestra, and of course the themes that hug you.

The Macbeth pastiche comes from incidental music for a Gielgud 1941 production of the play. The musical material comes mainly from the banqueting scenes and "March of the Eight Kings." By throwing in a cartload of double reeds, Walton gets the effect of bagpipes. As Palmer remarks in his liner notes, "the more flutes and piccolos and oboes and cors anglais available, the better."

Also from 1941, the composer's score to the Shaw-Pascal film Major Barbara rambles through familiar Old Waltonian grounds. Cheeky, subtly satirical (the opening credits transform "Onward, Christian Soldiers" into a not-quite pompous fanfare and march), it bubbles with good humor, and it boasts a chameleon love theme that expresses everything from light courtship to Tristan-like passion. My favorite section of the score, Adolphus's visit to Undershaft's factory, bangs and clatters with drums, hammers, and anvils while remaining purposeful and cleanly orchestrated.

I'm used to the old Walton EMI recordings of the Shakespeare suites, so Marriner came as a bit of a surprise, particularly his tempos. Walton I'd call an "efficient" conductor, one who lets the music pretty much stand on its own. Marriner is more thoughtful and deliberate. Early on, I had the queasy feeling that he adopted a slower-than-what-I've-heard beat just to gin up Significance, the last thing this music needs. However, I always found a very musical (and effective) reason for his deviations from what I expected. I will say, however, that Chandos's engineering seemed to me less clear, though more natural, than the EMI recording. You say "potato." It's not enough to keep anybody away from this magnificent work.

Copyright © 2009, Steve Schwartz