The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

Article

Article

A Latter-Day Ysaÿe

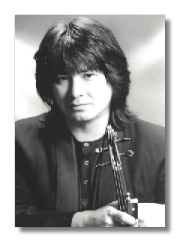

Martin Anderson talks to Marat Bisengaliev

The Kazakh violinist Marat Bisengaliev first came to my attention thanks to his epic performance of the Havergal Brian Violin Concerto on Marco Polo (8.223479, reissued on Naxos 8.557775), a recording that easily made it into my Want List at the end of 1994. That Bisengaliev was prepared to take up this extraordinarily difficult work and memorize it for the recording is an indication both of how good a violinist he is and how light he makes of his own prodigious gifts. Indeed, David Denton, who runs the British branch of Marco Polo and Naxos, told me in a voice which made no attempt to hide considerable admiration: "He's just amazing – the violin part was apparently too difficult to read from, so he simply learnt it!" Simply?

It was through the Brian Violin Concerto that I came to meet Marat Bisengaliev, who was giving the work its first public airing since 1979, when the late Ralph Holmes last played it in London with the Young Musicians Symphony Orchestra under James Blair. Since the two other occasions on which Holmes played it, in 1969 and 1981, were both in the studio, Bisengaliev's performance – in May last year, with James Kelleher and the Millenium Orchestra, an amazingly good scratch band assembled from young London professionals – was only its second outing before an audience. (David Denton points out that the violin part had never been heard in public as the composer intended: Ralph Holmes had rounded out some particularly awkward corners in the interests of playability.) The concert marked the twenty-first birthday of the Havergal Brian Society, one of the most successful of the UK composer societies; incidentally, it also included the first-ever performance of a suite arranged by Malcolm MacDonald from Brian's opera Turandot, a work teeming with extraordinary invention, animated by the quirky fecundity of that amazing brain.

Bisengaliev is ever bit as impressive live as he is on disc. The technique is staggering: he strides through the most taxing passages as if he were doing nothing more difficult than scratching the back of his head. And he has considerable stage presence: at thirty-three years old, he is what I imagine does duty as a pin-up in Kazakhstan, with dark, striking good looks, far more oriental than Russian, reminding one of how far east the Soviet empire used to reach, a thought confirmed by the accent that colors his English. He is of medium height, but powerfully built, which may account in part for the strength of his tone: his playing suggests the forceful, heroic manner that is supposed to have characterized Ysaÿe's playing. In person, though, Bisengaliev is easy-going and relaxed, mild in voice, polite in manner, unemphatic in gesture. We chatted after the concert over a glass of wine as his four-year-old daughter, Aruhan (who in a couple of decades will obviously be a beautiful woman), played around the legs of her affectionate father. I asked first about his background.

"I began when I was six, in the special music school in Alma Ata, and studied there for eleven years. There was a very strong connection there with the Moscow school of violin playing and chamber music. And I come from a musical family. My dad, Samet, is a very good folk-music player, on the dombra; in fact, he's a virtuoso on it, and has recorded some kui [an instrumental piece of folk-music] on the Melodiya label. My mum is a really lovely amateur singer. And they brought up many professional musicians. My little sister is a pianist, a very good accompanist and teacher. My little brother is a cellist. So I have loads of nephews and nieces playing in the same school! And I had a brother (unfortunately, he died five years ago) who was the leader of the Kazakh State Symphony Orchestra; he was a graduate of the Moscow Conservatoire. I too went to Moscow from Alma Ata, studying with Valeri Klimov and Vladimir Belinky. I continued with Valeri Klimov in post-graduate before going back to be a soloist in the Philharmonia in Alma Ata, though I also stayed on in Moscow with Goskonzert. So I had a few years in Russia, until I met my wife Stina."

That Stina is English explains why Bisengaliev is now based in England; that she is the principal flautist in the orchestra of Opera North further explains why that base is in the unlikely location of Otley, outside Harrogate, in Yorkshire, many miles from a major urban center with a thriving musical life.

"My first recordings were with Melodiya. The Marco Polo/Naxos connection came about more or less by chance. In 1979, my first year in England (I was just married to Stina), I played with a semi-pro orchestra, the Hallam Sinfonia, in Sheffield. It happened that David Denton was there. He really liked my playing, and came back and asked if I would like to record for Marco Polo. Within half a year I was recording for them, starting with a disc for Naxos with the Lalo and the Polish National Symphony Orchestra." In 1992 he recorded his first recital disc for Naxos, of virtuoso showpieces by Wieniawski (8.550744), released two years later to understandable critical acclaim: the playing is blisteringly good. And since our interview he has recorded the two Wieniawski Concertos and the Faust Fantasy with Antoni Wit and, again, the Polish National Radio Symphony (Naxos 8.553517) .

