The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

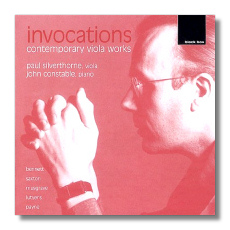

Invocations

Contemporary Viola Works

- Richard Rodney Bennett: After Ariadne

- Thea Musgrave: In the Still of the Night

- Elisabeth Lutyens: Echo of the Wind

- Robert Saxton: Invocation Dance & Meditation

- John Hawkins: Urizen

- Anthony Payne: Amid the Winds of Evening

- Colin Matthews: Oscuro

- John Woolrich: 3 Pieces for Viola

- Stuart MacRae: The City Inside

- Arthur Kampela: Bridges

- Jukka Tiensuu: Oddjob

Paul Silverthorne, viola

John Constable, piano

Black Box BBM1058 75:28

Summary for the Busy Executive: One of the year's best.

Compared to their violin-playing colleagues, violists have to work to find repertoire. Where a Perlman has his pick of music from baroque to the latest up-to-date, and from just about every major composer along the way, the violist generally makes do either with arrangements or with music beginning at the twentieth century. Off the top of my head, I can name only five repertory works that have some cachet with the general public: Berlioz's Harold en Italie, Mozart's Sinfonia Concertante, Strauss's Don Quixote, the Bartók concerto, and the Shostakovich sonata – hardly enough to build a solo career on. Hindemith wrote a ton for the instrument, which happened to be his own, but Hindemith's music has undergone an eclipse. While there are many other fine pieces for the viola, I doubt most non-violists know them, in the same way that they know (and actively want to hear) the Beethoven violin concerto or "Kreutzer" sonata. Similarly, few violists – that is, players who have come to public notice through the viola – have penetrated public consciousness. One thinks of the great Lionel Tertis, William Primrose, Yuri Bashmet, Kim Kashkashian, Paul Doktor, Daniel Benyamini, and Walter Trampler, although if one looked, one could find other fine musicians like Abraham Skernick, Cecil Aronowitz, Tabea Zimmermann, Dimitri Shebalin, Carlton Cooley, and Joseph di Pasquale. In short, you wind up with as many well-known violists throughout the history of recording as you do of violinists in just about any given year.

I don't know why these conditions prevail, since I greatly prefer the sound of the viola to that of the violin, which to me tends to "squeak." Perhaps the lack of concerto literature, heroic parts, and so on., give rise to instrumentalists at home more as equals in chamber groups than as stars in the spotlight. Paul Silverthorne has in a way run against the grain of the kind of violist you normally hear. He can play subtle, but he can also play with fire and call upon a "star-quality" tone that demands a listener's attention. Nevertheless, he doesn't indulge a "one-size-fits-all" approach. His color and approach change suitable to the music he performs. His Brahms sounds little like his Shostakovich. Furthermore, he has done his bit to increase viola repertoire by commissioning composers. Not only that, but composers apparently enjoy writing for him. Early on, he found himself in Elisabeth Lutyens's orbit. Lutyens, an important British composer whose music so far has remained shadowy outside of Britain, taught some of the best of their generation.

This CD gathers together Lutyens and her circle, as well as others. The music takes a little effort, but it also rewards the effort. You won't find an out-and-out dud in the entire program, and you will encounter at least two stunners. Furthermore, you place yourself in the hands of two master interpreters – Silverthorne and pianist John Constable – who've played together for years.

The program opens with one of its strongest pieces, Richard Rodney Bennett's After Ariadne. Bennett made his first splash in the Fifties, notable both for his jazz-based pieces and for his forays into dodecaphony. He has also enjoyed some success in commercial fields, notably his film music, particularly his much-admired score for Murder on the Orient Express. He has also accepted such assignments as orchestrating Paul McCartney's Standing Stone. One's impressions of a composer obviously arise from the pieces one has heard. The spottier the acquaintance, the less reliable the judgment. I had thought of Bennett as technically brilliant, facile, but ultimately uninvolving. After Ariadne turned me around. This major work, a single movement lasting almost a quarter hour, grows out of its opening notes – pretty much monothematic, in fact. To some extent it's a fantasia, but one with great structural cohesion as well as a solid dramatic plan. Bennett has shaped something original, sui generis, and substantial. It yearns, it sings with great tenderness and a noble, slightly restrained passion. Toward the end, the theme begins to break free of its dissonant setting and resolve into "Lasciate mi morire" (also known as "Lamento d' Arianna") from Monteverdi's sixth book of madrigals, thus illuminating the title. We get a straightforward quote from the madrigal, before the mists rise again and surround the theme.

At this point, the Scottish composer Thea Musgrave has made her reputation on her operas. She may be as familiar in the U.S. As in Britain, probably due to her long residency here. The title In the Still of the Night of course conjures up the Cole Porter song, but Musgrave doesn't have this in mind. Instead, she writes a nocturne for viola alone. The work has a weight all out of proportion to its length. It proceeds with the stateliness of a Bach sarabande.

