The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Lawes Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

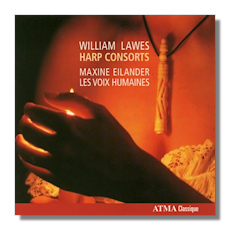

William Lawes

Harp Consorts

- Consort #1 in G minor

- Consort #2 in G minor

- Consort #3 in G Major

- Consort #4 in D minor

- Consort #5 in D Major

- Consort #6 in D Major

- Consort #7 in G Major

- Consort #8 in G Major

- Consort #9 in D Major

- Consort #10 in G minor

- Consort #11 in D minor

- Duo for Guitar and Harp

Maxine Eilander, harp

Stephen Stubbs, theorbo and guitar

David Greenberg, Baroque violin

Susie Napper, Margaret Little, violas da gamba

Les Voix Humaines

Atma Classique ACD2-2372

William Lawes (1602-1645) is one of those composers whose light is effectively hidden under all sorts of bushels. There is the bushel of confusion: his music is often lumped with that of his elder brother, Henry. The bushel of his death: William Lawes was shot in the English Civil War by a Parliamentarian solder (Lawes was a Court composer). And the bushel of obscurity: we have no reliable or substantial biography of Lawes: the most recent study, by M Lefkowitz, is 50 years old. Yet his music is distinguished, beautiful, technically accomplished, original and very fetching. And, mercifully, recordings of it are being added to the catalog with pleasing regularity.

The eleven Consorts for harp, bass viol, violin and theorbo are known as "The Harp Consorts". They are all to be found on this excellent CD from Dutch harpist Maxine Eilander with Les Voix Humaines. They're grouped according to key: three Consorts (numbers 3, 7 and 8) in G Major; two (4 and 11) in D minor; three (5, 6 and 9) in D Major and three (1, 2 and 10) in G minor. Track 12 is Lawes Duo for guitar and harp. Unsurprisingly this is the first complete recording of the Consorts: they're of a genre that had few discernible precedents: just think of the combinations of instruments! The dismantling of musical life (in the Royal Court in particular) by Cromwell and the changing tastes and currents at the Restoration in 1660 saw to it that there was nothing like it after Lawes' work.

But, as the musicians presenting this persuasive and energetic music clearly understand, the form is not an oddity. There is as much musical integrity in this music as in, say, the unusual combination which Messiaen employed in his Quatuor pour la fin du temps, say, or Bartók in the Music for Strings, Percussion and Celeste and it behooves the serious listener to set aside any other reaction than one which accepts the textures and timbres which Lawes chose to work with.

Of course the idea of the Mixed Consort (wind and/or plucked instruments in addition to members of the viol family) was well established by the time Lawes was working. What makes these unhurried and somewhat introspective works by Lawes stand out, of course, is the prominence of the harp. It's used to convey much of the melody, excitement and thematic pathfinding. In his accompanying essay on the way this recording was built, Stephen Stubbs speculates that the most likely instrument to have been used in the performances of these Consorts is actually the Irish harp, commonly used in Celtic folk music – and thus likely to have "resonated" (no pun intended) ill with those in England who resisted and resented all things Popish!

By the same token, the rôle of the bass viol is chiefly that of subtle and virtuosic ornamentation of the harp's and violin's melodic invention, although in certain movements it vies with the harp for melodic dominance. And, Yes, the violin had by now emerged as a leader too – particularly in the dance movements. The theorbo was Lawes' own instrument; but insufficient detail existed in the score for Stubbs to do other than effect a likely reconstruction of the way it interacted with the other instruments, being appropriately mindful of the influence exerted on the music of Court (as indeed on many other aspects of Court life before the Civil War) by the French and French aesthetics. But the instrument was always an equal partner.

Indeed, for such an unusual combination of instruments, Lawes achieves a remarkably unified and pleasing sound. No one instrument outshines the others; yet the individuality of each is preserved. Attention to this delicate balance – not compromise – is one of the successes of this CD: listen to the way in which melody, texture, tempi and movement are all supported and enhanced by the soloists playing as soloists in a modern string quartet do in the middle movements of the third Consort [tr.3], for example. It has as much wholeness and unity as a Haydn scherzo.

So the trick is to approach this wonderfully communicative music for its warmth, its unselfconscious depths (listen to the end of the 10th Consort [tr.9] for a precursor to the "Art of Fugue"!) and forays into quite personal expressiveness. To enjoy the interplay of sounds without "dueling". And to try hard not to lament which directions this neglected and extremely gifted composer would have taken had he not died when he did. The recording is first class, close, rich and sonorous without adding spurious resonance where it really is the precise, subtle, intricate yet robust lines of the melody that make this music so attractive. Attractive almost as if it were lute lines enhanced by the voice from the 1580s or 90s.

The musicianship is first class – as would be expected. Every nuance is respected; every change in tempo has a reason; every ounce of humor and pathos is weighed and conveyed; every delight (the opening of the fourth consort [tr.4], for example… pure sunshine) laid bare but not overplayed. If this seems out of the ordinary as "chamber" music, it is substantial and pleasingly intricate. And it has substantial appeal as such. If your interest is in mid-seventeenth century British music (of which there is not a huge amount) this CD is a "must" – particularly since no other recording exists. But for an hour of sophisticated, sonorous and gently challenging music for strings expertly played, the Lawes Harp Consorts will prove satisfying in the extreme. Recommended without hesitation.

Copyright © 2009, Mark Sealey