The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Schulhoff Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

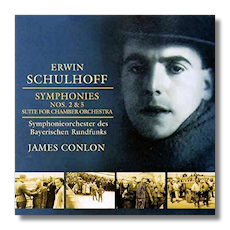

Ervín Schulhoff

- Symphony #2 (1932)

- Symphony #5 "A Romain Rolland" (1938/39)

- Suite for Chamber Orchestra, Op. 37 (1921)

Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra/James Conlon

Capriccio 67080 72:46

Summary for the Busy Executive: More tragedy from the last 100 years.

Ervín Schulhoff, a Czech Jew imprisoned by the Nazis (he died in the Wülzburg concentration camp on 18 August 1942 from tuberculosis), wrote music like birds sing. He began as a piano prodigy, getting into the Prague conservatory on the recommendation of Dvořák himself. Schulhoff's career divides neatly into early, middle, and late. Early on, he gets caught up in various currents of the Twenties: the fascination with jazz, neoclassicism, dada, and even some expressionism. Georg Grosz became an artistic hero, and Schulhoff had one of the largest private collections of American jazz records in Europe. His middle period is largely neoclassic, while his final one connects both to the German neue Saechlichkeit and to Stalin's Socialist Realism.

This CD brings together music from all phases of Schulhoff's career. The earliest, the Suite for Chamber Orchestra, presents stylizations of jazz popular dances, taking off from pieces like Stravinsky's Ragtime. Four years later, Schulhoff recycled this music for his ballet Die Mondsuechtige. Given Schulhoff's knowledge of real jazz (not always the case among the European composers who wrote jazzy pieces), I expected an individual or at least unusual take, but the music doesn't differ all that much from something like Martinů's Revue de cuisine or Le Jazz. Still, it's a very witty piece. The most unconventional movement in the suite is "Step" (that is, the bare-bones music played for a tap dancer's "break") – all percussion. However, if you've ever heard what a jazz drummer does with his kit for a tap dancer, you might find it a bit tame. For me the most affecting movement is the "Tango," sinuous, uneasy – music you might hear in the Twilight Zone. The scoring throughout is very light.

Schulhoff worked for many years for radio, as conductor, composer, and pianist. As a composer, he viewed his main problem as effective orchestration overcoming the crummy fidelity. The usual gambits of soulful, Brucknerian massed strings sounded muddy and "small" at the same time. The limits of radio moved him into neoclassicism – clear, vigorous counterpoint, light strings, and an emphasis on the reedier, more penetrating winds, like oboes and high flutes. The Symphony #2 – to judge by the number of recordings, his most popular – represents the summit of this phase. In four movements, the symphony begins with a motor-allegro, filled with little Baroque licks. The following andante con moto, emphasizes the "con moto" rather than the andante. It brings to mind a pokey gavotte. Again, the Baroque, objectified and updated, shows up here and there in turns of phrase and harmony. It's more a matter of suggestion than imitation. The scherzo reverts to Schulhoff's early jazz manner, with solos for muted trumpet and sax, a greater emphasis on percussion and syncopation, and strums from the ol' banjo. Despite the previous movements, it doesn't seem out of place – my favorite of the four. The finale lets its hair down in a Haydnesque rondo. Obviously, Schulhoff has little interest in the Grand Statement. The symphony charms, rather than exhorts or lectures. If you enjoy Haydn symphonies, you might go for this one.

However, Schulhoff's musical mind had trouble settling on any one thing. In the early Thirties, he committed himself to Communism and, like most artists on the left, wondered about how his art could uplift the proletariat and convert the bourgeoisie. Many composers with Schulhoff's predicament based their art on popular, vernacular sources, Copland and Weill among them. Schulhoff, of course, could easily and logically have reverted to his jazz manner, but I believe his artistic restlessness denied him that possibility. His music became more outwardly serious and dour, in a way that reminds me both of Weill's first symphony (also with a high-minded social program) and of Shostakovich's "poster" symphonies. His fourth symphony addressed the Loyalist cause of the Spanish Civil War, and his fifth, the Munich Agreement which effectively left Czechoslovakia to the Nazis.

Schulhoff's dedication of the fifth to French Nobel laureate Romain Rolland may puzzle those unfamiliar with the writer's later career. Rolland, beginning as a pacifist and greatly influenced by Gandhi in the Twenties, became increasingly drawn to Socialism as he got older. As Europe fell into the twin nightmares of war and Fascism, Rolland must have appealed to Schulhoff as a very timely figure.

Compared to the second, Schulhoff's fifth symphony is written with a much broader and heavier brush. He trades his previous subtle wit for hortatory power. Indeed, if you know only his work from the Twenties and early Thirties, this symphony will surprise you. It's a "war" symphony, and no mistake. Ideas are not only repeated, but hammered. Schulhoff wants you to get the point. The expressive meanings lie right on the surface – indeed, come right up to your face, like the classic Che Guevara (Viva Che) print.

In four movements, the symphony opens with martial, mechanized figures, dominated by brass and drums. You can practically see German tanks rolling across the Sudetenland. There's variation here, but little sense of transformation. Schulhoff sticks with these figures and to mainly one key (not even a key, so much as a pedal or anchor tone) throughout the entire movement – an anti-symphonic symphony in that regard. The second movement – an adagio – more or less surveys the battlefield aftermath. It's a gorgeous piece, avoiding the cliches of mourning music, filled with powerful feeling that never steps over to the mawkish. The scherzo (my favorite movement), curiously enough, blends the one in Beethoven's Ninth, especially in the timpani figures, and Vaughan Williams' Sixth. Demons fly and howl through the air, getting more and more distant as we reach the center. They then wheel about and drive back up to the movement's end. The final measures will raise your hair (assuming you have any). The finale, the longest movement in the work by far, gives us heroic struggle against the dark forces and, of course – Socialist Realist dictates being what they were – ultimate triumph. There are hints of what sounds to me like Russian folksong, but only here and there. For me, the movement goes on for far too long. It could have lost five minutes with little problem. Despite some wonderful passages, in general it comes over as too simplistic and too disjointed. So a flawed symphony, but a powerful one.

Against the odds, I have several different performances of the Second Symphony and the Suite. Conlon beats them all. It's easily the first recommendation. The others are good enough, but Conlon seems to bring something more urgent and more individual to the table. The orchestra sounds like it's doing more than a very professional read-through. Conlon also does what he can to bring momentum and shape to the finale of the Fifth. It ain't easy. The sound is good, though not spectacular.

Copyright © 2008, Steve Schwartz