The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

Recommended Links

Site News

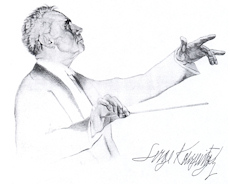

Serge Koussevitzky

Concert Programs, Paris 1921-28

Introduction

In 1924 Serge Koussevitzky, at the age of 50, assumed the conductorship of the already renowned Boston Symphony Orchestra and would lead it brilliantly until 1949. As Boston music critic (and later director of Columbia Masterworks of the Columbia Recording Corporation) Moses Smith writes in Koussevitzky (1947), as early as "the middle of the 1929-30 season Olin Downes of the New York Times had called Koussevitzky's Boston Symphony 'an orchestra which is without a superior if it has an equal in this country, a band that Mr. Koussevitzky has brought to unique flexibility, sensitiveness and virtuosity.'"[i] In 1967 The New York Times' music critic, Harold C. Schonberg, wrote in his superb The Great Conductors: "Many thought that under his [Koussevitzky's] baton the Boston Symphony Orchestra was the greatest in the world, superior even to so virtuoso group as the Philadelphia Orchestra under Stokowski."[ii] Calling Koussevitzky "The most important of all Russian conductors,"[iii] Schonberg noted: "In his day Koussevitzky was one of the big three of American conductors, the others being Toscanini and Stokowski."[iv]

In his early career, Koussevitzky (born c. 1874 in Vishny-Volotchok, Russia; died 1951) had established himself as not only the world's greatest living double-bass player,[v] but also as "the leading conductor in Russia… even though he was opposed to the [Boshevik] regime"[vi] – a regime that confiscated a significant part of the huge fortune that he had acquired through marrying his second wife, Natalya Konstantinova Ushkov, who would be his cultured life-long companion, devoted supporter, and adviser.

In Russia – well before his Boston Symphony tenure – Koussevitzky had become, as composer and musicologist Hugo Leichtentritt observes, "a champion of international modernism in music,"[vii] just as he would continue to be during his years in Boston. "The new works of Debussy, Ravel, Richard Strauss, Mahler, Reger, Sibelius, Busoni, and many others were introduced by him to Moscow's public, and in exchange he performed important new Russian works in his concerts in other countries…. Although he was appointed chief conductor of the Russian State Orchestra (the former Imperial Orchestra) in Petrograd by the provisional government after the first revolution, he found it expedient to leave Russia altogether in 1920 when the Bolshevik government was established."[viii] Between his dazzling career in Russia and before his 1924 arrival in Boston, Koussevitzky visited Berlin and then spent four important (and still not sufficiently explored) years in Paris from 1920-24; there he formed an orchestra and, as its conductor, "soon injected new blood into the then somewhat anemic body of Parisian music… and had influence far beyond the French capital."[ix] In 1921 he created a series of concerts which he called Grands Concerts Symphoniques Koussevitzky; after April 20, 1922, these concerts "were given semi-annually, one series in the spring, one in the fall."[x] (Even after Koussevitzky went to Boston, he would annually return to Paris and until 1929 conduct concerts).[xi] As Smith states, the Grands Concerts Symphoniques Koussevitzky "became an important artistic expression of postwar Paris. Their vogue was something like that of Diaghilev's Ballet Russe earlier. The audiences were the finest and the smartest in Paris. Nobody who was anybody or wanted to be anybody in music could afford to ignore the Koussevitzky concerts. They were the very latest fashion, le dernier cri. Koussevitzky, still his own manager, as during most of his Russian days, had the best musicians in Paris for his concerts, and he could rehearse them adequately. He was now a conductor of singular magnetism, eloquence, and persuasiveness. He had style, not only musical style but also – what must have counted even more heavily for the Parisians – personal style, dignified, and graceful deportment…. Koussevitzky was now the grand seigneur among musicians in Paris, as he had been years before in Berlin and after that in Moscow."[xii] In 1924 Olin Downs referred to him as "the conductor of the hour in Paris."[xiii]

While based in Paris, Koussevitzky also guest conducted widely, in, for example, such major European cities as Warsaw, Rome, Lisbon, Barcelona, and Madrid; he led the Berlin Philharmonic and performed with the best orchestras in England, including the London Symphony Orchestra. In fact, according to Smith, "Koussevitzky's concerts in London during his last full year in Europe contributed almost as much to his reputation here [in America] as the longer Parisian series."[xiv]

