The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

Recommended Links

Site News

Koussevitzky Recordings Society

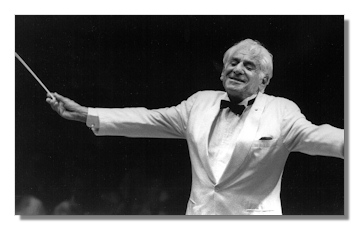

Leonard Bernstein on Koussevitzky

From the 1974 Koussevitzky Symposium at Tanglewood

Short excerpt from the article appearing in the Koussevitzky Recordings Society newsletter

The Koussevitzky dream, the much spoken of dream which is symbolized and represented in a most tangible way by this glorious place, is not fully realized by any means. It is in the nature of a vital vision that it not ever be realized. Complacency is death. When that sets in, the Sergei Alexaunch's vision will have died. The way it can be kept alive, the only way, is to keep developing it, keep seeing it through.

For example, one of his original ideas was to have a Berkshire Music Center Orchestra, a student orchestra which was truly international, not just American. That was one of the first things I ever heard him say. This was not possible in that great decade between 1940 and 1950 when he was reigning here, because of a certain war and because of certain post-war conditions which made travel difficult and international relations a bit strained. This week I found myself conducting a student orchestra called the World Youth Orchestra, and we gave a concert yesterday afternoon in celebration of his birthday. This ought to be the Berkshire Music Center Orchestra; this is suddenly, by happenstance, one of those fulfillments of his original vision. It wasn't easy to do, but there were representatives of twenty-five different countries in the orchestra. Now there's something to work for. It's difficult; it's expensive; it's complicated; its administratively very demanding – but it can be done. That's something I would like to see happen here, because he would have liked to have seen it happen.

Tanglewood was not to be parochial, provincial, ever, even if the province was as large as the United States of America. It had to be international. That was the big aura that surrounded this dream. He was very nationalistic in other ways: he was very Russian. As Aaron has beautifully put it, he was very nationalistic about the growth and development of American Music. He became almost more American that we Americans in his passion for seeing American music develop. But it spite of all these various nationalisms, he was a universal man if I ever met one. And there was no part of the world that he did not want to see incorporated somehow or other into this dream which is Tanglewood.

He also said that at this place there would come the great thinkers of the world to stimulate and provoke the young and to disseminate new ideas. We have marvelous thinkers here, but they're all musicians mainly. Something else I think that Tanglewood still has to do is to bring in thinkers who are related to the arts but not necessarily artists – philosophers and writers, particularly poets, who can flesh out the purely musical activities of Tanglewood. I'm perfectly aware, having been a student here since it was first founded, that it takes all the time you have and then some to get the musical work done. In those days, I don't think we ever slept an hour. We worked twenty-four hours a day and loved it. But there is always time for that extra injection of a non-musical idea, of what is apparently a non-musical idea which immediately ties up in an interdisciplinary way. That was a very essential part of his vision, and it has not yet quite happened.

Another thing I would like to see happen here is the resurrection of the opera department. That was so close to his heart, and perhaps one of his proudest days – or nights – was in this building when he stood and made a little speech before the American premiere of Benjamin Britten's opera Peter Grimes, which had been commissioned through his Foundation. He spoke very glowingly of the opera, but the real pride was that he was able to bring together in this building singers, conductors, scenery, lighting – everything that goes into making an opera. Another aspect of his universality was the bringing together of the arts. He had very grandiose plans about this. I remember every year he would discuss with me the possibility of what he called a "pagan". It took me a long time to know what he meant by a "pagan". I had visions of bacchanalian rites and people going mad with tortures and drunk with wines. What he meant was a pageant. He had it all figured out in that decline there near the west barn. There is a natural amphitheater. Every once in a while we'd go down there and test it out acoustically. I would sing something, and he would stand at the other end and listen; he would sing something and I'd stand there. He said, "This is perfect for our pagan"; and he would assign to me the task of making a pagan. I'm not so keen on pagans myself. They can turn out to be very corny and overblown, but one of these days we're going to have a pagan, and we're going to have it every year, once we get the hang of how to do it in an unpretentious way. What he meant by a pageant, of course, was something again that would bring together the arts, and even the sciences, and would bring together great minds that could collaborate and feed one another. Out of this would come something quite new.

I hate to talk about Koussevitzky in personal terms because it always winds up being jokes and making fun of his accent. I've only one reminiscence which popped into my mind when Seiji was talking about his first interview with me in Berlin. I suddenly remembered my first interview with Koussevitzky. I'd never met him, although I'd grown up in Boston with him as the great conductor – this remote figure that I would see from way up in the second balcony. I never expected to meet him; I'd never thought of being a conductor. That hadn't occurred to me until long after I graduated from school. He was just somebody I worshipped. After I did graduate from school, I went to the Curtis Institute for a season and studied with Fritz Reiner – that was 1940. I read in the paper somewhere that Serge Koussevitzky was opening a school to be known as the Berkshire Music Center, and I decided, of course, that I had to go. So I rounded up all the letters of recommendation I could – one was from Fritz Reiner, one was from Aaron, bless him, Roy Harris, the various musicians I had met of prowess and dignity and importance.

Armed with this sheaf of letters, I arrived at Symphony Hall and was brought into the Green Room shaking. I can't tell you what a way I was shaking. The Green Room is very impressive. It's full of statuary, had a bust of Sibelius, and, of course, a bust of Koussevitzky. It was gloriously furnished, and it seemed to me the most palatial place in the world. Very different from the Green Room at the Shed here, which is a kind of backwoods outhouse. With knees trembling, I was ushered into the presence of a great man. I presented these letters, which he didn't even read; and he said, "Please sit down." Richard spoke of the charisma; he spoke of the grand seigneurism, of the way he made you feel at ease. This is all perfectly true. I suddenly found myself sitting down and feeling rather comfortable. He asked me about myself. He asked me about Fritz Reiner, of course, slightly mischievously – as one conductor does ask about another. "How do you find your experience with Reiner? He's a good man – yes…good man." We talked about one thing and another, and suddenly he said, "But of course I vill take you in my class." I thought, "This is incredible. I mean, isn't he going to ask me to beat three or play the piano or do something to audition?" Nothing. And he hadn't even read those letters. I suddenly realized that there was an innate genetic connection from that moment when he said, "Please sit down", and I sat down. It was a love affair. It was a father-and-son relationship if you like, a surrogate father, but it was more than that. I can't even name it. There was something we had in common that I call innate. We share some genes; I don't know where they come from, but we had them in common, from that moment until the moment he died.

I think I was the last one to talk to him. The night before he died I held him in my arms in the hospital, and we talked for three hours. The last thing I remember him saying to me was "Keep the Tanglewood dream growing." 'Growing' is the key word. Tanglewood is here; the dream is palpable. But it must keep growing; otherwise it will stagnate. And I come back to the word 'complacency'. Let's for God's sake, avoid it.