The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Rubbra Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

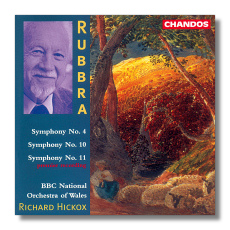

Edmund Rubbra

- Symphony #4, Op. 53

- Symphony #10 "Sinfonia da camera," Op. 145

- Symphony #11, Op. 153

BBC National Orchestra of Wales/Richard Hickox

Chandos CHAN9401 58:22

Summary for the Busy Executive: Three stunners.

Rubbra wrote much of his fourth symphony while serving in the army during World War II. I have no idea how he found the time, but the piece shows no sign of rush. It remains, in fact, one of his most powerful and tautly-argued symphonies. The work begins oddly, in that Rubbra doesn't open with a "grabber," but with a lovely idea composed of a downward fifth plus an upward third (major or minor). Sometimes he even chains occurrences together - eg, G-C-Eb-(Eb-)Ab-C. It sounds more like a slow movement throughout most of its course, but a rhythmic motive (2 sixteenths to a tied eighth), introduced shortly after the opening, becomes the subtle means of increasing rhythmic excitement, until suddenly you find yourself in the middle of intense activity. The music climaxes about four minutes before the end and winds down in a coda similar to the opening. The movement spans large tracts of time - it lasts about thirteen minutes - and, as usual with Rubbra, there is no sonata-allegro structure. Don't waste time trying to hear first and second subjects. One idea gets varied, and then the resulting mutant becomes subject to change. The ideas consequently interlock, rather than, as in a Mozart symphony, fall into place. In addition, Rubbra has a strong rhetorical sense, so that the movement impresses as an inexorable march forward, rather than as a conversation among principals.

Rubbra conceived of the second movement as a "breather" between the first and the last. It functions like (and sounds a modern equivalent of) Brahms' symphonic intermezzi - tender, gracious, but not lightweight. Nevertheless, its five minutes doesn't run down usual paths. In fact, it exemplifies Rubbra's "continuous variation" method on a smaller scale. You can almost see the main idea changing from one sounding to the next. Here, Rubbra works with two ideas – one involving a rising and falling third and the main idea of the first movement rhythmically disguised.

The final movement splits into two large sections: an introduction and march. The introduction broods on yet another disguised version of the opening movement's main idea, here split up between sections. He also works up a singing passage, using the main accompanying figure to the first movement. The allegro begins boldly, with yet another variant on our old friend, the falling fifth-rising third, this time on horns and strings. In character, it reminds me of the finale of Brahms' first - that kind of heroic tone. Of course, heroism differs from Brahms' time to our own. Rubbra's movement has as much sorrow as strength in it, and joy wins out only at the very end. Ideas from the other movements flit in and out, but the overall effect is that, in hindsight, the symphony "feels" monothematic. I can't really confirm this without a score, however. At any rate, Rubbra works toward a climactic chorale, mostly through beautifully independent three-part counterpoint. But this is a chorale only in tone, since it too is composed of three independent strands. It's just that the rhythmic values have gotten larger. Robert Saxton's liner notes point out that the main strand comes from an accompanying figure in the first movement, but it's just as true to say that it's simply another exploration within the compass of a fifth - in other words, a variant of what we have seen as a ruling idea. In either case, the organization across movements is nothing less than masterful.

Rubbra wrote his tenth symphony in his seventies. Saxton sees affinities with the Sibelius seventh. Both works play extensively with scalar motives. Both are in one movement. However, Rubbra's practice of constant transformation and little, if any, traditional development or reliance on classical forms takes this symphony out of Sibelian territory, as does the emphasis on intricate counterpoint. Furthermore, although the symphony has several sections, one tends to find oneself in the middle of a new section, rather than have a sense of arrival - which means that Rubbra pulls you through the piece by other-than-classical means. The work is even more compact than the fourth. Remarkable moments go by in a blink, including a raptly beautiful couple of measures given to solo violin in the second "Lento." Throughout most of the work, a restless feeling dominates, with little or no sense of balance or arrival. Yet, by the (extremely brief) coda, serenity comes. I have no idea how Rubbra pulls it off.

The composer dedicated his eleventh symphony (1980) to his second wife, Colette. In one movement, it divides into two major sections, played without pause. It's his final essay in the form and his last major orchestral work. Rubbra confounds at least my expectations, since he comes up with neither a love poem to his wife nor a grand summing-up of the cycle. I doubt he knew at the time it was to be his last symphony, and he did live six more years. If anything, it's a spiritually exploratory work, in the same way as Vaughan Williams' sixth, although more concentrated. The ties between the two become even more apparent when the symphony takes up a prominent snare-drum rhythm from the Vaughan Williams piece. The tempo indications – "andante moderato" and "adagio: calmo e sereno" - mislead. This music scarcely rests. Even in moments of quiet, something unsettling - inconclusive harmonies; queasily-conflicting rhythms; quick, nervous switches of key - happens. Whatever triumph or serenity the symphony attains comes in the last minute, with a glorious sound, dominated by brass, melting into a C-major chord, laid out in such a way as to hint at the music's going on "toward the unknown region." The piece doesn't end, so much as we leave it at this point. It differs from the inconclusive ending to Vaughan Williams' sixth in its tone. Vaughan Williams' work disturbs far more. Vaughan Williams seems to look into an abyss and has the stoic strength to accept Nothing at All as an answer. In Rubbra, no matter how agitated the music gets, one senses a ever-present spiritual grounding, a sense of reasonable expectation that some healing answer will come.

Of course, to even begin to talk this way about a piece of music, one must deal with a work in which the musical matter - if not its emotional import - is clear, and that means a tremendous amount of craft from the composer. Rubbra builds from three ideas, all stated at the very beginning in a duet between horn and harp, and strings: a rising and falling fifth; various sequences of notes within a minor third; a singing line beginning with an upward minor sixth and falling more or less scalewise. The rising and falling fifth not only furnishes arresting themes and climaxes, it also provides accompanying figures. The orchestration is almost preternaturally clear, spectacularly so in a quiet way after the first big climax, when winds, celesta, and strings take up three rhythmically-independent strands. Most of the symphony trades in spare textures, often just two voices over a pedal tone. To some extent, Rubbra derives his form from his tenth symphony, in that both are single movements lasting about a quarter of an hour. Here, however, the argument is even more tightly-knit. You can't really divide this movement into subsections as easily as the tenth. You apprehend it as one huge span with a very short coda. Rubbra does this throughout his career, of course, but this symphony does seem the most extreme example, without descending into a superficially bizarre idiom. This seems the essence of Rubbra the symphonist.

Hickox and the BBC National Orchestra of Wales in my opinion give definitive performances of these emotionally and structurally complex works. In fact, the entire cycle is superbly well played, beating out the old Lyrita recordings with Handley and Del Mar. The Barbirolli fifth fails in the orchestral playing. Furthermore, it's the first (and for a while probably the only) complete cycle of these magnificent works. Hickox has become the current best interpreter of a large spectrum of modern British music. Chandos sound is its usual excellent. If Rubbra's your cup of Ovaltine, lose any hesitation.

Copyright © 1999, Steve Schwartz