The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

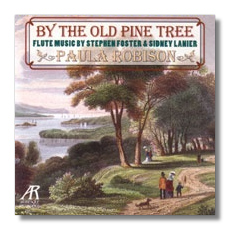

By the Old Pine Tree

Flute Music

- Stephen Collins Foster:

- Village Festival - 4 Quadrilles & Jig

- Anadolia

- Byerly's Waltz

- Rainbow Schottisch

- Jennie's Own Schottisch

- I Dream of Jeanie with the Light Brown Hair

- Oh! Susanna

- The Old Pine Tree

- Beautiful Dreamer

- Maggie by My Side

- Gentle Annie

- Where Are the Friends of My Youth

- Old Folks' Quadrilles: Old Folks at Home; Oh, Boys, Carry Me 'Long; Nelly Bly; Farewell, My Lilly Dear; Plantation Jig

- My Old Kentucky Home, Good Night

- Sidney Lanier:

- Blackbirds

- Wald einsamkeit I

- Wald einsamkeit II

- a Melody from Lanier's Flute

- Cradle Song

- Wind Song

Paula Robison, flute

Krista and Bennion Feeney, violin

Calvin Wiersma, violin

John Feeney, doublebass

Samuel Sanders, piano

Arabesque Recordings Z6679 DDD 53:36

Stephen Foster and Sidney Lanier are both regarded as cultural figures of the ante-bellum South, although only the latter was born and raised there. Both led short intense lives and tried to write music (in Lanier's case, poetry as well) that was intrinsically American.

Foster was born in the North, to a prominent family in Lawrenceburg, Pennsylvania, on July 4, 1826, the day both John Adams and Thomas Jefferson died. His first published songs of a folk nature were "Oh! Susanna" and "Old Uncle Ned." These were given for a pittance to W.C. Peters, a music publisher who went on to make at least $10,000 from them; Foster never saw another penny despite the songs' immense popularity. He then went on to write such standards as "My Old Kentucky Home," "Massa's in de Cold, Cold Ground," and "Old Uncle Ned." His initial deal with Peters was not atypical. He lacked a good business sense and was easily exploited by publishers. Foster ended up an alcoholic, living from one hastily written and quickly sold song to another. He died obscurely in a cheap New York City hotel on January 13, 1864 and was saved from a potter's field burial only at the last minute.

Along with Dan Emmett, Stephen Foster was the most prominent minstrel song composer in the 1850s and 1860s. Foster specialized in solo "plantation melodies" for the first part of the "Negro" minstrel show, while Emmett wrote the "plantation walkarounds" for the second, humorous in intent and performed by the entire company. Minstrel shows were always done by white performers in black face.

Foster didn't actually visit the South until 1852. He obtained his notions of African-American singing from minstrel shows and from observing Northern black church services. Songs like "Oh! Susanna" and "Old Folks at Home" were inspired by authentic black spirituals such as "Sometimes I Feel Like a Motherless Child." However, Foster removed the pain and despair, and instead wrote pleasant, sentimental melodies that could well have been used to make Northerners and Southerners alike feel good about the Old South, and make runaway slaves long for their good life on the plantation.

Sidney Lanier was born on February 3, 1842, in Macon, Georgia, to a well-to-do family. His father was a prominent lawyer, his mother came from a family of plantation owners. At the age of 19, he enlisted in the Confederate infantry; he served for almost four years and ended the Civil War in a Union prison in Maryland. Lanier's health, which suffered in the War, worsened in prison. He struggled with tuberculosis until the end of his brief life in 1881.

Throughout Lanier's life, poetry and music shared his attention equally. Indeed, several of his poems (such as "To Beethoven") are on musical subjects and some (such as "The Symphony") try to emulate music. His attempts to find an equivalent for music in the written word were unsuccessful. "The Symphony," like all of his poetry, is second-rate and virtually unreadable now. Lanier steeped himself in German writers and German romanticism. His writings are filled with an outdated chivalric tradition that appealed to the ante-bellum South.

In this excerpt from "The Symphony" (1875), he tries to bring the sounds of musical instruments to the printed page:

"And then, as when from words that seem but rude

We pass to silent pain that sits abrood

Back in our heart's great dark and solitude,

so sank the strings to gentle throbbing

Of long chords change-marked with sobbing -

Motherly sobbing, not distinctlier heard

Than half wing-openings of the sleeping bird,

Some dream of danger to her young hath stirred.".

And later in the same poem, Lanier writes:

"There thrust the bold straightforward horn

To battle for that lady lorn,

With heartsome voice of mellow scorn,

like any knight in knighthood's morn.".

While writing his poetry, Lanier pursued his career as a musician and composer. By all accounts, he was a superb flutist. In 1873, he auditioned for the Peabody Orchestra in Baltimore (later to become the Baltimore Symphony Orchestra). Lanier so impressed the director that he was made principal flutist, a position he held until 1878.

Only one of Lanier's musical compositions was published during his lifetime. Just recently, manuscripts of his works have been made available, so these are first recordings.

There are 28 selections on this new CD from Arabesque Recordings. Six are by Lanier, the remainder are by Foster. They range from quadrilles and jigs to simple flute melodies and renditions of perennials such as Foster's "I Dream of Jeanie with the Light Brown Hair." Lanier's "Blackbirds" is in the tradition of bird mimicry as later practiced by Ottorino Respighi and Olivier Messaien; it is a successful and charming work. Foster's quadrilles and jigs are old-fashioned and formal, with that same chivalric European air as Lanier's poetry. Their exuberance is constrained, just as such dances were tightly patterned. They could easily serve as background music for an epic about the Old South; close your eyes while listening and you can see hoop-skirted belles swirling around an old manse's ballroom.

Paula Robison and her accompanying artists bring a good deal of spirit to these pieces. This is a friendly recording, very listenable and not very challenging. Perhaps you shouldn't listen to it too closely - put it in the background while doing other tasks. At that level, it is quite pretty and ornamental. Robison puts a good deal of playfulness and bounce into the dance pieces. She brightens up music that would otherwise remain staid. I especially enjoyed the Foster dance pieces and the exhilarating rendition of "Oh! Susanna."

The six compositions by Sidney Lanier are performed in a pensive, meditational mood. (I noticed a marked similarity to Claude Debussy, who lived later, in France, in "Wind Song" - perhaps this is Robison's doing.) They are inward and contrast with the more worldly Foster pieces. It is good that Robison has rescued Lanier from an undeserved obscurity. Had he lived longer and put aside his poetry to devote himself exclusively to music, Lanier might have ended up with an important body of work.

This CD grew on me as I listened several times. I especially enjoyed the way in which Robison recast familiar melodies with buoyancy and enthusiasm. But if you listen too closely, you can hear the stiffness, the reserve, the arch quaintness of these pieces. All of Robison and company's artistry cannot conceal the formulaic compositional style that was becoming out of date even as Foster and Lanier were composing these pieces.

Stephen Foster and Sidney Lanier may have intended to compose a truly American music, but their pieces harken back to the European and would-be-European models that the ante-bellum South favored and imitated. For the real avatar of American music, listen to their great contemporary, Louis Moreau Gottschalk (1829-1869).

Copyright © 1996, Martin Jukovsky