The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Handel Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

DVD Review

DVD Review

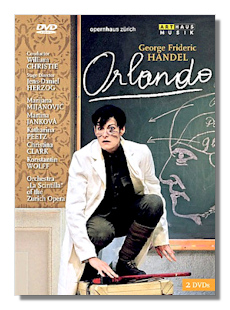

George Frideric Handel

Orlando

- Marijana Mijanovic (Orlando)

- Martina Janková (Angelica)

- Katharina Peetz (Medoro)

- Christina Clark (Dorinda)

- Konstantin Wolff (Zoroastro)

Orchestra "La Scintilla"of the Zürich Opera/William Christie

Arthaus Musik 101309 2DVDs 155:00

Orlando (1733) is one of three operas that Handel based on Ariosto's Orlando furioso. (The other two are Ariodante and Alcina.) The title role was composed as a vehicle for the castrato Senesino. The plot is the usual Baroque entanglement of love both requited and unrequited. Orlando, a great hero in Charlemagne's army, has been undone by love. Angelica, the Queen of Cathay and his former lover, now loves the African prince Medoro. Medoro, who once promised love to the shepherdess Dorinda, now requites Angelica's love. In other words, we have two spurned lovers – Dorinda, whose reaction is seriocomic, and Orlando, whose reaction is to fall into madness. Dorinda is clever enough to fend for herself, but the magician Zoroastro must put Orlando back together again. This he successfully does, and Orlando is restored to his former military glory at the end of the opera.

Director Jens-Daniel Herzog has set this 2007 production from Zürich in a sanatorium around the time of World War One. Orlando is a decorated hero who has come for treatment, and Zoroastro is the sanatorium's head doctor. Dorinda is a pretty nurse. Medoro and Angelica both are given the appearance of high society types. Sometimes this restaging is at odds with the libretto (why would a nurse be singing about goats and lambs?), but it is clever and it gets the point across: love can make us lose our reason. Herzog sexes it up a bit: there is enough groping and other suggestive behavior here to make putting the kids to bed early a good idea. There's also a little violence: in the last act, Dorinda gives Angelica a bloody nose. (It is unpleasant to watch Angelica sing her beautiful aria "Così giusta è questa speme" looking like she just went three rounds in the ring with Mike Tyson.)

The most important thing, though, is the music and the singing. Although it is comparatively light on bravura arias, Orlando is one of Handel's most appealing scores. It sticks in the memory not for being exciting but for being utterly gorgeous. For example, the trio for Medoro, Angelica, and Dorinda that closes act I is an almost Rosenkavalier-like example of the joys that can result from three women's voices intertwining. (Even in 1733, the male role of Medoro was sung by a woman, not by a castrato.) Another highlight of the score is the mad scene for Orlando, which closes act II. Handel's use of disjointed phrases and uneven rhythms aptly depicts the disorder inside the hero's head.

Physically, contralto Marijana Mijanovic is a convincingly male Orlando, although her features are more boyish than maturely masculine, and she scowls and grimaces throughout the opera. Her lower register is similarly masculine. Unfortunately, her singing, while generally very good, is the least appealing here. There is not enough variety in the shading and color of her tone, and her performance of the more agile passages sometimes takes on a distracting clucking quality. Katharina Peetz also doesn't do as much with her voice as she might, although, with her little moustache, she looks like a reasonably caddish Medoro! Sopranos Martina Janková and Christina Clark are absolutely delightful, though. I haven't encountered either of them before, but I will keep my ears open for both of them. The former has a secure, silvery tone that simultaneously excites and hypnotizes, while the latter seems to be following (adorably) in the footsteps of the young Kathleen Battle. Her basic tone is innocent and girlish, but not immature, and watch out: Clark can move from tearfulness to vengefulness in very little time. She is an accomplished actress, and a voice like hers would make any lamb glad to follow her. Konstantin Wolff, the sole male in the cast, cuts an impressive figure as Zoroastro, and he sings with the necessary authority. Only in his florid final aria does he seem a little strained, but the charisma of his portrayal wins out.

William Christie has conducted this opera in several different places, and his performance here gives the score's beauties and its drama their due. The orchestra makes a few sour noises, but by and large they contribute positively to the evening's success.

The first two acts are on the first DVD, and the third act is on the second DVD. There is no bonus material. Sound quality (in the three usual formats) is top of the line, and the 16:9 visuals are similarly excellent. By often moving in close, video director Felix Breisach keeps home viewers involved in the action – without being intrusive, however.

After Giulio Cesare, the next Handel opera one might want to have on DVD is Orlando, and this production from Zürich makes an excellent case for it!

Copyright © 2009, Raymond Tuttle