Although not normally remembered as an opera conductor, in 1922 Koussevitzky successfully performed Moussorgsky's Boris Godunov and Khovanstchina at the Paris Opera. "His principal operatic experiences, however, were on the Iberian peninsula"[xv] from 1922-24, where he not only conducted symphonic concerts with local ensembles, but also "presented a considerable operatic repertoire…. Among the operas presented were Boris Godunov, [Borodin's] Prince Igor, and [Tchaikovsky's] The Queen of Spades…. The operatic performances particularly had much success."[xvi]

Just as Koussevitzky championed new music while still conducting in Russia and continued to do so in Boston, in Paris his programs likewise represented a fascinating mixture of the more standard repertoire coupled with numerous new works by then (and sometimes still now) little-known or little-appreciated composers. Many of them are significant names today. As the critic for Le Ménestrel wrote in 1924: "… modern musicians, both French and foreign, owe much to M. Koussevitzky."[xvii] And, as Schonberg has noted, "the Concerts Koussevitzky… introduced, among other things, Ravel's orchestration of the Mussorgsky [sic] Pictures at an Exhibition, Honegger's Pacific 231 and music by Prokofieff and Stravinsky,"[xviii] adding, "Quite evident was the Franco-Russian imprint that was to persist for the next quarter of a century."[xix]

As musically rich and historically important as Koussevitzky's Paris period was, we now present here photocopies of many of the original programs from Koussevitzky's Paris concerts, as well as published lists, by year, of the musicians in his orchestra – distinguished players such as the harpist Lily Laskine, whose career extended well into the 20th century and who also performed as a soloist in Koussevitzky's Paris orchestra. Interestingly, "The [Boston Symphony] orchestra which faced him at the beginning of his second season contained many strange faces. In a few cases the changes were not replacements, for the string section was slightly enlarged. Otherwise, almost a score of old members were discharged in favor of Koussevitzky's appointments, foreign musicians. Some of the newcomers were old Russian friends; most of the others were Paris musicians who had served at the Concerts Koussevitzky."[xx]

To the best of my knowledge this article represents the first published compilation of Koussevitzky's Paris concert programs and their lists of musicians. The reprinted material which follows was made available during my research in the music department of Paris' Bibliothèque Nationale and is reproduced with their most generous permission. As for the programs themselves – whose visual design should itself be of wide historical and artistic interest – they can provide readers with the opportunity to see not only the intriguing range of composers and their works which Koussevitzky performed, but also to study the degree to which he sensitively arranged the sequence of his chosen pieces – famous and less so, modern and old – for a given performance. Regarding little-known composers, how many readers, for example, will recognize such individuals as the following: Filip Lazar, Ernest Toch, Alexandre Tansman, Germaine Tailleferre (the sole female member of the avant-garde composers' group called "Les Six"), Lili Boulanger (Nadia Boulanger's highly talented younger sister), Maurice Délage, Nicholas Obouhow, Henry Eichheim, Borchard, Polaci, Kastalsky, and others? But as for famous soloists, how pleasantly evocative a trip down music's memory lane it should be to encounter, though perusing Koussevitzky's programs, such landmark names as Alfred Cortot, Jacques Thibaud, Serge Prokofiew [sic], Robert Casadesus, Wanda Landowska, and Igor Strawinsky [sic] (as pianist in an all-Stravinsky, May 21, 1924 program). May the material that follows be of interest and value to all lovers of fine music and its history.

