The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

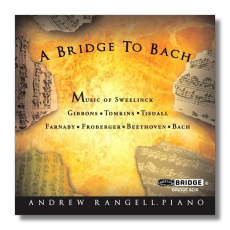

A Bridge To Bach

- Orlando Gibbons: Lord of Salisbury Pavane and Galliard

- Jan Pieterszoon Sweelinck:

- Mein junges Leben hat ein End

- More Palatino

- Unter die Linden Grüne

- Fantasia (G Dorian)

- William Tisdall: Pavana Chromatica (Mrs. Katherin Tregians Paven)

- Thomas Tompkins:

- A Sad Pavane for These Distracted Times

- Pavane

- Voluntary

- Johann Froberger:

- Ricercare VI in C Sharp Major

- Ricercare XIII in C Major

- Ludwig van Beethoven: Fuga, Op. 131

- Giles Farnaby: Loth to Depart

- Johann Sebastian Bach: Sinfonia in F Major

Andrew Rangell, piano

Bridge BCD9216 DDD 65:23

Andrew Rangell always has something interesting to say. After making a series of provocative recordings, mostly Bach and Beethoven, for the Dorian label (R.I.P.), Rangell was adopted by the good folks at Bridge, where he has continued to make unusual recordings that are both intellectually and emotionally satisfying.

This time around, Rangell has assembled a program of music composed mostly during the first half of the 17th century – several generations before Johann Sebastian Bach was active. In his extended yet very readable booklet note, Rangell explains this disc's overall title. In some of this music, "one can hear fleeting soundprints of Bach," but that is not precisely what Rangell is trying to get at. "The resemblances are noteworthy," he writes, "but the larger point, for me, is that in the area of articulation, contrapuntal balance, imaginative ornamentation, and rhythmic definition, Bach himself has been my most valued tutor in the study and appreciation of his predecessors."

I'm sure that Glenn Gould, one of the past century's most outstanding interpreters of Bach, would have agreed. Among Gould's recordings is a collection of music by William Byrd, Orlando Gibbons, and Jan Pieterszoon Sweelinck (Sony SMK 52589). At one point, Gould claimed that Gibbons was his favorite composer, and that composer's Lord of Salisbury Pavane and Galliard is common to both the Gould disc just referenced and the Rangell disc here reviewed.

For Gould, Gibbons also must have been a "bridge to Bach." There's no mistaking Gould for Rangell, or vice versa, but both pianists clearly adore this music. Both performances are quietly contemplative, and with their perfect proportions and clarity, they make listeners feel that all is right with the world. The same can be said for everything on A Bridge to Bach. The dexterous Rangell uncovers the beauty in all that he touches. He is like one of those professors in college who makes biology or physics not just understandable, but miraculous – even to English majors!

Like Gould, Rangell plays this music not on the keyboard instruments of the early to mid 1600s, but on a modern piano. (In Rangell's case, this is a Hamburg Steinway D.) These recordings, then, will be of little use for authenticists – forgive the neologism, but it seems appropriate – but will deeply satisfy those who believe that the message is more important the medium. Even more than Gould, Rangell uses the piano's full resources to play this music, and this gives his performances colors, excitement, and relevance of their own. Rangell also has a clear advantage in terms of engineering. Bridge's sound is far superior to what Columbia was giving Gould in the 1960s.

Copyright © 2007, Raymond Tuttle