The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

-

Britten Reviews

Bruch Reviews - Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

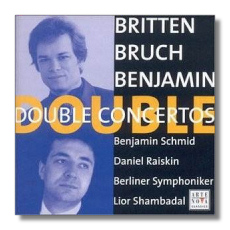

Double Concertos

- Arthur Benjamin: Romantic Fantasy for Violin, Viola & Orchestra

- Benjamin Britten: Concerto for Violin, Viola & Orchestra

- Max Bruch: Concerto for Violin, Viola & Orchestra in E minor, Op. 88

Benjamin Schmid, violin

Daniel Raiskin, viola

Berlin Symphony Orchestra/Lior Shambadal

Arte Nova 74321-89826-2 63:59

Summary for the Busy Executive: Mostly wonderful program; good performances.

From at least Vivaldi on, one finds a good number of double concerti, but not all that many for violin and viola. The problem stems from composers' attitudes toward the viola – an instrument that usually does little more than fill in harmony and texture – as well as the viola's range, which tends to bury it in the middle of things. The combination of violin and cello, for example, allows significant range overlap of the two instruments as well as a wider range than violin and viola and a more pronounced color contrast. One doesn't normally think of the viola as a powerful, individual orchestral voice, although one can readily cite composers who have created great roles for the instrument: Shostakovich, Hindemith, Walton, Mozart, Richard Strauss, and Rózsa among them. I, however, have always preferred the sound of a viola to that of a violin. I once tried to write a string quartet that eliminated violins completely – two violas and two cellos – before my professor made me revise it for the standard combo in the name of greater color variation. He was right, but you can see the lengths I was willing to go.

None of the three works here can claim a place in standard rep. Indeed, the Britten Double Concerto was discovered only relatively recently, in a kind of piano score with indications as to orchestration from the composer himself. Colin Matthews realized the score and claims that Britten's instructions were so complete that the score now is "virtually 100 percent Britten." Who knows? It certainly is a marvelous piece of music and a great addition to the Britten catalogue. He wrote it at 19, but a composer of any age should have been proud to have produced it. Schmid and Raiskin (who gave the German première) compete with Kremer, Bashmet, and Nagano on Erato 25502-2 (see a detailed review). Schmid and Raiskin's main virtue is their musical sensitivity to one another. In this, they are the equals of Kremer and Bashmet. Unfortunately, Shambadal and the Berlin play way too crudely. There's nothing out-and-out terrible and if you knew only this recording, you'd probably be satisfied, but compared to Nagano and the Hallé, the reading is one-dimensional. Nagano gets the piece to breathe and move like a living creature. Shambadal's account has all the vivacity of concrete.

Australian-born Arthur Benjamin received his training and made his career in England. His music has fallen almost completely under the radar. His artistic voice speaks with many accents from piece to piece – influenced by jazz, Caribbean music, Hindemith, Lambert, Stravinsky – and the lack of a strong individual profile may have contributed to his present obscurity. Nevertheless, everything is very well made, and much is beautiful. The Romantic Fantasy (though not, as the liner notes claim, written for or even premièred by them) came into relative prominence through the efforts of Heifetz and Primrose, who made two recordings: one in the late Thirties, shortly after Benjamin wrote the work, and one in stereo in 1964 for RCA. The LP, never, as far as I know, released on compact disc, introduced me to the piece. "Fantasy" implies an improvisatory structure, but Benjamin builds very sturdily, from a very small kit of ideas. The structure also shows a master planner, who can create convincing paragraphs and who has no trouble with unconventional forms. The Fantasy is in three, tightly-related continuous movements. Anyone who knows the Mahler Fourth will feel the little hairs on the back of his neck stand up at the opening horn call, whose notes repeat a major motif in the song about the "heavenly life." In fact, Benjamin got his theme from Arnold Bax, not Mahler. Indeed, much of the piece isn't Mahlerian at all. If it reminds me of anything, it's the Barber Violin Concerto, which comes slightly later, and I doubt that Barber had heard Benjamin or vice versa at the time. The similarities extend to the harmonic palette and to certain features of orchestration, including the somewhat unusual use of orchestral piano in both scores and a color emphasis on double reeds. If it doesn't reach the intensity of the Barber, it nevertheless sings as beautifully. The stereo Heifetz-Primrose is probably a classic recording, but I find a bit too schmaltzy, too concerned with the star power of the soloists (or at least one of the soloists). Schmid and Raiskin have the empathy, the weird radar of fine chamber players. They bring to the Fantasy great refinement. Again, however, the orchestra doesn't reach their level.

Max Bruch originally wrote his concerto for clarinet and viola. He arranged it for the present combo. Commentators make a big deal of the fact that Bruch composed this very Mendelssohnian work in 1911 and point to the hostile modern environment for such a work as contributing to its obscurity. I've always found this kind of argument a little specious (on both sides of the argument), since most people don't know and could care less about when a composer wrote a work. The valid question, as always, is how good the work is in itself. I happen to like a lot of Bruch's music, but this piece fails to rouse my attention. If the concerto has one non-recycled idea in it, then I missed it. The question of performance thus becomes pretty much de trop – a shame, because all the performers have a much firmer grasp on Bruch's idiom than on either Benjamin's or Britten's.

The sound is a bit dead, but the interest of the program should make up for it.

Copyright © 2002, Steve Schwartz