The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- J.S. Bach Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

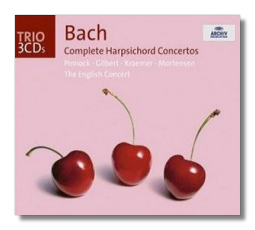

Johann Sebastian Bach

Complete Harpsichord Concerti

- Concerto for Harpsichord in D minor, BWV 1052

- Concerto for Harpsichord in E Major, BWV 1053

- Concerto for Harpsichord in D Major, BWV 1054

- Concerto for Harpsichord in A Major, BWV 1055

- Concerto for Harpsichord in F minor, BWV 1056

- Concerto for Harpsichord & 2 Recorders in F Major, BWV 1057

- Concerto for Harpsichord in G minor, BWV 1058

- Concerto for 2 Harpsichords in C Major, BWV 1061

- Concerto for 2 Harpsichords in C minor, BWV 1062

- Concerto for 3 Harpsichords in D minor, BWV 1063

- Concerto for 3 Harpsichords in C Major, BWV 1064

- Concerto for 4 Harpsichords in a minor, BWV 1065

- Concerto for 2 Harpsichords in C minor, BWV 1060

Trevor Pinnock, Kenneth Gilbert, Lars Ulrik Mortensen, Nicholas Kraemer (harpsichords)

The English Concert/Trevor Pinnock

Deutsche Grammophon Archiv 471754-2 3CDs 199:27 ADD/DDD

Summary for the Busy Executive: Sprightly.

Bach, as far as I know, is the first composer to write a concerto for harpsichord. Vivaldi and Handel had written organ concerti, but Baroque composers generally regarded the harpsichord as a "utility" orchestral instrument, something to fill in harmonies. Not even Vivaldi, one of the most brilliant and inventive orchestrators in music, saw the potential of the instrument as a solo superstar on the order even of, say, the bassoon.

Bach arranged all his harpsichord concerti from ones for so-called "melody" instruments – usually violin or oboe – mostly his own concerti, but in one case a Vivaldi concerto for four violins. Almost all the rearrangements are re-imaginings of the music, by necessity. After all, a harpsichord plays more simultaneous lines than an oboe. Yet, if you didn't know better, you would think them original compositions. One can also consider his earliest concerted work highlighting the harpsichord – the fifth Brandenburg – as a harpsichord concerto, and it must have astonished its first hearers, as the keyboard gradually rises out of the orchestra and eventually monopolizes the musical interest – sort of like watching a geriatric suddenly bust a move. The Brandenburg, however, stands apart from the recognized canon of Bach's harpsichord concerti, which all come from later in the composer's career. Bach's relations with the Leipzig town council had plunged from habitually pissy to horrific. From the beginning, they considered him a mediocrity, a judgment which startles us today. They sneered at his music as "learned," in much the same way you now hear people scoffing at "intellectual" music. In my experience, you actually have to know something to be this blinkered. Most inexperienced listeners, while they might be bored, nevertheless don't normally get so specific. Furthermore, the Leipzig burgers tended to favor the newer, simpler pre-classical styles of the eighteenth-century Bright Young Things, like Quantz or even W. F. And C. P. E. Bach. So, in a way, these worthies showed their musical sophistication. However such negative criticism, often accompanied by dogmatic delivery, usually has very little to do with anything other than self-flattery. It seldom shows much understanding of the work it criticizes. At any rate, Bach had been effectively replaced at the main Leipzig church, although he continued at one of the others. To fill in time and to supplement his income, he took over the directorship of the Leipzig Collegium Musicum, a band of, I believe, mostly amateurs and created these concerti for their repertoire. Compared to the orchestral writing in the Brandenburgs or the orchestral suites, for example, the ripieno demands a lot less from its players. The harpsichord – or two, three, or four harpsichords – provides the fireworks.

The first recording I heard was an old Nonesuch LP of the entire set. I remember none of the performers (Ristenpart?), only that the music, with the exception of the concerto for four harpsichords, failed to impress me – and that was, at bottom, Vivaldi. I disliked the set so much that it took me about ten years to hear another – this time, Raymond Leppard and friends on Philips. Leppard hadn't recorded all the concerti. He left out some of the more obvious arrangements, like the one of the fourth Brandenburg. However, Leppard, one of the great harpsichordists of the century, possessed an aural imagination and rhythmic élan unmatched by anyone but Landowska. He also happened to conduct Baroque music incredibly well, if not with "historical" correctness. He made it sound both rich and buoyant, indeed joyful. To this day, Leppard's set remains my standard, its only disadvantage its lack of completeness. Some of these recordings have been re-r eleased on a Philips two-fer, well worth seeking out.

Pinnock, one of my favorite musicians, may lack the sumptuousness of Leppard, but he still has plenty of bounce. Indeed, he swings. The sound of the orchestra is leaner as well, and attacks have bite and purpose. Everything moves. The orchestra may not be as necessary to the success of these works as the soloist, but it's a nice bonus when the band engages the music in high gear. Everything here steps lightly and definitely. Most importantly, everyone steps with one mind, like a superb pair of dancers. The other harpsichordists fall in with Pinnock in the multi-soloist concerti, matching the energy of his line. The engineering creates a detailed sonic landscape which distinguishes one harpsichord from another, particularly helpful in the concerti for three and four keyboards. This recording stands in line just behind the Leppard.

Copyright © 2006, Steve Schwartz