The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

-

Introduction

Acoustics

Ballet

Biographies

Chamber Music

Composers & Composition

Conducting

Criticism & Commentary

Discographies & CD Guides

Fiction

History

Humor

Illustrations & Photos

Instrumental

Lieder

Music Appreciation

Music Education

Music Industry

Music and the Mind

Opera

Orchestration

Reference Works

Scores

Thematic Indices

Theory & Analysis

Vocal Technique

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

Book Review

Book Review

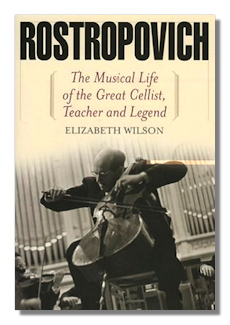

Rostropovich

The Musical Life of the Great Cellist,

Teacher and Legend

Elizabeth Wilson

Chicago: Ivan R. Dee. 2008

ISBN-10: 1566637767

ISBN-13: 9781566637763

Summary for the Busy Executive: Solid biography, enriched by first-hand reminiscences.

Elizabeth Wilson, a British subject and daughter of the British ambassador to Moscow, studied cello with Rostropovich at the Moscow Conservatory from 1964-1971. Among her classmates, one finds Jacqueline du Pré, Mischa Maisky, Natalya Gutman, Stanislav Appolin, Ivan Monighetti, and Moray Welsh. Wilson has also written books on both Jacqueline du Pré and Shostakovich and appears as cellist on ECM's CD of Arvo Pärt's Passio.

This isn't a full biography, in the sense that Galina Vishnevskaya's autobiography is. We get a few details about Rostropovich's family, but Wilson primarily aims to present Rostropovich the teacher – a wise choice, since that Rostropovich she undoubtedly knew best. She admirably keeps herself as much in the background as she can and affords generous space to the reminiscences of others. Her research is diligent and impeccable, and she has gone through many official documents as well as through the cellist's (and his wife's) personal papers.

For me, Rostropovich remains a mystery, despite Wilson. I glimpsed much more of the man in Vishnevskaya's book, but she had a tremendous advantage. This book portrays a "public" Rostropovich, the man of vast reserves of mental and physical stamina, phenomenal memory, and supreme musicianship, the great teacher. He learned difficult new concertos in a few days, and not just the cello part, either. He would set similar tasks for his students and expected them not only to play from memory, but to know what the oboe played in measures so-and-so. He would throw difficult challenges at them while they played ("Play the movement a half-tone lower") and required them to cope. He seldom taught one-on-one, and his open classroom encouraged other musicians to sit in. If nothing else, his students were accustomed to playing for a roomful of critical ears.

Some of this cello "boot camp" mentality I suspect came out of the Soviet system of competitions. If you could survive Rostropovich's class, the Tchaikovsky or All-Union was, comparatively, a piece of cake. Yet his teaching persona wasn't that of a drill sergeant. He invited his students to explore with him, often assigning students the same concerto he was currently learning. He expected consummate professionalism, and he acted as a friend (when he first started teaching, in his teens, some of his pupils were older than he was) and guide. In a certain sense, Rostropovich didn't teach cello, or at least not the mechanics of playing, although he would suggest certain things to each player. Technique as such didn't interest him. He assumed you had it. If you didn't, you worked with his assistant until you came up to the mark. He never started with the fingers or the bow but with a conception of the appropriate sound for the passage. He taught music and musicianship, how to listen, how to analyze, how to connect with the spirit of a work. He emphasized the overall arc of a score and of finding your place in it. Because he was a great musician, a great teacher, and a Mensch besides, he not only gained the love and loyalty of his students, but produced a lot of outstanding cellists.

What most impressed me about Rostropovich this time around was his guile in handling the Soviet bureaucracy. He kept playing "chicken" with the bureaucrats as he stood by Prokofiev and Shostakovich, wagering his prestige and accomplishment against Party vindictiveness and, in some cases, outright terror. In the end, of course, he lost, but he had a remarkably long run. His personal charm (and courage) as well as an army of prestigious foreign friends undoubtedly helped.

To Wilson's enormous credit, this book could have sprawled, and it doesn't. She not only writes very well, she develops large themes across the chapters. Her decision to give over major parts of the book to some of her fellow students helps us see this outgoing, yet enigmatic figure from different perspectives. This isn't "Wilson's Rostropovich," at least not entirely, and that's all to the good. All in all, a fine picture of one of the great figures of his time, and not just in music.

Copyright © 2008 by Steve Schwartz.