The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

-

Introduction

Acoustics

Ballet

Biographies

Chamber Music

Composers & Composition

Conducting

Criticism & Commentary

Discographies & CD Guides

Fiction

History

Humor

Illustrations & Photos

Instrumental

Lieder

Music Appreciation

Music Education

Music Industry

Music and the Mind

Opera

Orchestration

Reference Works

Scores

Thematic Indices

Theory & Analysis

Vocal Technique

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

Book Review

Book Review

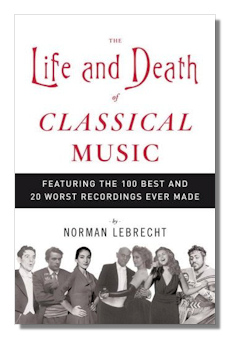

Life and Death of Classical Music

Norman Lebrecht

Anchor Books (2007) 323 pages

ISBN-10: 1400096588

ISBN-13: 978-1400096589

Norman Lebrecht is known for irreverent, often pessimistic, controversial – and entertaining – opinions about music and musicians. Life and Death of Classical Music is his eulogy for – and autopsy of – classical music as seen through the history of its recording industry. Part I is the narrative history. Parts II and III discuss Lebrecht's "100 best and 20 worst recordings ever made" during that history. Lebrecht's wry style is often witty, sometimes gossipy, and rarely reverent. Clever turns of phrase pop from his word processor like dried peas shot through a straw by a cheeky schoolboy.

In the history you will meet a giant of early recording, Fred Gaisberg, who supervised the first discs of a composer's work with the composer on the podium; Walter Legge, who set the standards for the great EMI catalog, and John Culshaw who recorded Wagner's Ring when told no one would be interested. You'll be there when the LP takes over from 78s and when stereo replaces mono. You'll see the emergence of the big money "star" and the corporate control that follows big bucks and often kills the golden goose (though more good recordings came out of this era than Lebrecht would have us believe). Lebrecht's coverage before the corporate takeovers is interesting, with plenty of personalities and anecdotes. The rest of Part I reads like an insouciant business article – good material and anecdotes, but less compelling for a music lover than the material on engineers, producers, and artists. Still you'll find out why Dohnanyi's Ring Cycle was not finished and why Herbert von Karajan, a favorite Lebrecht target, went to EMI after "making" DG.

Conductor Georg Solti was visiting Edward Lewis, chairman of Decca. The phone rang. "That'll be Maurice [Rosengarten, his Director of Recordings]," Lewis said. "How is he?" asked Solti when Lewis returned. "He's dead," replied Lewis.

No one will entirely agree with Lebrecht's "100 best and 20 worst recordings ever made." What counts is he reveals something of each recording's background and artists, again with plenty of anecdotes and insights. What was the horror show behind's Bernstein's infamous recording of Elgar's Enigma Variations? The impulse behind the most famous recording of Vivaldi's Four Seasons?

The Tristan with Wilhelm Furtwangler was almost never recorded because the conductor and "scheming" producer Walter Legge had fallen out. A rapprochement saved the day. After the session, Furtwangler threw his arm around Legge's shoulder and said, "My name will be remembered for this, but yours should be." Legge suggested recording Mahler's Songs of a Wayfarer in the two hours left. "'I promised you Tristan,' the conductor retorted brusquely, 'and that's all you're getting.'"

I part company with Lebrecht in his claim of a musical doomsday and his methodology of relating it to the recording industry. True, both were dealt two serious blows. Before the 1960s, discovering new works was an exciting part of concert-going. Leopold Stokowski and Serge Koussevitsky conducted many premieres (800 for Stokowski), and even the conservative Arturo Toscanini took on a few. Alas, come the 1960s and 70s, composers turned to writing arid pieces for themselves, acolytes, and critics – but not audiences, who rejected most of the new music. For a while (things are better now) classical music was no longer a living art, and that is a phenomenon whose negative effects cannot be overstated.

The second blow was the high retail cost of CDs. (Digital recording is relatively cheap, but corporate excesses and "star" fees are not.) Many consumers fight back by copying CDs and buying them second hand (probably after the original owners copied them). Lebrecht mentions neither ploy but they cost the industry plenty.

And then there's Naxos, the first important digital budget label. Lebrecht tells us quite a bit about Naxos, including its willingness to record any repertoire, hire unknown musicians, and record in places where the "majors" dare not tread, like Eastern Europe, smaller cities in the UK, US, etc. What Naxos did was take advantage of the plenitude of good musicians out there these days. (There are even excellent youth orchestras, e.g., Boston's NEC Youth Philharmonic and the international phenomenon known as the Simón Bolívar Youth Orchestra of Venezuela). Musicians want to record, and they do so on Naxos' terms (a two-edged sword for the musicians). No longer do we need expensive orchestras and stars to make good recordings. Naxos grew into a major label and was joined by many smaller companies. Most did not duplicate Naxos' pricing, but some are more enterprising with repertoire, even to the point of specializing. Many are run by people who know music, and they do not need to sell millions of copies to stay in business. They are recording a wider repertoire than ever (all the symphonies of Milhaud, Arnold, Holmboe, et al., all the operas of Mascagni, et al., not to mention a myriad of opera and concert DVDs, and on and on and on) and more discs, period. This is an age of discovery for collectors. American Record Guide reviews maybe 2500+ items a year, including reissues of older recordings; Fanfare, even more. In calling these labels "cottage" outfits, Lebrecht underrates their importance for they are the future of classical recording.

What Lebrecht seems to miss is that classical music has always been a minority interest – and its minorities are passionate, for great art never dies. As long as there is great music, there will be people to play it and people who want to hear it.

Still, I recommend his book as an introduction to the classical recording industry. It is entertaining and tantalizingly revealing, if not as comprehensive and insightful into the people in front of and behind the microphones as I'd like.

Copyright © 2008 by Roger Hecht.