The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

-

Find CDs & Downloads

Amazon - UK - Germany - Canada - France - Japan

ArkivMusic - CD Universe

Find DVDs & Blu-ray

Amazon - UK - Germany - Canada - France - Japan

ArkivMusic-Video Universe

Find Scores & Sheet Music

Sheet Music Plus -

Recommended Links

Site News

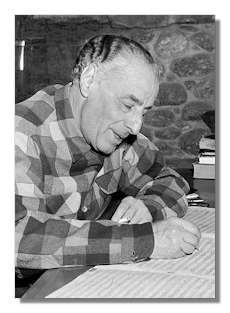

Ernst Toch

(1887 - 1964)

The life of Ernst Toch (December 7, 1887 - October 1, 1964) began almost like a composer's Hollywood biography. Born in Vienna to a lower-middle-class Jewish family, he was not permitted to study music, due to the concern of his parents that first, it wasn't quite respectable and second, it was a hard way to make a living. They insisted he study medicine, which he did. Yet Toch so burned to compose that he secretly taught himself to read music and began to write. He came across a collection of "famous" quartets by Mozart and decided to learn something just by copying them out. He quickly became bored with that and devised a game in which he would take a paragraph of Mozart and continue with his own paragraph, then go back to Mozart and compare. He was so humbled by the result that he thought hard about the differences and kept this up through every measure of every quartet in the volume, in effect taking lessons from Mozart. He did all of this in secret. One writer has called this one of the most amazing courses of self-instruction ever undertaken. At 18, somehow overcoming his parents' objections, Toch not only entered the Vienna Conservatory as a part-time student, but a string quartet he had written received a performance from the prestigious Rosé Quartet in the Musikverein. This overcame parental resistance, and he could now turn his full attention to music. In 1909, he received Vienna's Mozart Prize and moved to Frankfurt to study with Iwan Knorr, the teacher of Ernest Bloch, Cyrill Scott, Percy Grainger, and Hans Pfitzner, among others. During World War I, he served in the Austrian army.

Toch's music before the war owed a lot to Brahms. After the war, with his String Quartet #9 (1919), he got caught up in various currents of the German avant-garde: Expressionism, Neue Sächlichkeit, Zeitoper, Gebrauchsmusik, and so on. The Twenties to the rise of Hitler saw his biggest successes. He became a fixture at the major European festivals of contemporary music. Critics mentioned him in the same breath as Schoenberg, Hindemith, and Weill.

When the Nazis came to power, Toch left. Actually, he had been attending a music festival in Italy as an official German representative, along with Richard Strauss, when he got the news. He sent his wife a pre-arranged telegram: "I have my pencil." She packed up and met him in Paris. The Tochs did not stay long. German refugees in Paris had a hard time finding work. They moved on to London, but Toch ran into the same problem. Nevertheless, he began to pick up jobs scoring for movies, mainly those of Korda. In 1935, he received an appointment at New York City's New School of Social Research, which brought over many German and Jewish refugees – indeed, the cream of European intelligentsia, including Erwin Piscator, Hannah Arendt, Leo Strauss, Roman Jakobsen, Jacques Maritain, and Claude Levi-Strauss. In 1936, he began to get commissions for film scores by the Hollywood studios, and he made his final move to southern California. He earned three Oscar nominations.

However, he could not interest anybody in his concert work, the music that mattered to him. Furthermore, he grew depressed over events in Europe and learned that the Nazis had wiped out the family left behind. He found it very difficult to compose and, indeed, those works that he completed sound more dutiful than inspired. After the war, he began writing again, hoping to re-establish himself in Europe, but Europe's contemporary-music scene had passed him by. He settled into teaching at the University of Southern California and to composing major works, including a cycle of symphonies and more quartets and other chamber music. He won the Pulitzer in 1956 for his Symphony #3. He died in Los Angeles. As a teacher, he produced one of the classic textbooks of composition, The Shaping Forces of Music. It doesn't resemble any other composition textbook I know. Indeed, someone aptly described it as "a composer's vade-mecum." It prescribes no exercises. It doesn't talk about things like sonata. It concerns itself with the rhetoric of music, rather than its grammar or its architectural blueprint. It looks on musical form not as a static vessel to be filled, but as something that must be dynamically formed. It takes the view of a composer, initially faced with a blank page, who shapes an entire movement. It is filled with penetrating discussions of various masterpieces in the literature. You get the feeling you're in the garage, looking over the mechanic's shoulder as he works on your car with the hood up and talks out loud about what he's doing and why.