Browse by Year

ALL – 1921 – 1922 – 1923 – 1924 – 1925 – 1926 – 1927 – 1928

Links to All Programs

Salle Gaveau - April 22 & 29 and May 6, 1921

Théâtre National de l'Opéra - November 24, 1921

Théâtre National de l'Opéra - December 8, 1921

Théâtre National de l'Opéra - April 20 & 27 and May 4 & 11, 1922

Théâtre National de l'Opéra - May 11, 1922

Théâtre National de l'Opéra - 1922 Cover

Théâtre National de l'Opéra - 1922, 3rd Season Last Page

Palais du Trocadéro - March 4, 1922

Théâtre National de l'Opéra - May 4, 1922

Théâtre National de l'Opéra - October 26, 1922

Théâtre National de l'Opéra - October 12, 19, 26 and November 9, 1922

Théâtre National de l'Opéra - November 9, 1922

Théâtre National de l'Opéra - May 1923

Théâtre National de l'Opéra - May 10, 1923

Théâtre National de l'Opéra - October 11, 1923

Théâtre National de l'Opéra - October 18, 1923

Théâtre National de l'Opéra - November 8, 1923

Théâtre National de l'Opéra - May 21, 1924

Théâtre National de l'Opéra - May 23, 1925

Théâtre National de l'Opéra - May 30 & June 6, 1925

Théâtre National de l'Opéra - June 6 & 13, 1925

Théâtre National de l'Opéra - May 27, 1926

Théâtre National de l'Opéra - June 3, 1926

Théâtre National de l'Opéra - June 3, 1926

Théâtre National de l'Opéra - June 12, 1926

Théatre Des Champs-Élysées - 7th Season 1927

Théatre Des Champs-Élysées - May 21, 1927

Théatre Des Champs-Élysées - May 28, 1927

Théatre Des Champs-Élysées - June 4, 1927

Salle Pleyel - May 24, 1928

Musician Lists

Théâtre National de l'Opéra - 1922 Season

Théâtre National de l'Opéra - 1923 Season

Théâtre National de l'Opéra - 1923 Season, 4th Concert

Théâtre National de l'Opéra - 1925 Season

Théâtre National de l'Opéra - 1926 Season

Théâtre National de l'Opéra - 1927 Season

Victor Koshkin-Youritzin

Vice President, Koussevitzky Recordings Society, Inc.

David Ross Boyd Professor, History of Art

The University of Oklahoma

Norman, OK 73019

Published December 3, 2010

END NOTES

Please note that the typed text that follows each program exactly reproduces the original program and does not correct any possible errors. Readers will, at times, be able to see some inconsistencies in spelling and punctuation from one program to another.

[i] Moses Smith, Koussevitzky, Allen, Towne & Heath, Inc., New York, 1947, p. 215.

[ii] Harold C. Schonberg, The Great Conductors, A Fireside Book published by Simon and Schuster, New York, 1967, p. 303.

[iii] Ibid., p. 302.

[iv] Ibid., p. 307. Comparing this trio, Schonberg continues: "Of the three, Koussevitzky was by far the most important to the cause of American music, for in him the composer had a spokesman and an exponent. In addition, Koussevitzky's taste was catholic enough to include the most significant works of the modern European school, with the exception of twelve-tone music."

[v] Regarding earlier, eminent performers, Smith on page 15 states: "Only two double-bass players had careers that might be described as notable. Domenico Dragonetti was a celebrated virtuoso on the double-bass at the end of the eighteenth century and the first part of the nineteenth…. Half a century later another Italian, Giovanni Bottesini… achieved on it [the double-bass] a phenomenal proficiency, which was celebrated in musical capitals all over Europe. Since he died as late as 1889 his fame was still relatively fresh when Koussevitzky began his double-bass career."

[vi] Smith, p. 102. As highly regarded as Koussevitzky was in Russia, Rachmaninoff – his competitor as a conductor in Russia – was offered the Boston Symphony orchestra twice before it was offered to Koussevitzky, in 1909/10 and 1918. As Harold Schonberg states in his book, The Great Conductors (pp. 301-302), "It is not generally known that Rachmaninoff would have become as great a conductor as he was a pianist…. After leaving Russia for good in 1917, Rachmaninoff was offered several American orchestras, including the Boston Symphony, but decided to stick to composition and his piano. He conducted no public concerts thereafter. But around 1940 he led the Philadelphia Orchestra [his favorite orchestra] in a recording of his Third Symphony, and it is a remarkable performance – sharp, with superbly articulated rhythms characteristic of his work at the piano, full of authority, strength and aristocracy. The world lost a major conductor when Rachmaninoff turned elsewhere." It can be added that two other recordings testify to Rachmaninoff's extraordinary power as a conductor: performances with the Philadelphia Orchestra of his Vocalise and particularly of his tone poem (based on one of Arnold Böcklin's paintings of the same title), The Isle of the Dead. The latter is, in my opinion, one of the most amazing and profound of all orchestral recordings – almost superhuman in its power, evocativeness, and orchestral playing (the musicians perform as if they were literally bewitched) – and finer, more moving, and more tightly structured than even Koussevitzky's splendid recording of the same piece. For readers interested in hearing these Rachmaninoff performances – as well as, for example his unparalleled performance of his Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini with Stokowski and the Philadelphia Orchestra (one of the greatest ever recorded collaborations between soloist, conductor, and orchestra) – I urgently recommend that readers listen to the pieces on LP rather than the (to my ear) generally inferior CDs, which, especially in the case of the Rhapsody, do not at all capture the performances' richness, depth, and gripping interpretative power. In too many cases, as many connoisseurs are aware, LPs are superior to the CDs – another important and regrettable example of this phenomenon being Wilhelm Furtwängler's glorious July 29, 1951 performance with the Bayreuth Festival Orchestra of the Beethoven Ninth Symphony.

