The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

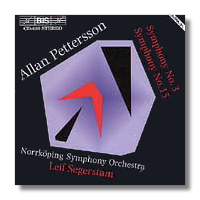

Allan Pettersson

- Symphony #3 (1954-55)

- Symphony #15 (1978)

Norrköping Symphony Orchestra/Leif Segerstam

BIS CD-680 70:52

Summary for the Busy Executive: Ladies and gentlemen, hold on to your hats. We are taking a ride through hell.

Of all Scandinavian composers excepting Nielsen and Sibelius, Pettersson has the most to say to me. He conforms to no Northern stereotype. Joy in nature, for example - so prominent in writers like Grieg, Tveitt, and Nielsen - finds no place in his work. Indeed, one meets with joy only rarely, if at all, in Pettersson's output. Pettersson's music grits its teeth against pain and demons, and he suffered from quite a bit of both, from a childhood that would have made Little Nell's seem rosy up through an agony-filled arthritic adulthood that kept him confined almost to one room. Transcendence, if it comes (and there's no guarantee), is hard-won and highly provisional.

Although he wrote well in a few other genres, the center of Pettersson's achievement lies, for me, in his cycle of fifteen symphonies (numbered 2 through 16; the first symphony is at this moment lost). The works in Pettersson's catalogue, with few exceptions, always strike me as marathon runs - not that they're necessarily long, but they do take mental stamina. It's not the tired question of tonal vs. Atonal, either, that makes them so. The symphonies are firmly tonal. However, they are also packed with ideas, all of which the composer continuously varies.

The Third typifies Petterson's method. For many years, he considered it his best symphony, and one can see why. The argument and its presentation are relatively clear. The orchestration is - compared to something like the second violin concerto - lean and mean. The work falls into four movements - moderato, slow, scherzo, and allegro finale - the last three played without a break. But that's about where its relation to the traditional symphony stops. As far as I can tell without a score, all the thematic material derives from a single opening idea, again continuously varied. Pettersson plays with a shape as much as with actual notes - turning it upside-down, flipping it backwards, changing an interval here and there to tremendous effect, altering its rhythms and tempi. The symphony begins with an introduction where ideas jostle against and interrupt one another. You begin to wonder how you will keep all this stuff in your head. Then you realize that it's the same essential idea in different guises. The main rhetorical gambit is the violent interruption, as the texture and character of the music changes, and this sets up a tension with the thematic unity of the work. Pettersson keeps threatening to rip everything apart texturally even as he stitches it all together thematically. In the last three movements, the end of one movement foreshadows the beginning of the next - an update of Beethoven's famous transition from the scherzo to the finale of his Fifth. However, this is most obviously true between the first and second movements, even though the composer specifies a normal interstitial pause. The last two notes of the first movement become the first two notes of the second. Still, this is not the usual symphonic building of a seamless argument that gets you from here to there. Pettersson employs the musical equivalent of movie jump cuts. There are more violent gashes in this work than in the face of Karloff's Frankenstein.

The second movement flows the smoothest, with nevertheless the occasional head-snapping shift, but the layout of the argument occurs over a very long span. This movement also contains some of the few moments of Petterssonian tenderness, but melancholy never stays away too long. Sharp dissonances gradually intrude, only to subside, like waves of pain. I experience the movement overall as resignation.

The third movement begins with the worrying of tiny ideas, like someone feeling out his toothache with his tongue. It finally explodes into the finale. Again, one feels the disjointedness of the movement, as if it can't decide whether it's a Mahlerian Ländler, waltz, or march. Ideas - or rather gestures, since all ideas in this symphony are siblings - from earlier movements are recalled. Pettersson builds up a terrific head of steam nevertheless, and the power of it all carries you over the jumps and twists. It's a nightmare landscape - ghosts and demons soaring and screaming across desolation. This is the real soundtrack of Mordor. Toward the end, we hear a deeply-felt lament - almost chorale-like - but it doesn't lead to glimpses of heaven. It tries to settle for a way to end. The music burbles with a questioning figure, tries for a burst of anger, which fizzles almost immediately, and ends on the abrupt question. In feeling, it reminds me of the epilogue to the Vaughan Williams sixth, except that Pettersson doesn't indulge himself with the luxury of space. He presents his enigma more directly than Vaughan Williams does his, and seems to point to something bleaker as well.

Swedish television commissioned Pettersson's Fifteenth, but as the liner notes point out, Pettersson usually filled such obligations with works he was writing anyway. The economy of idea which we encounter in the Third has become even more stringent. In fact, one doesn't meet themes as much as gestures: richly-scored chords in isolation, scurrying strings, drum rolls. The symphony plays out in one movement, with major subdivisions: a battleground of an allegro, a slow lament, in which the opening material reappears in longer note values and less aggressively, a conflict between the battle and the lament with some question as to which will win out.

As I say, the first movement rolls across like a war. It builds to a terrific climax and breaks into a troubled lament, like the drizzle that hangs on after a huge thunderstorm. Gradually, another front moves in, and we get to a rhetorical conflict between the music in long notes and the music in short ones. Toward the end, the music seems to settle into a chorale-dirge, but even here the martial elements intrude and threaten to overwhelm. For Pettersson, symphonic growth comes through conflict, and the resolution is in doubt to the end. "Resolution" is probably the wrong word. Nothing is psychically resolved. The slow music wins out but by taking on the aggression of the fast, and this symphony also ends without settling anything.

Segerstam and his orchestra take up these works like heroes. Not many people program Pettersson in the first place, because it takes a commitment to hard work - mental, as well as musical - without any guarantee of reward, even the reward of praise. While I can imagine both symphonies better played, these performances burn with dedication to Pettersson's austere world, and kudos to Bis for making these things available. Pettersson I doubt will ever become a popular taste, but his adherents are a fierce bunch, hungry for more.

Copyright © 2003, Steve Schwartz