The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

-

Bach Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

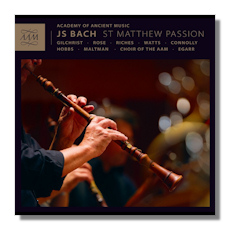

Johann Sebastian Bach

St. Matthew Passion

- Elizabeth Watts, soprano

- Sarah Connolly, mezzo Soprano

- James Gilchrist, tenor

- Thomas Hobbs, tenor

- Christopher Maltman, baritone

- Ashley Riches, bass

- Matthew Rose, bass

Richard Egarr, harpsichord

Choir of the Academy of Ancient Music

Academy of Ancient Music/Richard Egarr

AAM Records AAM004 2:24:38

This lovely performance of Bach's Matthew Passion was recorded at Saint Jude-on-the-Hill, London in April 2014 with Richard Egarr conducting from the harpsichord. Even he prefaces his essay on the work and recording by mentioning the fact that at Easter time "literally hundreds of performances of this work are (un)necessarily churned out to meet the eager demands of folk who seem to view the piece as actually "being� Easter." This is startlingly honest: there are 90 recordings in the current catalog.

Nor would it have been sufficient to embark on yet another merely because a member of the AAM Society wanted to support such en enterprise as a gift to his children, which is how it actually did come about. Only marginally more justifiable is the fact that the venerable Academy of Ancient Music has not previously recorded the work in its 40-year history. And that's a history that's seen 300 CDs. Egarr does, though, have a production of the Passion at Glyndebourne to his credit. Two aspects contribute to the recording's potential for "landmark" status: that Egarr and his forces have something new, fresh and enduring to say; and that an already superlative cast of singers – including James Gilchrist, Sarah Connolly, Thomas Hobbs, Elizabeth Watts, Christopher Maltman, and Matthew Rose – is on very top form.

You hear distinction, projection, strength of vocal personality and a compelling depth of interpretative confidence from the start; from each of these soloists: Watts' singing is close, very "real", human, fallible (and not only because she's so closely-miked, in common with the other soloists), for instance. Both James Gilchrist (Evangelist) and Matthew Rose (Jesus) sing with a splendid balance between warmth and authority. The choir is full, effecting and at times even mordent. Certainly always decisive and clean.

As the Passion progresses, the singers draw the listener into the drama. Their plan is not to "pile" events, tensions, impending death, onto the music. Nor to let the music's course simply "flow". Each moment seems to be the only one that matters – each juncture, dialog, reflection, regret, even each hope. Egarr makes the cumulative effect of concentrating on the text as purveyor of suffering responsible for the impact which the whole work ultimately has on us – rather than explicitly emphasizing the work's arches, structure and trajectory. At no time is the interpretation spuriously colored with romantic or tragic overtones. Listen, for example, to the crisp, trenchant pace of "So ist mein Jesus nun gefangen" [CD.1 tr.35]: Egarr sees no need to play up the possessive adjective; the tone of the soloists and the bite of the interjecting chorus convey the extent to which this must be a personal loss. That's surely what Bach wanted his congregation to… celebrate.

The tone of the performance is every bit as serious and full of weight, dignity, sobriety even, as needs to be the case in order for Bach's intentions to emerge. At times one feels that the composer was pulling wayward (church) authorities up short, back to order, by the monumental nature of his creation. Perhaps even worshippers, for whom attendance may have become somewhat routine, needed something different! It's not easy to convey the immensity of such a work as this Passion without at the same time betraying – and so inevitably diluting – the emotional impact (these days, on the listener) through pompous delivery, lugubrious playing and self-importance in tempi and phrasing.

Yet this balance between energy and depth is precisely what Egarr has achieved. Using the 1727 version, rather than those at which Bach continued to work after the first performance. Egarr manages to bring out the multiple layers, allusions, references beyond the purely narrative which abound in the libretto by "Picander" (Leipzig poet Christian Friedrich Henrici). To the fore here are the chorale tradition, Luther, meditative practices, an emerging sense of the (validity of portraying dramatically the) individual's capacity for suffering, the emerging Baroque opera aria.

Some of the best St Matthew Passions on record have been the result of a few – or even single – sessions. This one, though, was recorded over five days. Yet none of the impact that should come from what was conceived as a single, stupendous occasion in the Thomaskirche, Leipzig, at the service of Vespers on Good Friday, 11 April 1727 has been lost. If anything, the relaxed yet rigorous approach taken by Egarr and his forces is quietly cumulative. It has the particular merit of letting the text convey the emotion, liturgical import and ultimately the musical result.

One is reminded of the religious painting of the time (especially Depositions) which simultaneously invites us to empathize with the specific horror of the Biblical story examined here; yet extracts a more enduring message of hope, the reason for which believers believe Christ died. Egarr mirrors the dichotomy between an almost static, focused scene, about which the artist appears to be making no, or minimal, comment; and the inevitable plangency and range of emotional response which attending humans must make to the Passion. So his singers are encouraged to push expressiveness ever outwards; and at the same time make a virtue of restraint. The results are polish, communicativeness, involvement; admiration, even. This is made all the starker by yet another positive feature of these singers: effortlessness. And an effortlessness that comes from conviction, not casualness. Again, this is fully in keeping with the way in which reflection is privileged over drama here. At the same time, there is nothing slick or sleek about this performance; substance is everything.

The acoustic is close, responsive and wholly appropriate to the scale and dimension aimed for in this performance and recording. Yet it is not a "noisy" one. A is 415; and the instruments are period ones, of course. There is as much polish as there is any incidental sense of music-making. This aids the gravitas which distinguishes this performance. The two CDs come in a hardback 5" or so square booklet. As well as introductory material by Stephen Rose, the full text in German and English, there are color photographs from the recording sessions, singer biographies and photographs and full listings of the 33 orchestral players and 20-strong two choirs. There is much to recommend this recording. Technically adept, quietly eloquent, imaginative in conception, it in many ways epitomizes what a performance from the middle of the second decade of the present century sounds like when it takes into account the relevant scholarship, the entirely justified skills and strengths of specialist singers in particular; and the understanding that – for all the Matthew Passion originated as music for a single occasion – it is (also) music for all time.

Copyright © 2015, Mark Sealey