The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

-

Introduction

Acoustics

Ballet

Biographies

Chamber Music

Composers & Composition

Conducting

Criticism & Commentary

Discographies & CD Guides

Fiction

History

Humor

Illustrations & Photos

Instrumental

Lieder

Music Appreciation

Music Education

Music Industry

Music and the Mind

Opera

Orchestration

Reference Works

Scores

Thematic Indices

Theory & Analysis

Vocal Technique

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

Book Review

Book Review

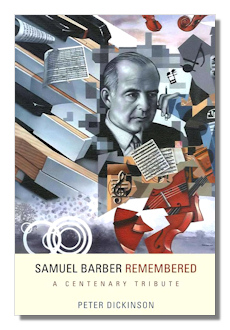

Samuel Barber Remembered

A Centenary Tribute

Edited by Peter Dickinson

Foreword by John Corigliano.

University of Rochester Press 2010

Eastman Studies in Music

General index and index of works.

Illustrations. 196 pages.

ISBN-10: 1580463509

ISBN-13: 978-1580463508

Shortly after Barber's death, which occurred early in 1991, BBC Radio 3 finally approved a one hour documentary which had previously been proposed by its music producer Arthur Johnson. The British composer and pianist, Peter Dickinson, who headed the Centre for American Music at the University of Keele, was persuaded to take on the role of presenter. Johnson writes briefly here about this background, and also contributes an interview he had with Robert White in London during February 1991; Barber had been a friend of White and his family from 1961 until the end of Barber's life.

In April 1991 Dickinson interviewed Gian Carlo Menotti in Scotland and in May Dickinson went to New York and interviewed eleven prominent people, variously associated with Barber, in the course of five days. It is these interviews, published in full for the first time, which comprise the bulk of this book. There are also interviews with Barber, from 1949, 1978 and 1979 by various people; and an interview from 2005 – one of the most interesting – with the then 97-year-old cellist Orlando Cole, (born two years before Barber and still living) who knew Barber since the 1930's when they were both among the very first enrollees as students at the new Curtis Institute. Additionally, there are two chapters by Dickinson, on Barber's early life and about the (mostly lukewarm) early musical attitudes to Barber in Britain.

What is perhaps most valuable about this collection is the immediacy of the interviewees' impressions of Barber the man and musician. Most of them knew him well and they spoke frankly about him. They are grouped as friends, fellow composers, performers, publishers and critics.

As a person, Barber comes through as cultivated and urbane, fluent in several languages, with strong emotions expressed in his music more than verbally. He was witty and entertaining, sometimes at the expense of others, and frank in telling his friends what he thought, though reportedly they generally did not mind. Evidently he showed a temper at times but was kind and generous to many, particularly to performers, including John Browning and Leontyne Price, who, in return, had the warmest regard for him. During the technically disastrous opening night of Antony and Cleopatra at the inaugural night of the new Met at Lincoln Center, when things went so wrong as to imprison her on stage in something variously described as a Sphinx or Pyramid, she sang her heart out anyway to make sure Barber's music went forward.

That disastrous premiere, by the way, is unanimously blamed mainly on the elaborate production by Zeffirelli, who also produced a libretto without a love scene – later written for the successful run of Antony and Cleopatra at Juilliard, for which the music was both cut and expanded, with a love scene added and with the libretto re-written by Menotti.

There is universal agreement that Barber the composer had a tremendous technical mastery and command of his art. He had great ability to create long lines and was especially skilled in counterpoint, in which he had been drilled by his only composition teacher, Rosario Scalero, whom Cole describes as "a very austere, old-fashioned type of Herr Professor." Scalero had studied in Vienna with a friend of Brahms. Undoubtedly this accounts in great part for the kind of music Barber produced, though Barber's romantic temperament gave him no reason to rebel against this kind of training. As it happens, and I did not know this, Barber actually did make use of some twelve tone effects later and reportedly there was a copy of Schoenberg's Piano Concerto on Barber's piano when he was writing his own concerto for that instrument, but he seems always to have been content to go his own way, regardless of musical trends or the opinions of others, unlike Copland who began and ended his career sympathetic to ideals of radical innovation. And he was definitely interested in pleasing the public, as performers perforce are. Everyone seems to agree that Barber was uninfluenced by Menotti's music (a question frequently raised here) but the reverse might have been the case.

Here is the crux of the response to Barber's music, divided between audiences, which have always loved Barber's music, and critics and other composers who often scorned it as old-fashioned. The music historian H. Wiley Hitchcock shows his own preference when he notes that historians are interested in change and trend-setters rather than composers like Bach, Brahms and Barber, who remained closely within a tradition and did not have close followers. Neither Copland nor Virgil Thomson, in their interviews seems entirely lacking in scorn for Barber's conservatism, as conservative as much of their own music is, though they recognized how good he was at what he chose to do. When asked which of Barber's works would endure, Thomson, a long-time critic, responded, "How would I know?" William Schuman shows himself much more kindly disposed to Barber and in fact was one of those present at Barber's final sickbed concert.

As for which works most impressed these interviewees generally, Schuman and others expressed high regard to Vanessa. The Cello Concerto, perhaps surprisingly, was frequently mentioned. And naturally, the Adagio for Strings, one of the most successful pieces of all time, was praised as a formally perfect piece and intense expression of feeling, though interpretations differed. It has often been associated with grief, but Thomson gave a sexual interpretation of it. Dickinson pursued the reasons for its appeal with each interviewee. Other frequently mentioned works included the songs and piano music, Knoxville, Summer of 1915, and the early orchestral works. The Violin Concerto, surprisingly, was hardly brought up, though Cole gives probably the most explicit account of its origins that I've seen.

Barber was loyal to his sole publisher, Schirmer, throughout his life, and Schirmer was good to him, actually keeping him on retainer. To be sure, Barber's works, especially the Adagio for Strings, made a lot of money for both parties. His sales grew steadily and never dipped over the years and Barber's estate was worth a million dollars in 1981. (He had come from a wealthy, patrician family originally, which may have amplified this prosperity.) Both interviewees from Schirmer praised Barber's professionalism. His output was not large: typically a major work and a few minor works annually. He worked slowly, methodically, and impeccably till about fifteen years before his death.

Factors in Barber's later non-productivity were chiefly the Antony and Cleopatra disaster; the sale of Capricorn, the house in the countryside he and Menotti had shared, with Barber moving to New York City; and the breakup of that thirty-year relationship. Barber loved Menotti all his life and ended by dying in Menotti's arms. Meanwhile Menotti had moved to Scotland, explaining the breakup by saying that that they had not been getting along, and explaining his surprising move to Scotland as an effort to break with his own entire past. Barber pretty much stopped writing, notably producing only The Lovers, the third Essay for Orchestra and the central movement of an oboe concerto, orchestrated by Barber's friend Charles Turner, and called Canzonetta for Oboe and Strings. There is no mention of other factors in Barber's non-productivity during these years, as has been suggested elsewhere. Incidentally, there is almost no mention in this book of his homosexuality, except that Cole, when asked, said it had never been an issue at Curtis, owing to the fact that Barber was socially impeccable.

Physically, this book is handsome, strongly bound with semi-gloss acid-free paper. I found it pleasurable to read and can strongly recommend it. It is also stongly endorsed by Barbara Heyman, Barber's biographer and by Vivian Perlis, Copland's biographer and the founding director of Yale's Oral History, American Music Archive.

Copyright © 2010 by R. James Tobin.