The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Prokofieff Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

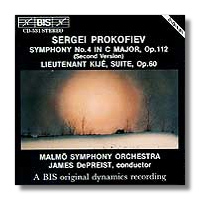

Serge Prokofieff

Symphony #4, Revised

- Symphony #4 in C Major (second version)

- Lt. Kijé Suite

Malmö Symphony Orchestra/James DePreist

BIS 531 - 63min

The 50th anniversary season of the Boston Symphony was unlike any similar celebration before or since. The orchestra's first music director (George Henschel, then 80 years old) returned to recreate his initial concert. Henschel's successor, Serge Koussevitzky, arranged a spectacular series of commissions from the leading composers of the day. Several enduring masterpieces resulted, including Stravinsky's Symphony of Psalms, Albert Roussel's neo-classical Symphony 3, and Howard Hanson's Romantic Symphony. A host of lesser works were also launched during that memorable season, such as Hindemith's Concert Music for Strings and Brass, Copland's Symphonic Ode, and Prokofieff's Symphony 4.

As with the Symphony 3, based on themes from his unperformed opera The Flaming Angel, Prokofieff's new score borrowed material from an earlier stage work. In this case, the composer selected themes from The Prodigal Son ballet, which he felt would benefit from symphonic treatment. In Prokofieff's own words, the première "was not a success" and subsequent performances were few and far between. For reasons that remain unclear, Prokofieff subjected the score to a major revision in 1947. Perhaps influenced by the success of his heroic Fifth, the composer transformed a witty, neo-classical, and mildly dissonant essay into a bloated, bombastic, thickly-scored, and crass symphony in the Soviet Socialist-Realist tradition.

A few adventurous conductors such as Martinon, Rostropovich, and Järvi have recorded the Fourth Symphony's first version. While not representative of Prokofieff at his best (the thematic material is generally weak and undistinguished), the original Fourth does have its charms. The development section of I, completely replaced in 1947, is especially noteworthy for its spiky dissonances and abrupt shifts of mood and texture. The revision preserves the lackluster themes of the original, but purges the score of virtually all traces of its unique blend of sarcasm and bite. The alterations range from unnecessary (the addition of a slow introduction to I) to downright embarrassing (the piano syncopations of the main theme in II).

Like Eugene Ormandy, whose excellent CBS recording has yet to appear on silver disc, James DePreist minimizes the revised score's bombast and very nearly succeeds in bringing this monster to life. While the Malmö Symphony is no match for Ormandy's Philadelphia Orchestra, the ensemble does play exceptionally well. The strings have a rich and lovely tone that would have made Ormandy proud, and the soloists (especially the flute and piano) are outstanding. Bis's engineers contribute a warm, reverberant, yet finely detailed sound. For his part, DePreist's conducting is fiery and spirited. He makes the most of the sharp contrasts between the slow, lyrical sections and the faster, dramatic moments in I. The conductor also has a superb sense of balance, and he uses the percussion to maximum effect. In III, De Preist's touch is light and delicate, and in his capable hands this movement sounds for all the world like a rediscovered number from Prokofieff's masterpiece, Roméo and Juliet.

Unfortunately, DePreist's Kijé is routine and uninspired. The solos (with the exception of a marvelously expressive double bass in II) are utterly lacking in character, warmth, or power. Here the BIS's engineers also fail, giving us a distant, unfocussed sound.

In short, if it's Kijé you want, enjoy Fritz Reiner while you look for a used copy of Erich Leinsdorf's Boston Symphony LP from RCA (with baritone David Clatworthy in II & IV and a knock-out version of the "iron and steel" Symphony 2). But, should you wish to make the acquaintance of Prokofieff's least-known symphony in its final form, this disc is an excellent investment.

Copyright © 1995, Tom Godell, All Rights Reserved.

This review originally appeared in the American Record Guide