The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Weill Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

Kurt Weill

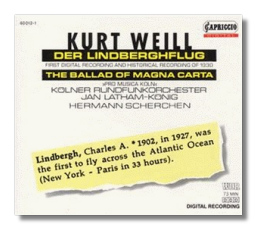

The Lindbergh Flight

- Der Lindberghflug

- The Ballad of Magna Carta

- Weill & Hindemith: Der Lindberghflug (first version; excerpts)

Soloists, Cologne Radio Choir, Cologne Radio Orchestra/Jan Latham-König

Soloists, Pro Musica Köln/Jan Latham-König

Soloists, Berlin Radio Choir and Orchestra/Hermann Scherchen (1930 recording)

Capriccio 60012-1

- Der Lindberghflug

- The Ballad of Magna Carta

- Weill & Hindemith: Der Lindberghflug (first version; excerpts)

Soloists, Pro Musica Köln/Jan Latham-König

Soloists, Berlin Radio Choir and Orchestra/Hermann Scherchen (1930 recording)

Capriccio 60012-1

Summary for the Busy Executive: It was the best of times; it was the worst of times.

In 1940, before the première of his Ballad of Magna Carta, Kurt Weill said to a reporter for the New York Sun, "As for myself, I write for today. I don't give a damn about posterity." In 1929, the buzz over Charles Lindbergh's 1927 solo flight over the Atlantic hadn't even begun to die down, and Weill and Bertolt Brecht conceived of music for the radio celebrating heroism, with Lindbergh as the exemplar. Weill had worked in radio since at least 1925 and written several previous scores (at least one of which has been lost), his greatest in this genre probably the Berliner Requiem. The radio fascinated several major composers of this century and seemed to hold out the promise of a new kind of art, as well as a new kind of audience, outside the traditional concert venue. The "new art" never really panned out. Just about every work written expressly for radio (with the exception of John Cage's Music for 13 Radios and 26 Players) owes its life to live performances. Radio operas like The Old Maid and the Thief keep their hold in the repertory not on radio, but with stage performances and CD recordings. Weill's own Down in the Valley, conceived originally for the radio, has been performed as a stage opera mainly by amateur and student groups and with Weill's help. He converted it and doubled its length. The new radio audience, as we know, turned out to be interested in other kinds of music.

The work was also scheduled for the Baden-Baden music festival run by Paul Hindemith, and the festival theme that year was "collaborative works." Since the festival had commissioned Weill and Brecht's Happy End, the two invited Hindemith to compose some of the numbers. This version premièred in a broadcast by the Southwest German Radio Orchestra under the direction of Hermann Scherchen. Weill, however, did not want the joint score considered definitive and supplied new music to the Hindemith sections fairly quickly. This new version also premièred in 1929, this time at the Kroll Opera. Weill and Brecht sent a presentation copy of the score to Lindbergh "with great admiration."

The relationship between Weill and Brecht - like many great collaborations - heaved and ho'd and finally broke down. Brecht, in my opinion, behaved badly - he put his genius before anybody else's. His business dealings with publishers in at least one case cut Weill out altogether from any royalties, and consequently many of Weill and Brecht's works are mired in a swamp of contracts, counter-contracts, and litigation. Brecht habitually acted unilaterally for both of them. He tried several times to get Weill to work for free, treating the composer as less than an employee, while he himself worked for fee and anything else he could get. For a Communist, Brecht pursued money rather avidly. "Geld macht sinnlich" indeed. In 1950, during the last weeks of Weill's life, in fact, Brecht decided to revise Der Lindberghflug, typically without telling the composer. He removed all reference to Lindbergh by name and inserted a section explaining why he did so. I don't fault him for the revision. Brecht became angry over Lindbergh's isolationist stance in the 1930s and over the flier's advocacy of civilian and city bombing. Weill would likely have agreed. As A. Scott Berg's recent biography makes clear, Lindbergh changed in the popular imagination from young god to tragic hero to demon within the space of about fifteen years. Obviously, Der Lindberghflug has a complicated history. Latham-König performs the all-Kurt-Weill score with the Brecht textual revisions. The CD also includes a performance by Scherchen of parts of the first version - the Weill-Hindemith score.

Aesthetically, the historical difficulties behind the work don't matter a jot. This is a major piece, in a vein similar to Weill and Brecht's Jasager school opera. I've written before that Weill found his artistic voice at a very young age. Most of the music on which his present reputation rests appeared before he was thirty, and he died in 1950, at fifty years old. Because Schoenberg, Adorno, and Webern had written Weill out of serious consideration of modern music and because Weill made money in Germany with Threepenny Opera and in the United States composing for Broadway, some may find it hard to appreciate Weill's genius for innovation, particularly in the theater and the relation of music to dramatic text, and the extent of his achievement. Many major works remain unrecorded. Some of his catalogue has even disappeared. It's ironic that Schoenberg found himself at odds with Weill, because musically the two shared a lot - notably, a musical inheritance from Mahler. I would say that Weill absorbed more Mahler than Schoenberg did, particularly in his musical imagery and his juxtaposition of "high" and "vulgar," but the two do share even more direct links, especially in their harmonic language. Weill once stated that no one could really understand his violin concerto who didn't know something of Schoenberg, and his serious criticism always gave the older man pride of place in modern music, despite his disagreements over whether art music should appeal to a broad audience. Furthermore, in 1928, Schoenberg himself nominated Weill for membership in the Prussian Academy of Arts. For details, see Alan Chapman's "Crossing the Cusp: The Schoenberg Connection" (A New Orpheus: Essays on Kurt Weill. Kim Kowalke, ed. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. 1986. ISBN 0-300-04616-2).

