The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Theodorakis Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

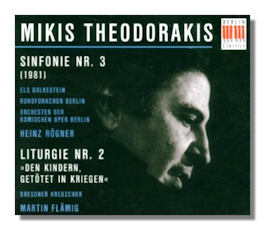

Mikis Theodorakis

Works for Orchestra & Chorus

- Symphony #3

- Liturgy #2 "Children Killed in War"

Els Bolkestein, soprano

Komische Oper/Heinz Rögner

Dresdner Kreuzchor/Martin Flämig

Berlin Classics 0011282BC 2CDs

Symphony #3 only reissued on Berlin Classics 0032412BC:

Amazon

- UK

- Germany

- Canada

- France

- Japan

- ArkivMusic

Or as above with Axion esti, Canto General & Passion of Sadducees reissued on Berlin Classics 0002802CCC:

Amazon

- UK

- Germany

- Canada

- France

- Japan

- JPC

Mikis Theodorakis' choral Symphony #3 is a sad, thrilling, sprawling, sporadically exultant work. Throughout its 70 minutes, it is muscular and flabby, sentimental and harsh, modernist and romantic, lucid and puzzling. Based mostly on the nineteenth century poems of an obscure Greek poet, Dionysios Solomos, the symphony relates a mother's grief over her two sons' deaths. Can any lines be more gloomy than these? "Two poor brothers sleep beneath them/the irreversible sleep of death/and their mother lost her mind." Through such poetry, Theodorakis constructs an eerie, sometimes incoherent elegy about loss.

Its first movement establishes a melancholic mood, reminiscent of Górecki's Symphony of Sorrowful Songs and Dmitri Shostakovich's Symphony #14. With eloquent timing and restraint, the chorus mourns the loss. When the mood becomes too despondent, Theodorakis throws in an agitated presto, like an urgent swig of Ouzo. Before long, he plunges again into the pit of grief. Dissonant voices shatter the second movement's repetitive themes, perhaps designed to convey the tormented mind of the mother. In this busy movement Theodorakis alternately breaks down and reconstructs his tonality, but why? To contrast lucidity with confusion? Excerpted from Theodorakis' Good Friday liturgy, III is a bland religious poem about graveyards. The music, while not bland, veers into the melodramatic, like a B-movie score. Soprano Els Bolkestein injects some passion between the clanging bells and thick orchestration, but really rages amid the clash and clang of IV. Ultimately the piece works, both as a meditation on and a defiance against grief. But like most Woody Allen films, it cries out for the red pen.

While it uses Tasos Livadhitis' secular poetry about children killed in recent wars, Theodorakis' Liturgy #2 is composed in "the olden style," much like Prokofieff's Symphony #1 ("Classical") or concerti grossi by Alfred Schnittke and Ellen Taafe Zwilich. Composed for chorus only, this piece respects the medieval liturgy format with its charming melismas and intricate polyphony. It even sounds religious, and perhaps is "spiritual" in the pop-culture sense. Most of Livadhitis' lines lack bite and seem archaic, declaiming that death is a "teller of black secrets," and that his generation, a lost generation, is "all tears and grief." However, real poetry sometimes breaks through, such as "holy is liberty/and the world's grief is a broad banner/that greets Che Guevara's shadow."

I don't quite know what to make of this work. Undeniably, the counterpoint is skillfully constructed and there is enough variation and melodic invention to keep it unfolding from poem to poem. But has Theodorakis produced a successful exercise rather than a daring work, like his Canto General a decade earlier? The Dresdner Kreuzchor, conducted by Martin Flämig, performs admirably, even memorably. Someday I would like to see it performed. Once. Yet Liturgy #2 does not instill in me a desire to hear it again, nor does it spur me to hear Liturgy #1. It lacks drama, irony, and commitment, traits we have come to expect from Greece's greatest living composer.

Copyright © 1998, Peter Bates