But I am getting ahead of myself. Was the Brian Concerto also David Denton's idea? "Yes, a little bit later. He proposed that I learn this concerto. For a long time it was on and off. It took a long time to get the right orchestra, and also it was not an easy concerto to learn, so it took a little while. But we did record it within a year-and-a-half of the initial proposal, with the BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra. And now that I have learnt it, I would like to play it in as many concerts as possible. It was quite a challenge, this concerto, and I found it to be probably the most difficult I ever played. But the time I spent learning it, quite a long time, was really interesting. And I did enjoy the recording. It is a work which is really growing on me. Every time I play it, learning it or going through it with an orchestra, I find it more and more attractive, and I find more and more in the violin part and in the orchestra – it's really interesting music. I think it will find a way through, to become one of the major concertos, to find itself in a row with the best concertos of the twentieth century; it seems to concentrate everything that's best of what the twentienth century has given to us." I offer my five cents' worth: that it is certainly the finest British violin concerto written this century, pace the Elgar, Walton, Britten and anyone else. Bisengaliev immediately agrees: "Yes, I am sure of it. It's not just tuneful, not just romantic – it has everything the twentieth century produced."

Bisengaliev's most recent recording – of the Joachim arrangements for violin and piano of the Brahms Hungarian Dances and an Andantino and Romance by Joachim himself – has just been released on Naxos (8.553026), immediately after his first appearance in the Carnegie Hall. Bisengaliev explains that his recording offers those transcriptions as Joachim wrote them. "In one previous recording I know, by Aaron Rosand, the violin part is simplified. I understand him: he wanted to make it more attractive, more flush. I found a copy of the Joachim violin part, in which some of the numbers are very difficult to play. So I play the completely original version. At least, I think I manage to do that! It's the first time all twenty-one dances have been recorded as written. It's very important to bring forward the original version as nobody has yet recorded it. The same is true of the Havergal Brian: I put everything back that he wanted to be heard."

Further plans? "Well, after the Wieniawski Concertos and the Faust Fantasy, I plan to do an album of Sarasate showpieces, with John Lenehan, my duo partner. Then I hope to do some Samuel Coleridge-Taylor. Then there are many other concertos I'd like to record, like the Vieuxtemps. #4 and #5 first. I should do all of them, but there's always something more urgent to record. I also have to finish a series of recordings of Charles de Bériot, which I have started with the Ukrainian National Symphony Orchestra; I am recording #2 to 7, six concertos, since I think Takako Nishizake has recorded the rest." (There are ten altogether.)

Bisengaliev is very obviously a man with an open mind, so I seize the opportunity to throw an idea at him: has he thought of coupling the Violin Concerto of the Scottish composer Ronald Stevenson (whom I interviewed in Fanfare 19:2) with his Scots Suite for solo violin? I explain something of the Concerto's background: commissioned by Menuhin, who conducted the (so far) only performance with the Chinese violinist Hu Kun, the work is subtitled "The Gypsy" in hommage to George Enescu, to whose memory it is inscribed; it is an encyclopedic exploration of the world's violin styles, an extravagant and enjoyable confirmation of Stevenson's interest in "world music". I soon realise that with Bisengaliev, who has been leaning forward attentively, I am pushing on an open door. "That's very interesting. I like a challenge. I don't mean in the technical sense; I mean I like to try to make everything as good as possible. I just received another piece by Havergal Brian, the Legend for violin and piano. I want to play it in my Carnegie Hall debut, which will probably be the first time it is played there – I like giving premières."

In the event, Bisengaliev and Lenehan didn't have time to rehearse the piece for Carnegie Hall, though he now plays it regularly in recital and has scheduled it for a Wigmore Hall concert in London. The New York Times did him proud nonetheless: Allan Kozinn's review talked of his "opulent, appealingly varied sound," "exquisite delicacy and warmth" and "impressive fleetness" in the Brahms Third Sonata. That raised, after the event, an interesting point: all we had talked about so far in our interview were out-of-the-way-ish composers and repertoire; for all their commanding strengths, the Brians and the Stevensons, even the Vieuxtemps, are hardly centre-stage in the average's listener's experience. Didn't Bisengaliev nuture ambitions for more mainstream stuff – the Brahms Concerto, for example? "Well, I have never managed to play the Brahms with an orchestra. I know the Concerto, but every opportunity seems to slip past me – it's always Tchaikovsky, Sibelius, Bruch and so on, but never Brahms, even though it's a very popular concerto. It's just my karma, probably! I am doing the Bruch with the English Chamber Orchestra. But at the moment I have so many plans that I have to tackle them little by little. There are several Kazakh composers who have written especially for me. And there's a really nice piece by Mikhail Pletnyev." This news surprises me: so Pletnyev is not only a brilliant pianist and highly respected conductor, he's also a composer? And he's not a Kazakh, is he? "No, he's Russian. But he was a very good friend of my brother; they studied together. He has written a fantasy on Kazakh themes, for violin and big symphony orchestra; he and my brother played it with the Leningrad Phil. I'd like to play that somewhere in England – it is such a lovely piece and includes all the best Kazakh tunes. But although I'd like to do as many things as possible, I'd also like to do them as well as possible."

I suspect he'd find it difficult to do them badly.

Copyright © 1996/1998, Martin Anderson