The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Thompson Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

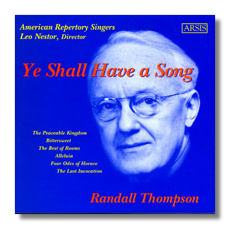

Randall Thompson

Ye Shall Have a Song

- The Peaceable Kingdom

- Bitter-Sweet

- The Best of Rooms

- Alleluia

- Odes of Horace (excerpts)

- The Last Invocation

American Repertory Singers/Leo Nestor

Arsis CD103

Summary for the Busy Executive: Fine performances of American classics.

Randall Thompson constitutes an odd case in American music. Quite prominent in his own day, he has faded from most serious discussions and almost all concert programs. The reaction against him seemed to set in after the Second World War, when most tonal composers – including such lights as Walter Piston, Roy Harris, and Aaron Copland – began to look old-hat, washed-up, and even corny. After all the years spent building a specifically American modernism, younger composers began to look toward Europe and southern California, the bastions of Arnold Schoenberg's twelve-tone method. We no longer wanted to be American, but international and classic. By the Sixties, professional schools simply ignored a large body of very fine work. Fortunately, enough composers of genius basically wrote the way they wanted to, so that now a fairly healthy eclecticism has become the rule. We still have committed serialists, but we also have minimalists, neo-Romantics, third-stream, and so on, all getting performances and recognition. However, we don't have many opportunities to rummage through the locker of the rather recent past. Performances of modern music (ie, anything from Pétrouchka on) tend to run to premières and near-premières. American music other than George Gershwin, Copland, and occasionally Charles Ives and Leonard Bernstein makes up an even shorter list. Thompson seemed to see this coming. Beginning in the Fifties, he withdrew from all professional venues and concentrated on writing for amateurs. One of the great composition and orchestration teachers (he, Roger Sessions, Howard Hanson, and Piston essentially created the American academic curriculum), he always had technique to burn. Now he put it in the service of church and college choirs and community ensembles. He never looked back.

As a result, his music stayed alive among amateurs. The Last Words of David, the Alleluia, The Nativity According to St. Luke, Frostiana, and the sets of "sacred songs" for chorus are still sung. As an unfortunate result, however, many professionals believe that Thompson is a "church choir composer" and have little idea that a great deal of music exists for them, and many amateur groups fail to do justice to some of the repertoire. Thompson composed in all major genres, with three symphonies, two string quartets, and at least one opera, among other things. At his best, I find him an American equivalent of Dvořák – great technique allied with early American folk music, particularly that of New England and the Appalachians, as the spring of melody. Of his symphonies, I find his second the most inspired. Bernstein (a Thompson orchestration pupil) has a killer version of this on Sony 60594.

This disc collects some of the a cappella choral works. Most of it, to judge by the dedicatees and performers (G. Wallace Woodworth, Archibald T. Davison, even Elliot Forbes), comes from the WASP hive of Harvard, where Thompson taught for decades. Thompson's choral music can be easy or hard, but it all at least "sounds." This was the first impression of his music I had as a high-school chorister (we mangled the Alleluia, but at least we got through it). Furthermore, he can get a very full texture with the fewest possible notes and without compromising voice-leading. According to Harvard luminary Elliot Forbes's liner notes, the Italian composer Gian Francesco Malipiero had encouraged Thompson to study the masters of the Italian Renaissance, which the young composer did, apparently to great profit. This led to a technique that could do anything and yet didn't rub a listener's nose in the composer's contrapuntal brilliance. Thompson's Mass of the Holy Spirit, for example, contains all manner of canon, but its communion with the listener impresses most of all. This work, by the way, needs an ace choir.

Thompson's great "hit," the Alleluia was composed for Tanglewood in an amazing four days. Technically, it's a study in declamation and rhythmic counterpoint, with the single-word text, "Alleluia," accented several different ways in different parts of the measure. Forbes points out that Thompson wrote the piece in 1941 just after the fall of France and it's hardly an ode to joy. In fact, it goes through many moods, beginning raptly and tenderly, moving through dark and anxious moments before breaking through to cascades of alleluias, like the swooping and soaring of larks, and ending with a quiet "Amen." In fact, its rhetorical movement reminds me of a sermon. As I say, an amateur choir can get through it. A great choir willing to accept its challenges, however, reveals something seven kinds of wonderful. It deserves every bit of its popularity.

"Bitter-Sweet" came fairly late in Thompson's career. It sounds like "bittersweet," but the hyphen makes all the difference. "Bittersweet" connotes sentimentality, whereas Thompson composed the chorus in response to the death of his beloved granddaughter Katie. Forbes notes that it's one of the composer's most personal works, and I agree. It's quite out of the run of the amateur works to which Thompson had been confining himself. The harmonic palette darkens and more dissonance comes in. The bitterness of pain clashes with the hope of consolation as it sets a George Herbert poem, and it takes good performers to move from one to the other without stumble or breakdown. Consolation never quite arrives. I find the ending uneasy still.

