The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

-

Introduction

Acoustics

Ballet

Biographies

Chamber Music

Composers & Composition

Conducting

Criticism & Commentary

Discographies & CD Guides

Fiction

History

Humor

Illustrations & Photos

Instrumental

Lieder

Music Appreciation

Music Education

Music Industry

Music and the Mind

Opera

Orchestration

Reference Works

Scores

Thematic Indices

Theory & Analysis

Vocal Technique

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

Book Review

Book Review

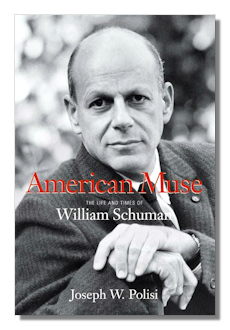

American Muse

The Life and Times of William Schuman

Joseph W. Polisi

New York: Amadeus Press. 2008. 595 pages.

ISBN-10: 1574671731

ISBN-13: 978-1574671731

This is the biography I have been waiting many years for. When, in the 1990's, major biographies appeared of Barber, Bernstein, Britten, Copland and Virgil Thomson, I wondered when someone would get around to publishing one about William Schuman. The prominence and importance of this man and his musical and administrative career demanded one. Happily, a capable and informed writer, Joseph Polisi, President of Juilliard, where Schuman had also been President, was in a position to do the job and get it published. His book is an objective, detailed and chronological account of Schuman's life and work, from which I have learned much I did not know, especially about the music. Although the title promises the "times" as well, there is not so much about that once past the times of Schuman's ancestors, except for the institutional and urban changes, especially concerning Lincoln Center, of which Schuman was so much a part.

Polisi's approach to biography is fact based narration, in great – sometimes redundant – detail. He had access to Schuman's oral histories and family documents, as well as to many who knew Schuman. He is sympathetic to his subject, though not blindly so. He notes, for instance, that Schuman was sometimes regarded as arrogant. He also provides much evidence of Schuman's verbal wit and his stories are often downright funny. This helps the reader get through the blow by blow accounts of the grief that administrative work typically involves.

My own interest in Schuman goes back to when I heard his New England Triptych soon after it was written and recorded. Later, having acquired and mostly abandoned an enthusiasm for the avant-garde, I admired Schuman for keeping true to his own neoclassical aesthetics, regardless of the trends among his peers – and students. Schuman even used old forms, though newly interpreted. Polisi relates how Schuman told his students that he had once been radical, was presently middle-=20=

of-the-road, and expected to be on the right before he died. One brave student politely observed that he was already there. One factor in Schuman's resistance to serialism was his patriotic rejection of what he saw as a Eurocentric movement. He wanted to write American music and deplored the failure of American orchestras to play much American music.

There is significant discussion in this book of Schuman's musical style. It is well known that Schuman began his musical career as a teenager with a jazz band but was so overwhelmed by the sound of a symphony orchestra when he first heard one that he immediately decided he wanted to be a classical composer. What is less often noted is that his "serious" music is devoid of jazz influences; Polisi does note this. Polisi also explains musically just what it was about Schuman's early symphonies that led him to suppress them, among other works. Polisi makes a valuable contribution toward the understanding of Schuman's musical style – which was misunderstood even by accomplished musicians – by showing the roots of his (often dissonant) harmony in contrapuntal or polyphonic, rather than vertical, terms. Schuman said, "I do not use harmony as a device for musical progression, but as an environmental factor for the kind of horizontal sounds that I am interested in at that particular moment." Polisi also notes Schuman's tendency toward extremely slow tempos and really loud dynamics – even to the point of bombast. Polisi shows that his music was melodic and expressive, even passionate, though that quality was frequently denied or not observed by his contemporaries.

Schuman's creative methods are clearly evident in Polisi's account. He was happy to write in response to commissions but, unlike, say Stravinsky, he felt a deep need to write music just because it was something he had to do. His identity was tied up with being a composer. Even when he had enormously demanding jobs as head of Juilliard and Lincoln Center, he made it clear that he needed to compose a thousand – or at least six hundred – hours a year. But he could not compose all day long and he also felt that he had to do other things. Hence his administrative careers. When he composed a work he wrote it straight through in order to the end, unlike Copland who liked to work on pieces out of sequence. Polisi gives us considerable musical analysis, accessible to the lay reader, of many of Schuman's compositions in their chronological sequence as Schuman wrote them. The circumstances of their composition is also given in context, something that one particularly appreciates in a composer's biography. Discussion of the ballets and (mostly unsuccessful) operas stand out here, but so do all the symphonies and many choral works. Works for band and for young players of limited accomplishment are also mentioned. I was reminded of Holst in this regard. One of Schuman's works was actually written in sections for players of beginning, middling and advanced ability.

Schuman was a man of enormous drive, energy and ambition, as well as a brilliant and persuasive speaker. He was tremendously innovative as an administrator, founding numerous programs at Juilliard and Lincoln Center, often in defiance of fiscal restraints that governing boards were naturally concerned with. He felt that, to achieve artistic and aesthetic excellence, fiscal deficits were not only inevitable but even desirable. Naturally this led to serious conflicts and ultimately to the end of his career at Lincoln Center. (A heart attack did not help.) Several of Schuman's musician friends were horrified that he had accepted the job, in the light of what they knew about what he would be facing. A significant source of institutional conflict at Lincoln Center stemmed from Schuman's – and Rockefeller's – concept of Lincoln Center as being greater than the sum of its parts, and the role of Lincoln Center's management as much more than taking care of the theaters used by the constituent performing arts groups. Schuman saw his function as providing creative cultural leadership in the New York City community and he succeeded in that to a great degree. A measure of Schuman's lifetime achievement as composer and administrator was the large number of honorary doctorates and other honors he received that testified to his many accomplishments. Among other things he was responsible for establishing the Juillard String Quartet, Juilliard's dance and drama divisions, the Film Society of Lincoln Center, Mostly Mozart and the Chamber Music Society. He was also responsible for Juilliard's move to Lincoln Center. Of himself, he wrote that "the fact of my life that might be worth recording is the fantastic variety of my experience."

The bulk of the book is about Schuman's public life. He was a very public man and a powerful one who influenced cultural history. But his private life is not ignored. Schuman was fortunate in his marriage. His wife of many years, Frankie, even managed, as a friend said, to "keep him in line when his natural exuberance [ran] away with him." She permitted him to work long hours at home – though not seven days in a week. There were the usual generational conflicts with their children in the late 'Sixties; Schuman even made his son get a haircut before attending one of his father's events. Appearances had to be maintained.

One thing that might have made Polisi's book more accessible to all readers would have been more informative chapter titles and organization. Sometimes it is clear that various chapters are going to be about music or non-musical matters, but not always. Subtitles with dates would have been especially helpful. Nevertheless I never found myself wanting to skip anything.

A valuable contribution to musical biography and history. Recommended.

Copyright © 2010, R. James Tobin