The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

-

Introduction

Acoustics

Ballet

Biographies

Chamber Music

Composers & Composition

Conducting

Criticism & Commentary

Discographies & CD Guides

Fiction

History

Humor

Illustrations & Photos

Instrumental

Lieder

Music Appreciation

Music Education

Music Industry

Music and the Mind

Opera

Orchestration

Reference Works

Scores

Thematic Indices

Theory & Analysis

Vocal Technique

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

Book Review

Book Review

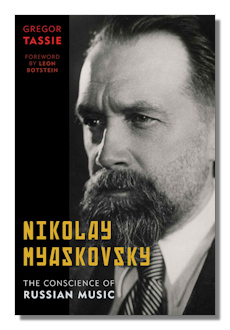

Nikolay Myaskovsky

The Conscience of Russian Music

Gregor Tassie

Foreword by Leon Botstein

Rowman & Litlefield, xviii + 395 pages

Black and white illustrations

ISBN-10: 1442231327

ISBN-13 978-1-4422-3132-0 (cloth, alk. paper)

ISNN 978-1-4422-3133-7 (ebook)

Myaskovsky was one of the leading Russian composers of the last century, and one of the most prolific symphonists of all time, with 26 symphonies to his credit, as well as many string quartets and other works. He was frequently performed in the United States, especially in Chicago, where the Chicago Symphony conductor Frederick Stock revered him, until the cold war and McCarthy era. At that point American performances of his work pretty much ceased, and regrettably have not resumed. In the Soviet Union, where he remained following the 1917 revolution, like Shostakovich and unlike Rachmaninoff, Stravinsky and, for a time, Prokofiev, Myaskovsky was always controversial but frequently performed (not always well) and highly honored – until he was denounced as a "formalist" in the infamous 1948 Zhdanov affair, along with Shostakovich, Prokofiev, Khachaturian and others.

Unlike these other composers who no doubt feared losing their lives as well as their careers, Myaskovsky refused to grovel, or make any defense or statement regarding the very public denunciation (the subject of a book by the journalist Alexander Werth) which was no doubt a major reason for Tassie's subtitle. Myaskovsky's music would speak for him and he simply proceeded to write another symphony. He was not well at the time – nor was Prokofiev – and was to die of cancer only two years later. Zhdanov, who had hopes of succeeding Stalin – something I did not know – died even sooner, in August 1948. A particularly shocking element in this famous episode was the betrayal by Boris Asafyev, a skilled writer and less skilled composer, who had been a good friend to Myaskovsky and Prokofiev until a couple of years before becoming one of the most active participants in the denunciation of the "formalists."

The 1948 denunciations were the culmination of a decades-long struggle between two elements in Russian music, and the temporary triumph of an extreme ideological faction, which had been around since at least the 1920s, and which stood for what became known as socialist realism. In American terms, this was a form of extreme populism, and actually had its roots in the thought of Leo Tolstoy in the nineteenth century. The position of Myaskovsky's opponents was that the arts should always be in the service of social betterment as they saw it; art for art's sake was to be condemned.

For his part, Myaskovsky, actually not a formalist, believed in music as personal expression, which might reflect a concern for what was happening in society – he had an interest in what was going on in the world until his dying days – but he did not shrink from expressing in music his feelings about present realities, which might be tragic or simply awful. This was in contrast to socialist realism which was to portray ideally happy future states of affairs – the way things perhaps ought to be rather than the way they were.

For Myaskovsky, music was his life. Apart from his friends, and a strong appreciation for nature, he appears to have had few interests outside of music. He did serve in various administrative, editorial and teaching roles (he was the teacher of the composers Kabalevsky, Khachaturian and other less famous internationally) but they were all connected with music. He was never interested in getting married, but there is no reason to think he was gay. Unlike Beethoven and Brahms, he was spared the torments of unrequited love. He lived with his sisters. The son of a general (who was killed in a case of mistaken identity) he had a military career early in life, both under the Czar and following the Revolution. He never had much money, and his living arrangements were far from luxurious. It was all he could do to have the use of a decent piano.

Like Prokofiev, ten years younger, for whom he was an early mentor and lifelong friend, as Prokofiev's extensive diaries make clear, Myaskovsky wrote with great facility, turning out some of his works in a remarkably short time. Naturally there were times when he was not sure how he should proceed with a work – particularly if a commission for a vocal work was involved but sometimes with his symphonies – and there was a hiatus or two following difficulties caused by others, but he did not ever suffer from writer's block.

Myaskovsky was a serious man, as most of his photos show, but he was known to smile beautifully on occasion. His friends cared for him intensely. He was kind, a humane man. Tassie sprinkles occasional accounts of his likeability throughout his book but does not devote an extended section about his personality. He does include substantial accounts of Myaskovsky by Mira Mendelson, the second wife of Prokofiev (presumably translated by Tassie, as there is unfortunately no English edition of her diaries.) What Tassie focuses on particularly is well-written accounts of Myaskovsky's individual works, chronologically in the course of his biographical narrative, with full accounts of those he considers especially significant. The benefit for the reader is that one can decide which to seek out especially. Typically, or at least repeatedly, Myaskovsky worked on two contrasting, works at the same time, often one very serious and the other more lyrical.

A revival of Myaskovsky's music, especially in America, is long overdue. It is to be hoped that this excellent book may help bring that about. It has already earned, besides the preface by Leon Botstein, who as conductor has done so much to bring attention to neglected works, the strong endorsements of the composer Oliver Knussen and he conductor Vladimir Jurowski, currently principal conductor of the London Philharmonic Orchestra.

Highly recommended.

Copyright © 2014, R. James Tobin