Weill of course differs from Schoenberg in his use of popular dances and musical idioms, adherence to extended classical forms as opposed to Wagnerian "organic" ones, and a kind of Stravinskian irony as opposed to expressionist psychology, in his stage works. The neoclassicism, however, is Weill's and not Stravinsky's. Although "jazz" or cabaret music found itself in the works of many composers from the 1920s on, Weill invented his own: it sounds nothing like Stravinsky, Milhaud, Copland, or Gershwin, to take four very different composers. Creating an idiom or a unique voice may not count for everything, but you don't sneeze at it, either. At a point when many composers were trying to put a new spin on Wagnerian extensions, Weill turned the Singspiel and the operetta to more serious aims, while retaining a "popular touch." To some extent, Brecht's notions of epic theater pushed him in this direction. Often a character in a Weill theater piece sings music at expressive odds with the text. In Dreigroschenoper, for example, Polly Peachum sings a romantic aria - almost a lullaby - after Macheath has cynically left his young new wife for good. Because the music comments not on a character's emotions but on a situation and from a distance, we get something more complex, for the irony has to play off the character's (unexpressed) psychology as well. In this regard, several scholars have argued the influence of Weill on Berg's Lulu (Berg never publicly denounced Weill and even owned some scores of Weill's music), particularly in light of the music of Act III. Der Lindberghflug's text deals in heroic archetypes - again, from a distance. It doesn't depend, except for initial stimulus, on the true character of Charles Augustus Lindbergh himself.

Brecht's text bristles with "double-takes" for the listener, while retaining intelligibility for a radio audience - lots of repetitions of short phrases, for example, so that if you missed something the first time, you'd get it the second or third. Fortunately, this technique suits down to the ground a composer, who relies on repetitions to build musical structures. One section transfigures the traditional "arming of the hero" into a chorus of praise to the airplane. For me, the most interesting part of the libretto shows a typical Brechtian paradox. It turns out that the greatest danger to the pilot comes not from fog, ice, and ocean, but from sleep - seductive and sentimental - just as resisting force of arms is easier than resisting ease and comfort.

Hindemith's sections are wonderful music, even though he probably wrote them between breakfast and lunch, but it's precisely the Brechtian duality and topsy-turvydom that they miss. Hindemith's music in general doesn't express irony very well. It's straightforward in its affect, though not necessarily simple. Weill had solid reasons, other than ego and money, to replace Hindemith's music with his own. Irony flourishes in Weill's music. The flier's account of his plane, a kind of dance-band march, conveys seriousness of purpose, a kind of jauntiness, and a sense of unease all at once. One can contrast the two composers most profitably in the section, "Sleep." For Hindemith, sleep is a pure danger, to which the flier responds as he has to everything else, heroically. For Weill, Sleep sings a sensuous lullaby (if you can imagine it), in a duet between Sleep and the flier. Sleep offers sweet dreams, to which the flier replies, "I'm not tired," in a very weary musical line - moving by semitones, it travels no farther than a whole step – which takes on some of the shape of Sleep's music as well. By these simple devices, Weill shows the power of sleep on the flier. In all, Der Lindberghflug comes across as a complex meditation on heroism, at a time when most of the world wanted heroism pure and simple. The work, like Lindbergh himself, contained depths.

The Ballad of Magna Carta by no means rises to this level. Indeed, it could serve as ammunition for those who see in Weill's American career a sad spectacle of unrelieved decline. The difference, I'm convinced, stems from the relative weakness of artists vis-a-vis producers in the American theater. In Europe, it still is not uncommon to find an artist in the role of producer. On the other hand, our theater was not filled with the likes of Hemingway, Stein, Stevens, Cummings, Fitzgerald, and Faulkner - the hard-core, Modernist, "difficult" artists. Continental theater had Cocteau, Anouilh, Brecht, Kaiser, Chekhov, Strindberg, and so on. Excepting O'Neill, Wilder, and Williams, our theater life has been dominated by competent, even brilliant entertainers like Simon, Kaufman, Hart, and Barry. American radio was even more commercial. What passed for Art in movies, theater, and radio was a sappy apostrophe to the Eternal Verities, with an over-reliance on the Cosmic Fantasy genre. Most of this stuff has been blessedly forgotten, and, please, don't anyone try to revive it. It's doing quite well on its own as The Preacher's Wife, Meet Joe Black, and the latest Robin Williams weepie. In Thirties and Forties radio, its foremost practitioners were Norman Corwin and Earl Robinson, who used a particularly annoying fake-folk rhetoric which nevertheless proved enormously popular at the time. The sentiments are blameless, but the expression of it has become laughable. No sentiment is really earned. It takes a great performer - like Paul Robeson in Robinson's Ballad for Americans - to bring junk like this off. In the Forties, it was turned to explain to the radio audience "Why We Fight." Weill and Anderson's Ballad of Magna Carta is no worse than any of the rest, but it's not good enough to transcend its original propaganda function. If it comes over as smug and patronizing, well… that was the style, as quaint as an ormolu ostrich with a clock in its tummy. Apparently, Weill and Anderson planned this as the first of a series. Thank God they never got around to successors. The performances here are good enough to tell us how enormously bad the piece is. Trust me, Weill wrote better than this while he lived in the United States.

I find the entire Weill-Brecht collaboration an especially fruitful one which, moreover, helped create the modern theater. Scherchen's account of the original Lindberghflug is terrific, despite the static-full 1930s broadcast quality. Furthermore, the announcement of the various sections in German, French, and English interests me in that it shows how small a place Europe is and how varied the audience for essentially a local broadcast. Latham-König comes up with a crisp reading of the revision in decent, though not state-of-the-art, stereo sound. A fabulous work, decently played.

Copyright © 1999, Steve Schwartz