The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

-

Pettersson Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

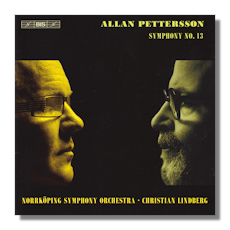

Allan Pettersson

Symphony #13

Norrköping Symphony Orchestra/Christian Lindberg

BIS SACD-2190 Hybrid Multichannel 66:46

Allan Pettersson (1911-1980) was a Swedish composer whose music is taut, exciting, imaginative and sufficiently original that it deserves to be better known. Pettersson was the youngest of four children whose father was a violent, alcoholic blacksmith. Pettersson's life was marred by persistent ill-health and at times adverse composing conditions. An individualist who composed mostly large-scale symphonies (although his First Symphony from 1951 remained unfinished), he has slowly gathered a following only at and after the end of his career.

The ever-enterprising Swedish label, BIS, has played no small part in legitimizing and promoting Pettersson's symphonies in a series now nearing completion from the Norrköping Symphony Orchestra, with both Leif Segerstam and – as here – Christian Lindberg. This recording of the work, which is in one long movement of varying tempi lasts over an hour; the 12 continuous tracks on the SACD mark various points denoted as so many bars after Figures in the score.

It's a performance that exudes confidence. Not bravado nor undue muscularity. But openness and expansiveness of phrasing – in the way that the best accounts of Sibelius' symphonic writing do. Pettersson's music is not, though, swamped by swirling strings with mere undertones of cliché-hampered Nordic emptiness. The composer was intelligently influenced by his studies with Bartók, Hindemith, Maurice Vieux, Karl-Birger Blomdahl, Tor Mann, and Otto Olsson. Pettersson writes very much in his own voice; and that personality has, perhaps, the masculinity and assurance of many Scandinavian composers.

But this sure-footedness is never to the detriment of subtlety, variety or emotional richness. Significantly, one of the achievements of the BIS cycle has been to promote this distinct musical style. The music is presented for what it is. It's not smuggled away in an attempt to make the music sound more "universally" appealing. At the same time Pettersson's distinct way of writing is respected; it's treated so as to make it accessible. The criticism could be leveled at these symphonies of a certain "sameness". So the surprisingly accomplished Norrköping Symphony Orchestra has been at pains to emphasize the music's exact nature, and not an impression thereof.

An accomplished violist (until ever more debilitating rheumatoid arthritis made playing impossible), Pettersson's use of instrumental color in support of thrusting melodies and large scale thematic development in the style of Mahler as much as any of his contemporaries makes his music stand out. Experiments with formal counterpoint as well as atonality clearly equipped him to become as accomplished as he did in deconstructing the symphonic form to produce music that reaches in and grabs the listener. He said of his music from the 1950s, for instance, "…I am always breaking up the structures… [and] … creating a whole new symphonic form".

All these characteristics are evident in this splendid performance of the Thirteenth. Little runs on the deeper brass set against wisps of tutti strings as if they introduced them. "Interventions" by the percussion which imply fixity and omnipresence, a little like the way Carl Nielsen used that orchestral family. Large, strident open intervals in the upper brass and woodwind with strings up and down the scales. Strong, but not overtly "daring" contrasts in dynamic which seem to have little to do with the innate characteristics of the instruments; but in fact move – almost push – the thematic structures of the music inexorably forward. Unapologetic piling of unrelieved tension of key as if to emulate the pedesis of a storm, though where rain and color, volume and vector of the clouds impinge on our understanding of what surrounds us as much as does the apparent uncontrollability of wind… the passage from Figure 70 [tr.4] is typical.

Oddly, analogous use of melody, texture and uncompromising sense of direction can be found in the larger-scale compositions of Pettersson's contemporary, Benjamin Britten. In each case, the impact is never one of unbridled dynamism for its own sake, or for mere effect. And concomitant (self-)control marks this interpretation of Lindberg and the Norrköping Symphony Orchestra. The result is elegance and the delicacy of a tree – but a cedar in color, not a willow in silhouette.

The Symphonies' conception never strains, nor suggests strain. Yet the music is strenuous, tight, potentially unhappy. It affects us in the way that an unhappy person (for so must Pettersson have been) is able to imply happiness from their own oppression without being cheery. And without surface joy. Neither is it easy to sustain a work as long and insistent as this Thirteenth Symphony without resorting to the boisterous or the pointlessly unrelenting. These players have the finesse and depth of understanding of Pettersson's world to avoid both. They make every bar and nuance interesting despite – one thinks of the unrelenting first movement of William Walton's First Symphony – an awareness that they may all be leading to the same place. Havergal Brian's gigantic symphonic thinking also comes to mind.

They do this by neither continually withdrawing such a goal or endpoint as fast as the listener begins to expect it; nor by deliberately meandering, serendipitously riding on a horse of many colors in an equally dappled landscape devoid of any safe haven. For, unlike Walton or such extended movements as the last of Mahler's Third, Pettersson is constantly striving and opening new doors.

These players are utterly comfortable with such an idiom without at the same time conferring spurious novelty value on it. It's true that we rarely know – on first and even subsequent hearings – where the music of this consummate symphonist is "leading". But that's not the point. The fact that their technical tidiness, attack and judicious use of dynamics here are as sharp as they are also aids: the music is rarely as subdued or blustery, because neither makes an impact in Pettersson's musical world.

The acoustic of this recording is everything one would expect from BIS, the Louis de Geer concert hall in Norrköping, which is in the province of Östergötland in eastern Sweden. It's not so spacious as to add its own voice to the recording. But it allows the music to breathe both as a whole and as individual instruments and groups make their contributions. The booklet sets the scene for the Thirteenth; then outlines some of the challenges for players as well as listeners. This recording, with the same players of the 85-strong orchestra who saw its first Swedish concert performance, in 2014, nearly 40 years after its completion can be warmly recommended. For those collecting the set from BIS, this CD will be bought without hesitation in preference to the only other recordings, by the BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra under Alun Francis, on CPO (the complete set 777247-2 and the Thirteenth singly 999224-2). For anyone new to Pettersson's distinct symphonic world – despite suggestions that, as hinted, the listener can find it hard to orientate themself – it's a good place to start.

Copyright © 2016, Mark Sealey