[vii] Hugo Leichtentritt, Serge Koussevitzky: The Boston Symphony Orchestra and the New American Music, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Mass., 1947, p. 8.

[viii] Ibid., pp. 8-9.

[ix] Ibid., p. 9.

[x] Smith, p. 111.

[xi] José Bowen, "Koussevitzky," The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, 2nd Edition, Vol. 13, Stanley Sadie, ed., MacMillan Publishers, Ltd., London, 2001, p. 845.

[xii] Smith, p. 111.

[xiii] Ibid., p. 121. (See also p. 359, note 5 under chapter IX.)

[xiv] Ibid., p. 122. Smith states, "The reason lay in the reviews and critical comment. The English writers were often more articulate than the French, and they were more objective. In addition, their articles were immediately available for reprint in America without the intervention of the translator."

[xv] Ibid.

[xvi] Ibid., pp. 113-114.

[xvii] Ibid., p. 117. (See also p. 359, note 4 under Chapter IX.)

[xviii] Schonberg, pp. 305-306.

[xix] Ibid., p. 306.

[xx] Smith, p. 175. Regarding the exact number of replacements, it may be pertinent to cite H. Earle Johnson, who states in his Symphony Hall, Boston (Little, Brown and Company, Boston, 1950, page 101): "At the conclusion of his [Koussevitzky's] second season twenty-two replacements were made, about half through discharge of musicians no longer in his [Koussevitzky's] judgment equal to the tasks before them; the remainder were through resignation. …[T]he principal was re-established that a conductor is entitled to control the personnel of the orchestra, since he is to be held accountable for its performance."

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I am most grateful to a number of individuals for their especially kind and valuable assistance – direct or indirect – in my preparation of this article. The University of Oklahoma's Research Council awarded me travel funds in connection with this project. Mme. Catherine Massip, then-director of the Music Department of the Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris, and her outstanding staff were extraordinarily gracious and helpful in making the Bibliothèque's extensive information about Koussevitzky's Paris years available to me. I deeply appreciate Mme. Massip's having given me permission to reproduce this material. In Paris, the internationally acclaimed writer and de Beauvoir scholar, Dr. Claudine Monteil-Serre, provided much-needed hospitality and encouragement. Another longtime, dear French friend of mine, Mme. Agnès de Tristan (we met during our college days, when she was at Smith and I at Williams), very kindly let me stay with her and her wonderful family at their beautiful Paris home, during my period of research. Susan Grossman and her lovely family were also most hospitable to me in Paris. Sharon Burchett – a former art history instructor at the University of Oklahoma and currently Assistant to the Director of OU's Charles M. Russell Center for the Study of the Art of the American West – and Kevin Burchett very generously and expertly scanned Koussevitzky concert programs and other material reprinted here. Tom Godell – an internationally esteemed music critic and both founder and President of the Koussevitzky Recordings Society, Inc. – has, for many years, encouraged and supported this project. Dave Lampson – founder of Classical Net – has my warmest, most heartfelt gratitude for collecting all my material and so effectively editing, formatting, and publishing it. He even painstakingly typed out all the programs to ensure ease and accuracy of reading. Without his invaluable advice and support, this publication would not have been possible.

Three other individuals merit very special acknowledgement. First is my friend of over 50 years, the distinguished New York-based opera conductor (and Leopold Stokowski's former Associate Conductor), Anthony Morss, who knew Koussevitzky personally, is an authority on him and his career, and spent countless hours discussing him with me over the past decades. Maestro Morss provided me with his ever-astute advice with this article. Over the years I have published extensive interviews with him in the Koussevitzky Recordings Society Journal (concerning our interview regarding Koussevitzky, please see the Spring 1995 issue; about Stokowski, please refer to the four-part interview carried in the following KRS journal issues: Fall 1996, Spring 1997, Fall 1997, and Spring 1998). My beloved late Mother, Tatiana Koshkin-Youritzin – a superb classical pianist, protégée of Michel Fokine, and (before she turned full-time to motherhood) a principal member of the corps de ballet of New York City's Radio City Music Hall – introduced me, as a child, to the magic of Koussevitzky's artistry. And, finally, my fidèle compagnon de l'esprit for more than a quarter of a century, Cynthia Lee Kerfoot – scholar, writer, and music critic of impeccable judgment – has my deepest thanks for her perceptive editorial and technical advice, and for her constant, loving support.