"The Best of Rooms" is an example of Thompson's "mirror writing" – ie, where the upper and lower parts move in opposite directions – if, say, the soprano line rises, the bass line falls. It's a technique Thompson keeps returning to. Again, if someone didn't point it out, most listeners wouldn't notice.

"The Last Invocation" takes the Walt Whitman poem from Whispers of Heavenly Death. Thompson wrote it in his twenties, before receiving his fellowship at the American Academy in Rome (Hanson and Sessions also worked there). It's a solid job, but unfortunately I hear William Schuman's spare setting as I read the words. As far as I'm concerned, Schuman owns this text.

The Odes of Horace, originally five with a sixth added about thirty years later, comprise the earliest fruits of Thompson's study of the Italian Renaissance and Mannerist composers. The CD presents four of them. Early, pre-Baroque Monteverdi and de Wert seem the models, although Forbes makes a case for late Monteverdi as well. This is text-setting of great sophistication and resource, and yet again one is aware mainly of the expressive power of the music.

With The Peaceable Kingdom, we begin to talk about an American choral masterpiece. Thompson wrote it at a time when American composers had begun to check out Colonial and Federal music, particularly the collections of The Continental Harmony and The Sacred Harp. From this period, we get Henry Cowell's series of Hymns and Fuguing Tunes, Virgil Thomson's 4 Southern Hymns and Symphony on a Hymn Tune, and (slightly later) Schuman's New England Triptych. Everything about Thompson's work is first-rate, from the immediate source of his inspiration ("The Peaceable Kingdom," by the early American preacher and primitive painter Edward Hicks), to his choice of texts, to his musical models from The Sacred Harp, to the actual composition. I've known the work for about forty years and bought the score before I reached twenty, but Forbes's notes to the piece tell me things I didn't realize about the work and show again the subtlety of Thompson's technique. The notes particularly help identifying the motifs that unify the entire cycle.

The work begins with "Say ye to the righteous," which sets two-part writing for the men against full chorus, an opposition which reflects the contrast between the blessings on the "righteous" and "woe" on the "wicked." The music moves from rapt, pastoral contentment (an incredibly beautiful tune, perfectly harmonized) to loud outcries and back again. Thompson carries the dichotomy throughout the work. "Woe unto them," "The noise of a multitude in the mountains," and "Howl ye" paint the punishment of the wicked in effective terms without recourse to a whole lot of notes, but to a full toolkit of choral techniques. "Woe unto them" plays with odd meters to capture a conversational declamation, but with no delving into choral recitative. A steady pulse beats throughout the number. In "The noise of a multitude," Thompson uses rhythms apparently derived from Igor Stravinsky's Le Sacre. "Howl ye," which divides the choir in two, makes much of antiphony and fugato. The work reaches its peak of intensity here, and paradoxically on a pure major chord for both choirs, fortissimo on the word "howl." "The paper reeds by the brook" (often excerpted) follows with a tender quasi-chorale in Thompson's mirror writing. It manages to evoke other Biblical laments as well, notably those of Jeremiah. This is the fate of the wicked: "The paper reeds by the brook, by the mouth of the brook, and everything sown by the brook shall wither, be driven away, and be no more." For here on, Thompson prepares us for God's promise to the righteous, heard in the first number: "It shall be well with them, for they shall eat the fruit of their doings." "But these are they" has a magical section to the words: "The mountains and the hills shall break forth before you into singing, and all the trees of the fields shall clap their hands." That last image is one of my favorites in the entire Bible, and Thompson rises to the occasion with word-painting brilliantly simple and evoking the rustle of leaves, the wind, and echoes from the far hills. "Ye shall have a song" – the finale which gives the CD its title – alternates between the women's and men's sections. The women's timbre conjures up for me yearning and hope, the men's the mystery of God's promise. The movement is largely chordal, with delightful passages of imitation and word-painting on the words "as when one goeth with a pipe to come into the mountains of the Lord." Thompson constructs not one, but two long climaxes, the second of which concludes the entire cycle with, in Forbes's words, "a majestic cadence of overpowering intensity [to bring]… the work to a triumphant conclusion." Certainly, that's how it works on me, even after all these years.

The work has suffered from amateur recorded performances. Nestor's group is undoubtedly the best choir to date to tackle this music on record. It is a very fine group indeed, very well trained, if not the acme of choral singing. Some pitch problems crop up here and there, particularly among the tenors, but the group has a yummy tone and a fabulously suave musical line. The group is based in Washington, D.C., and those of you lucky enough to live in the area should look for their concerts. As for me, I can't wait to hear their next disc.

Recorded sound is a shade too reverberant, but acceptable.

Copyright © 1998, Steve Schwartz