The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

-

Introduction

Acoustics

Ballet

Biographies

Chamber Music

Composers & Composition

Conducting

Criticism & Commentary

Discographies & CD Guides

Fiction

History

Humor

Illustrations & Photos

Instrumental

Lieder

Music Appreciation

Music Education

Music Industry

Music and the Mind

Opera

Orchestration

Reference Works

Scores

Thematic Indices

Theory & Analysis

Vocal Technique

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

Book Review

Book Review

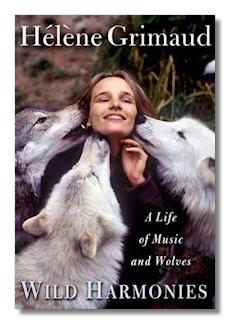

Wild Harmonies - A Life of Music and Wolves

Hélène Grimaud

Translation of Variations sauvages by Ellen Hinsey

New York: Riverhead Books [Penguin], 2006. 245 pages

ISBN 1594489270

Grimaud is rather young to be writing a memoir, unless she plans a series of them. And it is paradoxical for her to be so devoted to wolves, as the species is hierarchical in social its organization and she emphatically is not. But there are lone wolves on the periphery of wolf packs, and Grimaud can certainly be regarded as a kind of lone wolf herself.

There is a great deal of fact and myth about wolves in this book. Grimaud lived in voluntary poverty for years while saving her musical earnings to establish a Wolf Conservation Center, employing thirty people, in New York State, where she lives. It has had thousands of visitors, including autistic children.

Grimaud has always gone her own way. She presents herself, even as a young child, as "uncontrollable," "unmanageble," "unsatisfied." She confesses to "hurting" herself physically. Without siblings, she was friendless in school; a daydreamer, she interrupted to ask inappropriate questions, something she felt guilty about.

She did take to the piano at a very young age, made rapid progress, and impressed her music teachers. Following private instruction, she entered the Conservatoire at Aix en Provence at a very young age and spent four years there. At age eleven she played for the director of the Marseilles Conservatoire, Pierre Barbizet, who recommended that she prepare to enter the National Conservatoire in Paris. When she was barely thirteen she was admitted there, and did so well in the examinations that she was exempt from taking musical theory.

By in her second year in Paris Grimaud was already impatient with the course of study. She wanted to play complete concerti, not etudes. Risking expulsion, she went away without leave for a month. At Aix, before returning, she played Chopin's Second Concerto. She was now fourteen.

Back in Paris, her piano teacher not only agreed to listen to a tape of that concert but played it for the principal producer at Denon – who immediately decided to record her. He wanted Liszt. She insisted on Rachmaninoff. The CD was made in Amsterdam and Grimaud usefully describes how she coped with pre-performance nerves, then and later. Self-critical of the performance on that first commercial recording, Grimaud was fortunate in that it helped start her career.

By the time she was fifteen, she fulfilled the requirements for a premiere prix, which involved a juried competition and which admitted her to the third level of study, by the age of fifteen. After another two years she insisted in entering (against vehement advice) the Tchaikovsky competition in Moscow, easily persuading her sight- reading teacher, but not her piano teacher, to write the needed letter for her. She won no prizes. At seventeen, Grimaud decided to leave the Conservatoire.

She had decided to continue on her own. Her resolution was confirmed and encouraged by Leon Fleisher, two of whose master classes she attended, the second of which she found musically invaluable: "All at once, with just a few images, he made me understand the architecture of a piece and its importance, the directive force of the overall line." He told her "a pianist is an architect who uses rhythm as a basic building block" (p. 157). He advised her to begin slowly and perform as little as possible, but that she had what it takes to make a success of it. "Go to it," he said.

During the summer of 1987, she took the master class of the Cuban pianist Jorge Bolet at La Roque d'Antheron, where she had the choice of half a dozen grand pianos. They did not have a verbal language in common, but Bolet told an interviewer for Le Monde that Grimaud had a talent of "extraordinary quality and sensibility of temperament" (p. 166). Within hours Grimaud had an agent and a visit from the director of the festival. She also had been invited to play at the festival of Aix en Provence, the broadcast of which led Pierre Vozlinsky, the artistic director of the Orchestre de Paris, to invite Grimaud for an audition with Daniel Barenboim. Her Rachmaninoff 2nd Piano Concerto was released by Denon and won a Grand Prix du Disque. Denon asked her to make a second recording. Grimaud admits she was lucky.

She certainly seemed about to throw her luck away, though. Instead of working with Barenboim on a concert scheduled the day after a performance by Martha Argerich and Gidon Kremer (who were later to become friends) she insisted in hearing their performance instead of preparing for her own. Both Barenboim and her agent found her stubborn: she refused to play Saint-Saëns' second concerto which failed to please her; she refused to meet with a famous conductor whose conducting style she did not like. (A conductor she really did like working with later was Kurt Sanderling, with whom she recorded Brahms.) Nevertheless she began to tour in Germany, Switzerland, London, Japan and the United States. At the festival of Lockenhaus she began working with Argerich and Kremer and actually acting on their advice. From Kremer she learned to analyze scores better. She also learned to face her own errors and failures and the admission helped her to make progress. She gave up excessively fast tempos and abandoned the goal of perfection at any price.

After a period of illness and depression, Grimaud was invited to play in Cleveland. There she decided she wanted to return to the United States and not to return to France, evidently to shed a lot of baggage. "In the United States I was no longer out of step. No one found me strange" (p 195). She found energy and absence of snobbery; she got along better with people. She taught herself English in six months by listening to it in films and broadcasts. Her American tour ended in Florida, where she met a bassoon player named Jeff, with whom she established a relationship, and also a strange man with a pet wolf. That encounter changed her life. From a connection with this wolf she developed her interest in wolves in general.

I read this book, after hearing an interview with Grimaud on National Public Radio, out of curiosity and because I like some recordings of hers, in particular, the album called Credo (the featured work by Arvo Pärt); this includes her extremely fine performances of Beethoven's Choral Fantasy and Tempest Sonata (DG 471769-2). I also like her recording of the Ravel Concerto in G with Gershwin's concerto in F. The book is a strange and no doubt self-indulgent one but I found it fascinating.

Copyright © 2007 by R. James Tobin