The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Lees Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

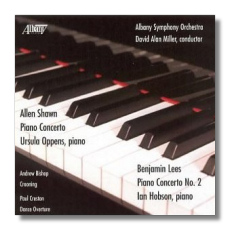

Benjamin Lees

- Andrew Bishop: Crooning

- Allen Shawn: Concerto for Piano *

- Paul Creston: Dance Overture

- Benjamin Lees: Concerto for Piano #2 **

* Ursula Oppens, piano

** Ian Hobson, piano

Albany Symphony Orchestra/David Alan Miller

Albany TROY441 73.55

Summary for the Busy Executive: Two piano concerti, no errors, one hit.

The Albany label has come up with yet another very interesting CD of American music. I'd not heard of either Bishop or Shawn before, so like any other collector, I welcomed the discovery. At least I've heard their music. I find Bishop far more interesting than Shawn.

One of my big ideas is that vernacular music – in all centuries but the Twentieth – has routinely invigorated art music. In the past one hundred years or so, many have regarded vernacular music as worthless, or even unclean. Witness the current tirades against hip-hop, for example. Sadly, this attitude occurred with the rise of American pop, one of the most vital and various vernaculars. Elliott Carter, for example, pays homage to Ives but avoids the culture that inspired Ives. Andrew Bishop studied at the University of Michigan with Bolcom, Albright, and Daugherty – all of whom have used American pop to give their music a shot in the arm. He's also worked in jazz orchestras. Crooning, as its title suggests, draws on the sound of big bands and big-band singers. It begins with a kind of Daugherty vamp, vivacious and slightly jittery. A solo violin begins to wail soulfully against the vamp. Little by little, the sound of the Nelson Riddle Orchestra on a ballad begins to intrude, and we have a conflict between the jumpy bit and the ballad. The ballad takes over more and more, and the motives that we've heard up to this point from everybody begin to coalesce into a melodic idea that seems the blueprint for "Fly Me to the Moon." The pop ideas exist on a rather abstract plane and jostle against ideas not pop at all. Bishop doesn't simply appropriate, any more than Bolcom does in, say, his second violin sonata. All in all, a very poetic piece, and the poetry is complicated.

Creston's Dance Overture comes from the early Fifties, sort of the tail end of the peak in the composer's reputation. Creston, an American original, belonged to no school and, indeed, largely taught himself how to compose. He has a voice instantly recognizable, although his music derives harmonically from French composers like Debussy and Ravel. Nevertheless, he sees those harmonies from a less-lush viewpoint. His rhythmic ideas resemble no one else's. Despite at least one very good symphony (his second), he comes across mainly as a great composer of light music – light not only in its lack of pretension, but in the brightness of its orchestral color and in its buoyancy. Dance Overture typifies him at his best, with jumpy little rhythmic cells coming together to create a larger, longer stride. Like the Bishop, this is eminently accessible music without condescension.

To me, the most interesting thing about Allen Shawn is that he is the son of the great New Yorker editor William and the brother of dramatist and actor Wallace. He's had a number of good teachers, including Kirchner and Boulanger, and a relatively successful career, with recordings, awards, and fellowships to his credit. This is the first piece of his I've heard, and I simply don't click with it. I know technically what's going on, but it fails to grab me emotionally. It strikes me as well-written and way too refined for its own artistic good – a genteel pastel. I yearn for even one cheap moment in the piece. I had trouble following it, mainly because I kept forgetting the main ideas, including a flute and oboe duet that has great consequences later on in the concerto. I had to write the ideas down before the work made detailed sense to me. This might mean that the ideas aren't very memorable in themselves and that no amount of repetition strengthens them. This is true of at least three of the movements, especially the first, which aims at brooding introspection (with shafts of light penetrating here and there). I liked the second movement (a scherzo, sort of) the best. Again, the material doesn't stick in the memory, but at least the movement has rhythmic life. It reminded me, here and there, of Bernstein's Age of Anxiety symphony. The slow movement, an homage to Mozart, rips off the manner of Ravel's slow movement in the G-major concerto, without the latter's melodic distinction. It occurs to me at this point that Shawn's music is mainly manner – or good manners. The finale exploits the material of the previous movements. Since that material failed to dent consciousness the first time around, it's unlikely that its recall will. Ursula Oppens's anemic, monochromatic playing and pallid, unimaginative way with a phrase don't help matters.

The weaknesses of Shawn's concerto come into immediate focus when you hear the Lees second. It's Mark Twain's distinction between the right word and the almost-right word – between lightning and the lightning-bug. Lees's concerto premièred in 1968 with Graffman as soloist and Leinsdorf conducting the Boston Symphony Orchestra. Thirty-three years later, this may be its first commercial recording.

Lees has always been a musical dramatist, even in abstract works. The concerto form suits him, and he's written several, including concertos for each of the principal sections of the orchestra – string quartet, brass choir, wind quintet, and percussion. Here, he opposes sharply-contrasting ideas, each distinctive in itself. The first movement, a lickety-split toccata, exploits what Lees calls a "trill" idea and what I think of as more of a skip. The skip gets extended into rat-a-tat runs, which Lees contrasts with slower, punchier versions of themselves and the initial skip. The skip is never absent for long, even in a lyrical theme, where it becomes a kind of grace note. As the work continues, one becomes more and more aware of links among what one originally thought of as separate ideas. Eventually, they become different aspects of the same idea. The movement runs to probably some version of sonata form, but the listener is more aware of an idée fixe in constant transformation and running into itself. Even more important, Lees shows his mastery of symphonic rhetoric. He seems to create a movement of constant excitement because he knows just when to hold back and when to apply the gas again. It will leave you breathless.

The second movement opens with a real trill idea and elaborates it yet another way. Lees tells an emotional "story" of a struggle against stasis. So many of the themes emphasize one note and snap out of it only at the impulse of a trill. Even the timpani seems to trill. Like much of Lees's music, there's not a hummable tune, but the composer presents his ideas so clearly and so powerfully, that you don't miss the opportunity to whistle along. Lees interrupts his slow movement with yet another quick toccata passage of trills, which leads to a remarkable section where the trill slows down to its motific atoms: the rising and falling half-step. Lees tells us about that for a bit and then ends the movement with a dialogue between the piano and timpani recapitulating material from the movement's opening.

The rondo finale, a sort of Mr. Toad's Wild Ride, comes up with a theme filled with half-steps, which, as we have heard, the composer has connected to the skip idea. Most of the episodes (excepting a very Stravinskian idea of an upward-thrusting minor third) seem related to the main theme. Like all of Lees's music, the concerto is architecturally tight, even rigorous, but this all serves the emotional drama. Most listeners would, I believe, hardly notice, but I think most would thrill to its power. Lees music, above all, connects, not only to itself but directly to the listener. This is music for the body, as well as the brain. If you can keep still, you're probably dead.

Ian Hobson does a marvelous job. He takes on the role of concerto-hero heroically. He is in your face. His fingers not only find the right notes, they rage and brood with them. Hobson has also made a terrific recording of some of Lees's solo piano music, including the fourth sonata (Albany TROY227).

Copyright © 2002, Steve Schwartz