The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

-

Introduction

Acoustics

Ballet

Biographies

Chamber Music

Composers & Composition

Conducting

Criticism & Commentary

Discographies & CD Guides

Fiction

History

Humor

Illustrations & Photos

Instrumental

Lieder

Music Appreciation

Music Education

Music Industry

Music and the Mind

Opera

Orchestration

Reference Works

Scores

Thematic Indices

Theory & Analysis

Vocal Technique

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

Book Review

Book Review

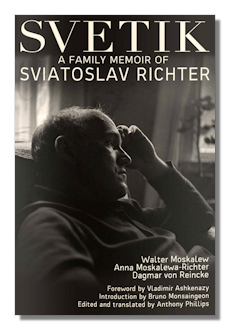

Svetik

A Family Memoir of Sviatoslav Richter

Walter Moskalew [cousin]

Anna Moskalewa-Richter ["Nyuta," mother]

Dagmar von Reincke [Aunt Meri]

Translated and edited by Anthony Phillips

Foreword by Vladimir Ashkenzy

Introduction by Bruno Monsaingeon

"How This Book Came About," Anthony Phillips

Genealogy of the Moskalew Family

Glossary of Names, Index

Toccata Press, 2015. 462 pages.

Profuse illustrations, some in color

ISBN-10: 0907689930

ISBN-13: 978-0907689935

What we have here is a carefully preserved grouping of primary sources about the pianist and – especially – his family. It is not a formal biography, but the authors of the Introduction and Foreword tell us that it fills significant gaps in what was known about Sviatoslav Richter.

Richter was born in 1915, thus in the second year of the First World War and only two years before the Russian Revolution. Both events, especially the German invasion of Russia and then the Stalinist regime, were enormously disruptive of the lives of all the individuals featured here. At the very beginning of the war, Richter's parents were in Vienna on an extended honeymoon, and might well have stayed there, as Richter's father, Theo, was also a musician; but the Sarajevo assassination immediately rendered the couple enemy aliens, as Austria and Russia were at war. Later the couple separated and then divorced. Richter's mother remarried, to a man whom many considered a colossal bore, and whom Richter detested. Meanwhile, one may enjoy an exquisite photo, on page 326, of the infant "Svetik," (as Sviatoslav was invariably called by his family) with his clearly pleased parents. His mother, by the way, although not a classic beauty, was assuredly an extremely lovely and good-looking woman.

The bulk of this volume was written by Richter's younger cousin Walter Moskalew, on the basis of the times he was in a position to know him, particularly on the occasions of Richter's North American concert tours, between 1960 and 1970. He reports on the brilliant successes of Richter's performances but does not memorably dwell on particular works, except for Beethoven's Diabelli Variations. He also recount's Richter's travels to England, Switzerland, Italy, Germany and elsewhere in Europe. Much of Walter's narrative deals with family members other than Svetik.

Sviatoslav's mother's diary also deals with family prior to her son's birth but includes an account of her and Theo's courtship. She reports that Sviatoslav began playing the piano when he was five years old, trying out combinations of notes and chords without instruction, until he could read music. Eventually he had some lessons from a student of his father, and became proficient enough to play the organ in church and to play the piano as an accompanist. He even composed some pieces at a very young age. Additionally he was very interested in drama and art. At age sixteen he became a repetiteur for a ballet company, and was good at judging the abilities of the dancers. The prima ballerina appears to have had an erotic interest in him but nothing came of that. He had an ambition to become a conductor, but that was frustrated by others with ambitions of their own. So instead he was sent to the Moscow Conservatoire, where he passed the entrance examination brilliantly and studied with Professor Neuhaus. What followed were years of separation from his mother.

The final narrative account included here is by Svetik's Aunt Meri, his mother's sister, to whom he became close for the rest of her life, with correspondence between them even when Meri moved to the United States. They shared an interest in art, among other things. This occasioned some sibling rivalry between the mother and the aunt. But what mostly caused that was the great and lengthy geographical separations of the family members, exacerbated by political realities of the time. Sviatoslav, by the way, was completely uninterested in politics or ideology, which undoubtedly kept him safe from the authorities. Even his letters proved of no interest to the censors. He did have minders on his foreign tours, but he had no interest in defecting to the West.

There are two extraordinary unforgettable anecdotes about Richter as a child I feel compelled to relate as illustrations of the character he showed from a young age. At one point two bullies had him against a wall and were beating him until someone intervened. Asked why he did not fight back, he gave the surprising answer, "I am just not that kind of boy."

The other story – the cruelty of which was worthy of Dickens – was related by his Aunt Meri, from Svetik's own account when he was six. One day late in the year he was out playing and found some pebbles, which appealed to him, so he pocketed some. On his way home he passed a house on the back steps of which was sitting a girl his own age. She was very thin and responded to questions about her parents with the fact that she was an orphan. Svetik suggested that they invent a game with his pebbles. What then happened is that a woman came out and yelled at the little girl to come in and take out some slops. The girl came back out with a pail which was so heavy for her underfed frame that she proceeded to spill the contents. When her hasty efforts to pick them up were observed by the woman, she took the girl inside and Svetik heard the girl scream, and sounds of a beating. The girl had told Svetik that she was going to run away, and she did, that evening. When Svetik's family suggested to the orphanage woman that she have the police look for the girl, she declined the suggestion, presumably fearing trouble because of her abusive practices. The story ends with the girl being found and returned to the orphanage the next day. The account has haunted me since.

In spite of the paucity of great detail about Richter's career, there is much to recommend this book in terms of his times and environment. It contains a vast number of excellent photographs, mostly taken over the years by Cousin Walter. Physically, the book is handsomely produced, and distributed by Boydell Press, all the books from which are printed on heavy stock white paper.

Copyright © 2016, R. James Tobin