The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Alwyn Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

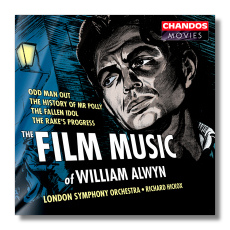

William Alwyn

Film Music

- Odd Man Out Suite

- The History of Mr. Polly Suite

- The Fallen Idol Suite

- The Rake's Progress - Calypso

London Symphony Orchestra/Richard Hickox

Chandos CHAN9243

Twentieth-century British music has distinguished itself in the production and variety of great stylists who also knew the craft of composition: Elgar, Vaughan Williams, Holst, Brian, Walton, Britten, Tippett, and Davies lead a very long list. Not only do you get the pleasures of music well-made, but you can generally identify the maker after a few bars, which, to some extent, adds to the pleasure – the reinforcement of the idea that the music comes from an individual artisan, not from off the rack.

However, although originality counts for much, it's not everything, as a composer like Berlioz sometimes proves. The music can be original, but awkward and uninvolving at the same time. At any rate, we generally mean by originality that inspiration applies to the creation of a new idiom. Yet, a composer may be original in many ways, not the least of which is how he uses an idiom already received. Schubert, for example, takes the language of late Haydn and then Beethoven, clumsily at first, then with increasing mastery, until by his late period he has found a personal, "associative" approach to sonata form. This kind of originality is especially true of the so-called "lost generation" of British composers: Rubbra, Arnold, Rawsthorne, Jacob, Benjamin, Bax, Lloyd, Simpson, and William Alwyn.

The British "lost" this generation in one of their periodic attacks of remorse over their insularity. The British, of course, are probably among the most musically cosmopolitan on the planet, as an examination of concert schedules, radio programs, and recordings would amply prove. The BBC, perhaps the most influential disseminator of music in the country, in effect ignored their works in favor of those deemed more "with it" – primarily post-Webernian serialists, in keeping with the international climate. For some reason, Britten was still played and Tippett had moved from a Hindemithian neo-classicism to a personal synthesis of jazz, Hindemith, Stravinsky, late Beethoven, and a fascination with musical simultaneities. However, I should note here an idea originating thirty years ago with one of my professors (a committed serialist, by the way) – namely, that there is a deep vein of traditionalism in most British composers, no matter what their idiom. Perhaps it's due to their very thorough training or to the sources of commissions (churches, schools, festivals, theaters, and so on – all with a strong social and public component – as opposed to contemporary specialist organizations, universities, and government radio).

Those left behind were primarily symphonists and, as such, committed to tonality and traditional notions of phrasing. Of these, the Rubbra, Alwyn, Rawsthorne, Arnold, and Simpson stand out, with magnificent symphonic series. Again, I can find a distinctive idiom in none of them (it would be hard to play drop-the-needle with these folks), but each has an individual viewpoint to symphonic construction and materials. Alwyn, in fact, has written five symphonies, each one with a different approach to symphonic form. Chandos – as it has done for Parry, Stanford, Vaughan Williams, Moeran, Walton, and Rubbra – seems bent on giving us the meat of Alwyn's catalogue, having recorded all the symphonies, some concerti, songs, and chamber music.

Alwyn was very much the polymath – a virtuoso flutist, a strong painter deriving from Cezanne, a fine essayist, and a prize-winning translator of modern French poetry, as well as a composer and effective administrator. He scored many documentaries and some of the best British films of the 40s, but generally viewed his movie work as a paid chance to "practice" orchestration to improve his concert works. He was far too hard on himself. In fact, the main problem with Alwyn's film music (the Max Steinerish Wagnerian subcommentary aside, which he falls back on in the longer sequences) is that the ideas are a little too big: you want to hear further development, as in a symphonic movement. Both the "Prélude" and "Police Chase" sequences of Odd Man Out suffer from this.

The History of Mr. Polly, on the other hand, shows Alwyn's genuine gift for comedy, to some extent a matter of witty and vulgar quotation – for example, in "Wedding and Funeral" he raises Mendelssohn's wedding march to Elgarian splendor at the wedding of Mr. Polly, a draper's assistant, to an ambitious termagant and later plunges it into Chopinesque funerea at the funeral of Mr. Polly's father. In "Murder Arsonical" (where Mr. Polly sets fire to his shop, so that a faked suicide can allow him to escape his wife), bits of Wagner's Magic Fire music keep threatening to break out, while the entire section ends with a boozy quote of "The Bear Went over the Mountain." Also a genuine charmer worth mention is the high-spirited little fugue of the "Punting Scene," scored with almost elfin delicacy. For me, this is Alwyn's most effective film score.

Both the public and film insiders acclaimed Alwyn's music for The Fallen Idol, but while highly effective in the film, the music is far too closely tied to action and image (in fact, in many places it makes most of the film's emotional impact) to stand well on its own. Unlike, say, Walton's set pieces for Henry V or even Alwyn's score for Odd Man Out, there's little musical logic in the sections. It makes its mark in the film, but I don't particularly care to hear it in concert form.

Incidentally, much of Alwyn's (and Walton's) film music was lost by Pinewood Studios. Mary Alwyn, the composer's widow, found some scores and sketches while cleaning out her attic. The major job of putting them into coherent suites fell to the late Christopher Palmer, an ardent and supremely gifted champion of film composers, as a scholar, polemicist, and compositeur, restorer, and stitcher-together of soundtrack scraps. Whenever I saw his name on an album or CD, my heart skipped a bit at the thought of the wonderful present I was about to give myself. I will miss him.

Hickox and the London Symphony do very well, and the sound is Chandos' usual superbly spacious.

Copyright © 1996, Steve Schwartz