The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

-

Alain Reviews

Berg Reviews

Blackwood Reviews

Copland Reviews

Ives Reviews

Nielsen Reviews

Prokofieff Reviews

Stravinsky Reviews - Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

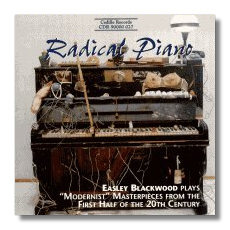

Radical Piano

Modernist Masterpieces

from the First Half of the 20th Century

- Serge Prokofieff: Sarcasms

- Igor Stravinsky: Sonata (1924)

- Easley Blackwood: Ten Experimental Pieces in Rhythm and Harmony

- Alban Berg: Sonata

- Carl Nielsen: Three Pieces, Op. 59

- Jehan Alain: Dans le reve laisse par la ballade des pendus de Villon

- Charles Ives: Study 20

- Aaron Copland: Piano Variations

Easley Blackwood, piano

Cedille Records CDR90000027 75min

I've never quite understood why piano music from the 20th century (Ravel and Debussy excepted) hasn't gained a foothold in concert programs. There's certainly a lot of it, from all wings, and from composers whose orchestral music appears regularly. Even including student recitals, I've never heard the Stravinsky Sonata or Serenade, the Bartók Sonata, or any Prokofieff sonata other than the seventh from a concert-hall seat. My acquaintance with the repertoire comes almost exclusively from recordings, ever since the RCA Horowitz Collection LP, with electrifying performances of Scriabin, Prokofieff, and Barber. So if nothing else, full marks for the program here, but fortunately the disc offers much more than that.

For about fifty years, Easley Blackwood has proven himself again and again a musician of intelligence and taste. He gets inside each piece here – from the in-your-face Sarcasms to the poetic Dans le reve. The Prokofieff comes from the still-early days of modernism, and Blackwood manages to convey the excitement of new discoveries, sonorities, and indeed a new music. Stravinsky's Sonata, one of the great examples of the genre, shows a desire for mastery rather than for surprise, although the piece has them in spades. Blackwood doesn't make the typical mistake of "objectivity," depriving the music of its wit and, in the words of Blackwood himself, "subtle tenderness." Above all, he doesn't lose the forward propulsion of the music. The notes may be staccato, but there's a larger rhythmic pulse in all of Stravinsky's music. Blackwood has mastered the trick of finding it.

I admit to liking Berg the least of the Vienna Three, and the Op. 1 Sonata has never been a favorite. I find it stuck in the early Schoenberg tonal-chromatic idiom, which always strikes me as late 19th-century noodling around. In a sense, the Berg Sonata is young man's music, with one rush to climax after another. Blackwood, however, manages to shape the piece, so that at least he has somewhere to go if he needs to get louder. Under his fingers, the work becomes more meditative than thrill-seeking, and the contrapuntal strands that compose the texture become distinct. Blackwood's own Ten Experimental Pieces are also, I find, typical of young men's music, and not just because I know he composed them at fifteen. Their relentless seriousness or, rather, their desire to be taken seriously I think marks them. Still, they are impressive works for a composer of any age. In his liner notes, Blackwood writes that he finds unintentional humor in them, but if so, the jokes have mostly flown by me. Perhaps it's the older composer looking back indulgently at his younger self. Nevertheless, these pieces need no apology. They show a strong, directly communicative, and individual voice.

The Nielsen comes from the composer's final period, and much of it sounds a bit like the nearly-contemporary clarinet concerto. The pieces can easily elude the listener, especially with their abrupt mood swings and wide emotional range. Blackwood manages to keep things together, and in the second-movement Adagio, produces real poetry.

Although known primarily for his organ music, Alain did manage a few works for other instruments. This piece, inspired by Villon's "Ballade of the Hanged Men," is one of those long French adagios, kin to Messiaen's "Louange e l'Eternite de Jesus" from Quatuor pour la Fin du Temps, which challenge performers to extend the line out past all expectation. This Blackwood does astonishingly well, even as he also builds a long dynamic arch.

The Ives study is another phantasmagoria, along the lines of the "Concord" Sonata's "Hawthorne" scherzo, but without the latter's cohesion. Unlike other Ives piano studies, it really does seem like a record of experiment with new piano styles. Blackwood plays cleanly, and in the final minute manages to pull something coherent out of the bubbling pot, but I find the work itself pretty much of a mess.

Blackwood recovers brilliantly, however, with a stunning rendition of Copland's Piano Variations. Its strength comes mainly from the excitement Blackwood generates, particularly in the rapid-fire jazzy sections of the work – runs cleanly tossed out – as well as from the sense of architecture Blackwood conveys. This is one account of the Variations where you can actually tell when you've arrived at a new section. It doesn't run together like underdone eggs.

The sound tries to emulate a room rather than a studio or hall, in short, perfect for the music.

Copyright © 1996, Steve Schwartz