The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Handel Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

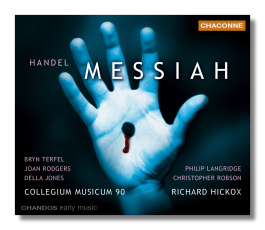

George Frideric Handel

Messiah, HWV 56

Joan Rodgers, soprano

Della Jones, mezzo-soprano

Christopher Robson, counter-tenor

Philip Langridge, tenor

Bryn Terfel, bass-baritone

Collegium Musicum 90/Richard Hickox

Chandos CHAN0522 2CDs 140:51

Summary for the Busy Executive: Elegant.

As you read this, someone, somewhere in the world, is probably performing something from Handel's oratorio Messiah. Messiah rates not only as Handel's most popular oratorio, but as the most popular oratorio ever. People who have never heard the entire thing can sing the "Hallelujah" chorus and in parts, to boot. That, of course, is the megahit from the work, but one does have to suffer from the pickies in order to find any weak number in this score.

As for recordings, you have a heap to choose from: McGegan's scholarly "complete" edition to Beecham's wretchedly excessive, insanely wonderful Berliozian extravaganza. One can pick a recording for the voices (Klemperer's Schwarzkopf, Grace Hoffman, Gedda, Hines; Ormandy's Farrell, Martha Lipton, Davis Cunningham, Warfield; Mackerras's Elizabeth Harwood, Paul Esswood, Janet Baker, Robert Tear, and Raimund Herincx). If a choral fanatic, take a look at William Christie's Les Arts Florissants, Harry Christopher's Sixteen, John Eliot Gardiner's Monteverdi Choir, Shaw's Robert Shaw Chorale. You can pick a "traditional" Messiah like Malcolm Sargent's mighty Huddersfield Choral Society (a sentimental favorite of mine). You can even choose, God save us all, a pop Messiah with Chaka Khan, Gladys Knight, Roger Daltrey, Jeffrey Osborne, and the Visual Ministry Gospel Choir (haven't heard it, but it sounds wild).

Then there are what I call the "baseline" Messiahs. Modern vs. HIP doesn't matter to me, as long as the conductor doesn't ride his hobby horse to the extremes of either pedantic scholarship or vulgar "re-creation." One needs fine soloists, but also a great chorus, since the chorus carries the burden of so many of the "flash" numbers, particularly in the first part. I would also insist on selecting the traditional movements (no triple-time "Rejoice greatly," for example; the duple-time syncopated version instead; no versions reproducing a particular performance in Handel's lifetime). If you were to recommend a Messiah recording to someone who never heard it before, you'd likely pick one of these. I'd put Colin Davis's Sixties version, McGegan's absolutely complete version, and even Boult's recording with Sutherland in that category.

The late Richard Hickox fits neatly in here, even though, let's say fifty years ago, people would have considered this recording radical. He leads a reduced orchestra with players steeped in Baroque performance and at least one period instrument (or a modern copy): the natural trumpet. Furthermore, he uses a standard performing edition.

The five soloists constitute one of the best I've heard. Only Bryn Terfel, however, possesses a particularly arresting voice, though he's the worst singer in the lot. Still, he's not terrible. He has only begun to indulge in the hokey operatic scoops, slides, and aspirations that marred his recital of English songs. He proves that, when he puts his mind to it, he can actually hit a note straight on. However, he's a bit stiff, compared to the others. All of them have not only superb breath control but also a musical intelligence that subtly phrases according to textual meaning. Joan Rodgers and Philip Langridge in particular seem to stretch out their lines forever without needing a breath. My one nit concerns the inclusion of both counter-tenor Christopher Robson and mezzo Della Jones. Why, when one or the other would do? Surely, I don't complain about the performance of either one. It just seems to me coals to Newcastle.

The choir soars just as high as the soloists – a good thing, too, since the choruses count among the glories of the work. The melismatic choruses (eg, "And He shall purify") with their long runs of quick notes on a single syllable actually derive from Italian duets by Handel. Two solo voices are far more flexible than two choral sections. For one thing, one runs into synchronization problems. Furthermore, choirs strip their throats and punish their diaphragms trying to get through those parts of the oratorio. Hickox's choral singers not only synchronize, they take the passages at a fast clip and with ease, even the heavier voices of altos and basses. Furthermore, they're not killing themselves just to get out the notes, but they phrase as beautifully as the soloists. Every line has its own shape, which you can hear within their wondrously clean ensemble. In fact, they seem like an extension of the string section – alert, athletic, and suave as hell.

The period orchestra is immaculate. No surprise – its leader is violinist Simon Standage, and a few other well-known players of early music pop up as well. The refiner's fire dances lightly and gracefully. The approach of the heavenly host lights up the skies to announce the baby's birth. The stylish Crispian Steele-Perkins sounds the heroic trumpet.

Hickox was my favorite interpreter of British music after Adrian Boult. He died way too young. Here, he shows his command of Handel. He creates drama within a restricted dynamic range, by a mastery of crescendo and diminuendo and an insistence on clarity. Everything has shape. It's close to Pinnock's interpretation (another favorite). But where Pinnock enjoys the nervous energy of the score, Hickox emphasizes its grace and sophistication without burying its power. Colin Davis used to be my go-to recommendation for those new to the work, but its appeal has bleached out for me over the years. Hickox has replaced him.

Copyright © 2010, Steve Schwartz.