Elisabeth Lutyens, daughter of the great British architect, has immense importance as both a teacher and as an historical figure in British music. One of the earliest British serialists, her music shows a rare, practically Webernian refinement. Indeed, that may lie at the root of her lack of acceptance even among new-music people. Recordings of her music show up once in a blue moon. I treasured an LP of her "O saisons, o chateaux," bankrolled by the Gulbenkian Foundation. Major scores go unperformed and unrecorded. Echo of the Wind for solo viola is another night piece. It is the devil to play, exploiting rapid passages of high harmonics and changing colors practically with every measure. Note that we don't get the wind itself, but its echo, wisps of wind as it were. It seems written serially (I can't be sure without a score), but that misses the larger rhetorical and architectural point, a three-part structure laid out as a dynamic arch.

Robert Saxton's Invocation, Dance, and Meditation is yet another arch. It begins as a kind of cross between Bloch and Britten (of the Holy Sonnets of John Donne), with a slow, quiet opening. Eventually, both the tempo and dynamic increase, and the rhythms become more agitated until we find ourselves in the middle of a dance. Things then slow down and quiet down to the end. Saxton admits to the inspiration of Hassidic prayer. Of all the works here, it runs to the more conservative side of things, particularly surprising from a student of Lutyens and Berio, but it's still a solid piece.

Currently one of my favorite British composers, John Hawkins, a student of Lutyens and Malcolm Williamson, has built an impressive body of work and a solid reputation among British musicians. Recording companies have yet to discover him, but I believe they will. A roster of distinguished performers champion his work. Again, he comes from the conservative wing. The shade of Hindemith lurks behind Urizen, but that indicates merely a starting point. Hawkins speaks his own poetry. Urizen, of course, is William Blake's demon of eighteenth-century rationality, usually the villain of his longer poems. I confess I don't see much relation between Blake and the music, even when Hawkins goes so far as to quote a passage in his remarks, but fortunately the piece's success doesn't depend on a program. This piece combines structural rigor – two or possibly three ideas constantly put into new relationships with one another – with a darkly dramatic sensibility. Hawkins has also written pieces under the inspiration of the sea, and this piece strikes me as coming from the North Atlantic. It begins with a lengthy intro for solo viola, in which the composer lays out his basic ideas. Most solo-instrument passages bore me to death, but this grabs my attention and shuttles me along. The piano enters, and we get an almost-bluesy passage as the piece works itself into a neurotic, passionate waltz before it dies down toward the end.

Colin Matthews, a student of Nicholas Maw, hung around Britten and Imogen Holst in a kind of apprenticeship. Due to his "completion" of Gustav Holst's Planets with a "Pluto" movement, he's probably the best-known composer on the program. I don't particularly care for his work in general, and Oscuro doesn't prove an exception. It sticks to the viola's middle and lower range and supports it with an even lower piano. It never goes anywhere with any real point. A gray piece stuck in bland.

His brilliant "elaboration" of Elgar's Third Symphony from the composer's scraps and late incidental music showed at the least that Anthony Payne knew his Elgar. It prompted me at the time to seek out Payne's original music. The enterprising British label NMC has recorded a number of his works. Silverthorne may put Among the Winds of Evening so close to the Lutyens. Compared to Echo of the Wind, the Payne, also for solo viola, appears a bit raw. However, it also works more directly on a listener's feelings. It begins in a "painterly" way, depicting not gentle evening breezes, but gusts, and builds to passionate cries.

The wind and sea also inspire John Woolrich's 3 Pieces for Viola. Or, rather, three musical evocations do: "Soave il vento" from Cosí fan tutte, "Torna il tranquillo al mare" from Monteverdi's Il Ritorno d' Ulisse in Patria, and Monteverdi's madrigal "O sia tranquillo il mare" from Book VIII. It pursues the same strategy as Bennett's After Ariadne, but on a much smaller scale – epigrams, rather than meditations.

Saxton's pupil Stuart MacRae wrote his City Inside out of a childhood memory of a thunderstorm at night. Once again, the painterly yields to the dramatic, as the depiction of pelting rain moves into inner storms of Bernsteinian cross-rhythms.

The program winds up with scores by Arthur Kampela, a Brazilian living in New York, and the Finn Jukka Tiensuu. Both composers probably write the most "advanced" music here, and both contribute strikingly similar pieces. Both explore a new kind of polyphony, within the framework of a solo viola, and both try to trick the ear into believing it listens to more than one instrument. Kampela's Bridges does this by distinguishing "tone" and "noise" and by exploiting simultaneously the two extremes of the viola's range. Tiensuu's Oddjob creates the illusion of two instruments through electronic echo and delay as well as by sharp stereo separation. Both pieces are brilliant and bravura fun, in a way similar to Liszt's Hungarian rhapsodies, without partaking of that idiom.

Silverthorne sails through all of this. The virtuoso technique one tends to take for granted. However, his ability to make living music over a gamut of contemporary styles really impresses. He's not just playing notes. He shapes each piece and gives each one a strong forward impulse. It's almost as if he's in each composer's head. And Constable is his equal. Beautifully recorded, besides.

Copyright © 2007, Steve Schwartz