The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- J.S. Bach Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

Johann Sebastian Bach

Harpsichord Works

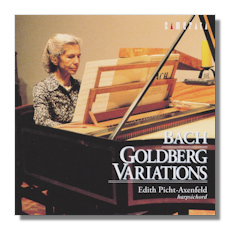

- Goldberg Variations, BWV 988

- Italian Concerto in F Major, BWV 971

- Chromatic Fantasia & Fugue in D minor, BWV 903

Edith Picht-Axenfeld, harpsichord

Camerata CMCD15122~3 2CDs

Harpsichordist and pianist Edith Axenfeld was born in 1914 in Freiburg, Germany. Among her teachers were Rudolf Serkin, Wolfgang Auler and Albert Schweitzer. Her long and successful career began in the 1930s, but was interrupted by the Second World War. It effectively resumed after she married the director of the Birklehof Boarding School in Hinterzarten (Schwarzwald) and took his name, becoming known as Edith Picht-Axenfeld. Although she became most famous for her performances of Bach and Beethoven, her repertoire was much wider – extending even to Ligeti and Nono taking in Chopin and the 19th century Romantics. She was also successful – in an unusually long career – as a teacher and chamber music performer. She died as recently as 2001.

There are barely a dozen and a half CDs in the current catalog featuring Picht-Axenfeld's work. But within the last six months, the Tokyo-based label, Camerata, has released obviously much earlier recordings of her Bach recitals and performances. In addition to the Goldberg Variations, which take up the whole of the first disk here and ten tracks of the second, this excellent release also includes sparkling accounts of Bach's Italian Concerto in F Major, BWV971 and Chromatic Fantasia and Fugue in D minor BWV903. Playing a harpsichord by the American pioneer of the historical instrument movement, William Dowd, Picht-Axenfeld's interpretations are down-to-earth, upright, transparent and clean. There is no room for romantic lingering, the infusion of personal tinges or wistfulness. At the same time, Picht-Axenfeld's are not over-muscular readings, nor cold, nor too steely.

One senses that Picht-Axenfeld was aiming to offer us a Goldberg Variations somewhat in the spirit of the exemplary keyboard exercise that Bach intended; not a highly personal account in the style of Glenn Gould or Rosalyn Tureck, of whose interpretations there are no fewer than half a dozen CDs currently available. The danger with this approach is that each variation devolves into merely something to be played, dispensed with and moved on from. They line up, are played and disappear sequentially with little or no acknowledgement of the Goldberg Variations' structural cohesion or of the ways in which the variations interrelate and progress from one to the next. It takes nerve and technique both to present each variation as something different; yet to do so from the standpoint that each remains not only a variation of the original ground bass, but that each is characterized by significant… variety.

Picht-Axenfeld achieves this balance laudably. In part her success derives from a tension between her playing as emblematic of self-control, of centered, non-nonsense exposition on the one hand; and an expressive, at time almost wry sense that the music is waiting to burst out of any notional constraints with everything from humor to anger, cosseting to love. There is nothing wayward about her playing; nothing eccentric or unduly personal. At the same time, it's neither intimate nor clinical. Picht-Axenfeld has her stamp on what is nevertheless "personal" music, "confidential" even, by playing on and implicitly (though never heavy-handedly) exposing and commenting on the tension between what for most listeners will be very familiar music and its immense stature and depth. She always has much in reserve, much energy, much latitude of expression, and a quiver of potentially quite contrasting colors, angles, and even tempi. In other words, this music is totally her own. The same goes for the two substantial fillers: they're played with grace, style and efficiency. As with the Goldbergs, the expression is never quite released at full force. But they are compelling accounts.

Given their age (these performances were recorded in Japan in September 1983), the acoustic is remarkably good. There are half a dozen moments when a slight metallic modulation in, presumably, the taping can be detected. But such imperfections very much take second place to the warm and nicely responsive acoustic of the House of St. Gregorius, Higashi-Kurume, in Tokyo. The short booklet contains a brief introductory essay by Christoph Wolff setting the Goldbergs in the context of Bach's Clavierübung and the former's numerical underpinnings.

This Goldbergs is unlikely to be your first choice, or one to live with indefinitely forsaking all others. But it's a good, serviceable and technically unobtrusively brilliant recording which (to quote Goethe) neither rushes nor rests.

Copyright © 2012, Mark Sealey.