The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Weinberg Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

SACD Review

SACD Review

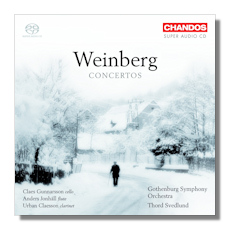

Mieczysław Weinberg

Concertos

- Fantasia for Cello & Orchestra, Op. 52 1

- Concerto [#1] for Flute & String Orchestra, Op. 75 2

- Concerto #2 for Flute & Orchestra, Op. 148 2

- Concerto for Clarinet & String Orchestra, Op. 104 3

1 Claes Gunnarsson, cello

2 Anders Jonhäll, flute

3 Urban Claesson, clarinet

Gothenburg Symphony Orchestra/Thord Svedlund

Chandos CHSA5064 Hybrid Multichannel SACD 79:25

The eventful career of Mieczysław Weinberg is mirrored by confusion over his proper name. For years, he was commonly known as Moisei Vainberg. This is because he left his native Poland at the start of World War Two and came to the Soviet Union. (His family remained in Poland and eventually was killed in a German-run concentration camp.) There he had some success as a composer – and a collegial relationship with Shostakovich – but his Jewish faith made him a target for Soviet scrutiny. In fact, he was arrested in 1953, and survived in part due to Shostakovich's intervention, and in part because Stalin himself died not long after. Weinberg then enjoyed greater security and stature in the Soviet Union, and he amassed an impressive catalog of works until his death in 1996. Since then, the West has taken a closer look at his life and music, and writers are increasingly reverting to the more typically Polish spelling of "Weinberg" (actually "Wajnberg").

Many of Weinberg's works were recorded by the Russian Melodiya label, but two of these concertos – the Clarinet Concerto and the Second Flute Concerto – are receiving their first recordings here. The almost ascetic Clarinet Concerto (1970) is remarkable for how much it sounds like the work of Carl Nielsen, of all people. The composer's emotions are kept reined in here, but one senses a great deal of tension just below the surface. The Second Flute Concerto (1987) is a more engaging work, and its last movement includes famous snippets from the flute repertory, including bits of the "Badinerie" from Bach's Second Orchestral Suite, and Gluck's "Dance of the Blessed Spirits" from Orfeo ed Euridice.

The two other concertos are stronger, though, and one can understand why they have been recorded previously. The Cello Fantasia (1951-53) is in an arch-like single movement, with the arch defined by terraced increases and decreases in tempo. Many of the melodies suggest Jewish folk origins, although they could as easily be original to the composer. The First Flute Concerto (1961) boasts a short yet tremendous, dark, and very Shostakovich-like slow movement.

All three soloists are principal members of the Gothenburg (Göteborg) Symphony Orchestra, a fine Swedish orchestra now over a century old. Gunnarsson, Jonhäll, and Claesson do the orchestra's reputation justice with performances that are polished and that seem to get to the core of the music's meaning. Conductor Svedlund is a violinist with the orchestra, but he also has a career as a conductor. Standing in front of the orchestra rather than sitting within it, he knows what he wants the musicians to say, and knows how to get them to say it. David Fanning's booklet notes are predictably fine, and the recording (made in 2005 in Gothenburg's main concert hall) is excellent.

Copyright © 2009, Raymond Tuttle