The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Beaser Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

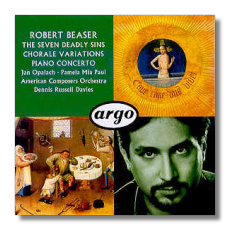

Robert Beaser

- Chorale Variations

- The Seven Deadly Sins 1

- Concerto for Piano and Orchestra 2

1 Jan Opalach, bass-baritone

2 Pamela Mia Paul, piano

American Composers Orchestra/Dennis Russell Davies

Argo 440337-2 DDD 77:06

Reissued as Phoenix CD162

Amazon

- UK

- Germany

- Canada

- France

- Japan

- ArkivMusic

- CD Universe

- JPC

I really should like this music more. It's squarely within the modern, post-Romantic tradition. It's got craft up to its eyeballs. It doesn't look for the easy path to a listener's soul. But I turn on the Chorale Variations, and five minutes into it, I pick up a book. The next thing I know, I'm listening to the next selection. So I let loose with an expletive deleted and reset the CD player. Eight minutes later, I get enormously engrossed with the TV Guide crossword puzzle (the issue itself is several years old), look up at the CD timer display (wow! 7 minutes really flew), tell myself I really have to buckle down this time, but since I know the first 8 minutes, decide to catch up cataloging my new CDs. And so it goes. Up to the time of writing this sentence, I have no idea how the Variations end. Beaser has a real gift for creating bright, unusual orchestral sound. What he doesn't seem to have is an interesting thematic idea – strange, since his chorale theme consists of fourths and fifths, usually dramatic attention-grabbers. I have no clue why I can't connect.

My haplessness continues with The Seven Deadly Sins. Again, great sounds from the orchestra can't keep my mind from wandering, nor can Anthony Hecht's splendid texts. The choice of Hecht points up Beaser's canniness and literacy. Hecht, one of our most musical poets (John Holländer's another), isn't that well known. I've always thought composers missed a bet by not going to his Hard Hours. Well, Beaser has found the book, but he hasn't served Hecht particularly well. The tunes aren't necessary to the words nor do they expand emotionally on the words. The most Beaser rises to is a genteel wit. If we compare Beaser's work to Weill's acerbic masterpiece of the same name, Beaser's bleaches out. Weill grabs you from the first and never lets go. Beaser taps you on the shoulder, coughs politely, and proceeds to bury you in musical bromides. You start to long to talk to the really interesting insurance salesman about updating your coverage.

Beaser intends a virtuosic, heroic piano concerto. In fact, it's kind of a post-modern concerto, in that echoes and not-quite echoes of earlier works come in almost at the subliminal level: Copland's Piano Concerto, Barber's Piano Concerto, Gershwin's Concerto in F, Bernstein's West Side Story, just to name a few, flit across the listener's consciousness. The first movement certainly delivers its promised punch. If it has a fault, it's that there are too many ideas and one idea seems as good as the next. In spite of Beaser's prodigal supply of variation and development, the material doesn't really shape the piece. Rather, our expectations of an opening concerto movement do. We get the climaxes and the cadenzas in the right spots, but not the sense of a tale well-told. If he had a better sense of hierarchy, he could have used half the material to greater effect.

The slow movement continues along the same lines, this time opening with the initial theme to the slow movement of Beethoven's Violin Concerto. Beaser never quotes directly. It's kind of like looking at a "celebrity double" or staring at a total stranger who resembles too much somebody you used to date. We also get thematic references to the first movement. It adds up to mighty little, I'm afraid, especially since the composer has from the start put himself against one of the greatest, and least fussy, movements in the concerto literature.

The last movement gives us great drive as well as a little Barber here, a little Ginastera there. But where is Beaser? I realize that, even though the music has at times gotten my rocks off, I have no idea where the core of Beaser's music lies. Either nothing lies inside or it's buried under layers of what amounts to musical euphuism. It's like meeting a man born without any identifying marks, including fingerprints. If this is what's touted as post-Romantic, we are definitely in trouble. How could anyone mistake a rhetorician like Beaser for a poet like Barber?

The performances, under Dennis Russell Davies, are stunning, and Argo's engineering is loving, bright, and rich. Pamela Mia Paul takes on the finger-busting piano writing and earns the role of hero. After all this, I, believe it or not, haven't made up my mind about Beaser, but then the composer hasn't given me much to go on. If anyone manages to make contact, let me know.

Copyright © 1998, Steve Schwartz