The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

-

Introduction

Acoustics

Ballet

Biographies

Chamber Music

Composers & Composition

Conducting

Criticism & Commentary

Discographies & CD Guides

Fiction

History

Humor

Illustrations & Photos

Instrumental

Lieder

Music Appreciation

Music Education

Music Industry

Music and the Mind

Opera

Orchestration

Reference Works

Scores

Thematic Indices

Theory & Analysis

Vocal Technique

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

Book Review

Book Review

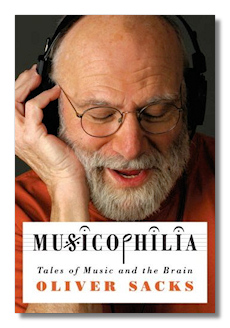

Musicophilia

Tales of Music and the Brain

Oliver Sacks

New York & Toronto: Alfred A. Knopf. 2007. 381 pp

ISBN-10: 1400040817

ISBN-13: 978-1400040810

Summary for the Busy Executive: Sacks at less than his best.

I looked forward to this book. A fan of An Anthropologist on Mars, The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat, Uncle Tungsten, and, of course, Awakenings, I thought Sacks, a classical-music fan, would approach this topic as a busman's holiday.

In a sense, he has, by producing his weakest book. This isn't even a set of case studies, but mostly random observations of various perceptual abnormalities (bad and good) with musical symptoms. There's almost no overarching narrative or even point. Perhaps I'm not Sacks' ideal reader here, since I know little about brain anatomy. The book seemed to me to list abnormalities, barely fleshed out by attaching them to sketches of people (many of them explored in far more depth in Sacks' earlier work), and then pointing to some abnormality in brain response. In other words, musical perceptions arise from the physiology of the brain – normal neural operation as well as that compromised by congenital abnormalities, brain injury, illness, and so on. Well, duh. Although scientists and clinicians would rightfully be grateful for the information, it doesn't make the insight any deeper for the general reader by pointing to, say, the basal ganglia.

The one really interesting notion was how music may alter brain structures or neural operations in injured or abnormal brains, but Sacks never goes into this very deeply. Consequently, there's no suspense, nothing to be revealed or uncovered. It's a litany of facts and limited conjecture. Perhaps we know too little of the mind for Sacks to go any further, but this makes for dull reading.

Sacks could have made up for this lack, as he had in his previous books, by doing what he does best: giving us a fuller sense of the people who exhibit these symptoms, but for the most part, the subjects here are ciphers standing in for a class of patients. Two chapters stand in exception to this general rule: the ones on the former musician and musicologist and now severe amnesiac Clive Wearing and on the Williams Syndrome children. Wearing can't remember from one eye-blink to the next, but when you put a piece of music in front of him, his old skills come back. Sacks returns to form retailing the anxieties, frustrations, fears, and rare joys that come to this man, practically instant by instant. I may be more interested in Williams Syndrome, since I saw a documentary on it featuring a Williams-Syndrome child – a darling, loving little girl. It surprised me to learn that such sufferers (if that's the word) are considered retarded, since that's not the impression I got from this girl – extremely verbal and with social skills far beyond her years, but obviously I have no idea what it's like parenting her day to day.

Overall, however, I must consider the book a disappointment.

Copyright © 2008, Steve Schwartz.