The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

-

Find CDs & Downloads

Amazon - UK - Germany - Canada - France - Japan

ArkivMusic - CD Universe

Find DVDs & Blu-ray

Amazon - UK - Germany - Canada - France - Japan

ArkivMusic-Video Universe

Find Scores & Sheet Music

Sheet Music Plus -

Recommended Links

Site News

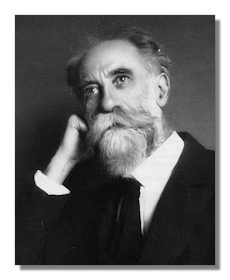

Charles Louis Eugène Koechlin

(1867 - 1950)

Born into a wealthy family of Alsatian textile magnates, Charles Louis Eugène Koechlin (November 27, 1867 - December 30, 1950) prepared to become an artillery officer but contracted tuberculosis which rendered him unfit for service. While recuperating in Algeria, the music bug hit him and pushed him into the Paris Conservatoire at the relatively late age of 23. He studied counterpoint with one of that institution's great teachers, André Gedalge (who also taught Maurice Ravel, among others) and composition with Jules Massenet and Gabriel Fauré. Fauré provided his compositional ideal.

Early on, Koechlin lived a comfortable life but ran into increasing financial burdens, which compelled him to spend a lot of time as a writer on music theory and as a private teacher. Indeed, during his life, he was probably better known as a theoretician. Furthermore, there was nothing he didn't know about technique. Debussy asked him to orchestrate his ballet Khamma (all but the prelude). He also provided the standard orchestrations for Fauré's Pellés et Mélisande and Emmanuel Chabrier's Bourrée fantasque. Poulenc went to him for lessons in orchestration and form.

Koechlin's music is so various, so eager to try different styles and to move to different inspirations (sometimes in the same piece) that one discerns a singular voice with difficulty. His muse sings as abundantly as Hector Berlioz's, but with a jaw-dropping variety. He excelled in every genre he tried – chamber music, song, ballet, and orchestral, with the exception of the symphony. His symphonies are either sui generis, rather than classical, or orchestrations of earlier pieces. His tone poems on Kipling's Jungle Book, particularly Les bandar-log, run a gamut of contemporary and just-past styles – Impressionism, neo-classicism, 12-tone serialism, and so on. Containing most of these styles, Les bandar-log may have begun in satirical intent, but the humor ultimately has no meanness in it. His Seven Stars Symphony (inspired by his favorites of the silver screen) delights in its unabashed fandom. The Chaplin finale in particular captures the wit of the comedian. Koechlin had a penchant for large-scale works, but his communist sympathies, especially during the Thirties (he never officially joined the Party), also prodded him to produce smaller-scaled and more directly communicative work like the 12 petites pièces très faciles and the 4 nouvelles sonatines, both for piano.

I supposed the oddest thing about Koechlin was his adoration of film stars, particularly a German-French actress, Lilian Harvey (born in England), almost completely forgotten today. He wrote several pieces to her and made his wife (!) write her several times to set up a meeting face to face. Later on, Ginger Rogers, who in her early film career resembled Harvey, also became a favorite.

Koechlin never received all that many performances while he lived, although the top composers in France greatly respected him. It is the modern recording that has allowed us to see why Fauré, Claude Debussy, Darius Milhaud, Albert Roussel, and Manuel de Falla made such a fuss. ~ Steve Schwartz

Recommended Recordings

Songs & Chamber Music

- Mélodies, Opp. 5, 22, 31, 35 & 68; Chansons pour Gladys, Op. 151; Poèmes d'automne, Op. 13; Poèmes d'Haraucourt, Op. 7; Rondels, Op. 1/Hyperion CDA66243

-

Claudette Leblanc (soprano), Boaz Sharon (piano)

- Piano Music I: Au loin, Op. 20 #2; Sonatinas, Op. 87; Paysages et marines, Op. 63; Premier album de Lilian, Op. 139; Second album de Lillian, Op. 149; /Hänssler 93.220

-

Michael Korstick (piano)

- Piano Music II: Les heures persanes, Op. 65/Hänssler 93.246

-

Michael Korstick (piano)

- Nocturnes, Op. 32bis; Suite en quatuor, Op. 55; Sonata for 2 Flutes, Op. 75; Divertissement, Op. 91; Sonatine modale, Op. 155a; Epitaphe de Jean Harlow, Op. 164; Trio, Op. 92; Pièce de flûte pour lecture à vue, Op. 218/Hänssler 93.157

-

Christina Singer (flute), Tatjana Ruhland (flute), Dirk Altmann (clarinet), Mila Georgieva (violin), Ingrid Philippi (viola), Joachim Bänsch (French horn), Libor Síma (alto saxophone & bassoon), Yaara Tal (piano)

- String Quartets #1 & 2, Opp. 51 & 57/Ar Ré-Sé 2006-3

-

Ardeo String Quartet

- Piano Quintet, Op. 80; String Quartet No. 3, Op. 72/Ar Ré-Sé 2009-1

-

Sarah Lavaud (piano), Antigone Quartet

Orchestral Music

- The Jungle Book: Poèmes du "Livre de la Jungle," Op. 18; La course de printemps, Op. 95; La méditation de Purun Bhagat, Op. 159; La loi de la jungle, Op. 175; Les bandar-log, Op. 176/RCA Victor Red Seal 09026-61955-2

-

Iris Vermillion (mezzo soprano), Johan Botha (tenor), Ralf Lukas (baritone), David Zinman/Berlin Radio Symphony Orchestra, Berlin Radio Chamber Choir

- Seven Stars' Symphony, Op. 132; Ballade for Piano & Orchestra, Op. 50/EMI L'Esprit Français CDM7643692

-

Bruno Rigutto (piano), Françoise Pellié (ondes martenot), Alexander Myrat/Monte Carlo Philharmonic Orchestra

- Le docteur Fabricius, Op. 202; Vers la voûte étoilée, Op. 129/Hänssler 93.106

-

Christine Simonin (ondes martenot); Heinz Holliger/Stuttgart Radio Symphony Orchestra

- Symphonic Piece "Au loin", Op. 20 #2; Sur les flots lointaines, Op. 130; Le buisson ardent, Opp. 171 & 203/Marco Polo 8.223704

-

Pascale Rousse-Lacordaire, ondes martenot), Leif Segerstam/Rheinland-Pfalz State Philharmonic Orchestra