Toch's music undergoes several phases. His very early music owes a lot to Mozart, as you might expect. He then moves to a Brahmsian idiom. The Twenties show him experimenting in several different directions. Perhaps his most noted achievement during this time is his invention of the "spoken chorus," which notates dynamics, vocal registers, and precise rhythms, but no pitches. From this emerged undoubtedly his most popular work, the "Geographical Fugue" (Fuge aus der Geographie), which is indeed a real 4-part fugue illustrating several tricks of academic counterpoint, with a text consisting entirely of exotic (to an Austrian) place names. The final phase shows no sign of settling in. The Third Symphony, for example, calls for instruments of Toch's own invention (usually replaced by conventional instruments or, these days, by synthesizers). Each of his seven symphonies takes its own approach to form. Despite its chromaticism, Toch's music remains firmly tonal, sharing more with the music of the Weimar Republic (minus Schoenberg) than with that of postwar Europe. Although his catalogue includes genuinely humorous works, Toch's characteristic voice is grave. Curiously enough, the music still ennobles, a body of work that celebrates the humanistic mind. ~ Steve Schwartz

Recommended Recordings

Geographical Fugue

Geographical Fugue

Chamber Music

Chamber Music

- Piano Quintet, Op. 64; Violin Sonata #2, Op. 44; Burlesken, Op. 31; Impromptus, Op. 90c/Naxos American Classics 8.559324

-

Spectrum Concerts Berlin

- Piano Quintet, Op. 64; Piano Concerto #2, Op. 61/Classic Talent SACD DOM292970

-

Diane Andersen (piano), Danel Quartet; Hans Rotman/Halle State Philharmonic Orchestra

- String Quartets #6 & 7, Opp. 12 & 15/Classic Talent DOM291052

-

Braude Quartet

- String Quartets #8 & 9, Opp. 18 & 26/CPO 999686-2

-

Verdi Quartet

Orchestral Music

- Symphonies #1-7/CPO 777191-2

-

Alun Francis/Berlin Radio Symphony Orchestra

Amazon - UK - Germany - Canada - France - Japan - ArkivMusic - CD Universe - JPC

Or available separately -

Symphonies #1 & 4 on CPO 999774-2

Amazon - UK - Germany - Canada - France - Japan - CD Universe

Symphonies #2 & 3 on CPO 999705-2

Amazon - UK - Germany - Canada - France - Japan - CD Universe

Symphonies #5-7 on CPO 999389-2

Amazon - UK - Germany - Canada - France - Japan - Symphony #3, Op. 75 w/ Hindemith & Martin/EMI Matrix 72435-65868-2

-

William Steinberg/Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra

- Piano Concerto #1, Op. 38; Peter Pan, Op. 76; Pinocchio Overture; Big Ben, Op. 62/New World Records 80609-2

-

Todd Crow (piano), Leon Botstein/North German Radio Symphony Orchestra, Hamburg

- Piano Concerto #2, Op. 61; Piano Quintet, Op. 64/Classic Talent SACD DOM292970

-

Diane Andersen (piano), Hans Rotman/Hallé State Philharmonic Orchestra, Danel Quartet

- Cello Concerto, Op. 35; Tanz-Suite, Op. 30/Naxos American Classics 8.559282

-

Christian Poltéra (cello), Spectrum Concerts Berlin