The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

-

Introduction

Acoustics

Ballet

Biographies

Chamber Music

Composers & Composition

Conducting

Criticism & Commentary

Discographies & CD Guides

Fiction

History

Humor

Illustrations & Photos

Instrumental

Lieder

Music Appreciation

Music Education

Music Industry

Music and the Mind

Opera

Orchestration

Reference Works

Scores

Thematic Indices

Theory & Analysis

Vocal Technique

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

Book Review

Book Review

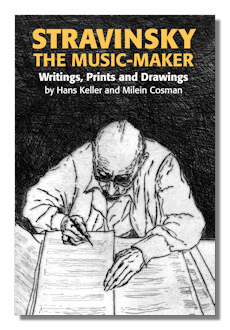

Stravinsky the Music-Maker

Writings, Prints and Drawings

Hans Keller & Milein Cosman

Toccata Press, 242 pp, 2010

ISBN-10: 0907689698

ISBN-13: 978-0907689690

Many European music lovers will know the inspiring work of Austrian emigré, Hans Keller, from his days as a trenchant, highly-accomplished and sometimes uncompromising and provocative speaker (yet never self-important or arrogant) and writer on music in the 1960s and 70s for the then great BBC Radio 3 (formerly The Third Programme) before it lost its way under the current Controller, Roger Wright, and perceived pressure – imaginary or real – to sacrifice any pretentions as a serious arts station to increasing the listenership. Alas, Keller would not have got a look in these days. But his writings endure – many of them shortly to be available again online via an archive of all editions of The Listener from its inception in 1929 to last number in 1991. Boydell imprint Toccata has just issued the third edition of the substantial and informative Stravinsky the Music-Maker: Writings, Prints and Drawing reproducing a collection of nearly 30 of Keller's essays ranging in length from a single page to over 30 pages examining the life and work of Stravinsky, a composer to whom Keller returned more often than any others save Schoenberg and Britten.

There are more comprehensive books on Stravinsky, of course. But this one is to be prized for at least three complementary reasons. In the first place, Keller's style and sense of his responsibilities as someone with insight yet whose greatest role as teacher was to render himself unnecessary mean that his approach is razor sharp, highly communicative, entertaining, rich with context, rich with illusion too – and highly informative. Keller often stimulates us to see the familiar in any one of several at times apparently conflicting, fresh, perspectives; the act of resolving such paradoxes is our "lesson". We have to work.

Secondly, Keller's interest and expertise in psychology and psychoanalysis enrich still further his analyses of Stravinsky in ways that – again – would be unlikely to find favor these days (Keller died in 1985). Nor – as Martin Anderson demonstrates in his introduction – was Keller's use of psychoanalysis in illuminating Stravinsky's life and work that of an amateur or enthusiast alone. He truly was well-equipped to add to our understanding of arguably the twentieth-century's most influential composer, certainly one of the more complex composers, using the insights which that discipline affords.

Thirdly, the drawings, paintings and sketches of Keller's almost life-long companion and wife, Milein Cosman, add an immediacy and a sense of Stravinsky's character and personality to the music which Keller so expertly dissects in his essays. These are not interspersed throughout the text to illustrate any particular theme or musical point (though there are score extracts aplenty – some a little on the small side); rather, they form the last 50 or so (unnumbered) substantive pages of the book. They capture Stravinsky in such characteristic poses, attitudes and actions conducting and watch him engaging in a variety of ways with music, as do indeed add to our sense of what he was during his very productive lifetime.

Stravinsky the Music-Maker: Writings, Prints and Drawing is a version expanded yet again of the book that first appeared as Stravinsky at Rehearsal (1962), then Stravinsky Seen and Heard 20 years later. Now there is more than ever to provide insight into the variety, profundity, breadth and genius (in an interview in the book [p.95] Keller insists on the term, which Stravinsky rejected) of Stravinsky's work. It's meticulously-produced, well-indexed, closely annotated and referenced. And the subjects it deals with range from individual works (the Symphony in Three Movements, Perséphone, the Symphony of Psalms) to the relationships between Stravinsky and Schoenberg, Gershwin and many of the century's composers; how exactly his genius is formed – a particularly insightful essay which also tilts at Adorno and quotes Picasso and Wilde; his concepts of rhythm; serialism; even ways in which he re-used and borrowed in the intriguingly-named chapters, "Stravinsky Eats."

This is not a book about Keller and the rich circle of musicians and artists in which he moved in the postwar years. Not a glossy showcase of images of Stravinsky. It does have Keller's or/and Cosman's stamp on every page. But that's as it should be. By understanding Keller's at times searing sarcasm and penetrating wit – always, always in the service of greater understanding of music – we can get straight to the essence of Stravinsky. Indeed the pictures and prose – for all they're assembled from a disparate selection of mostly previously-published sources – contribute a wonderful composite on Stravinsky. When we connect what Keller and Cosman present about the composer for ourselves, its very apparently unconnected nature triangulates on Stravinsky in ways that a linear biography (such as Stravinsky: The Composer and His Works by Eric Walter White ISBN-10: 0520039858 ISBN-13: 978-0520039858, to a spelling error in an earlier edition of which Keller characteristically draws attention [p.98]) rarely can. Keller believed that the relationship between music and listener was an intimate one. A firm advocate of contemporary music, he once remarked in the introduction he was giving as part of a Third Programme broadcast for the European Broadcasting Union that if the music of David Tudor did nothing other than to inspire you to turn it off (Keller was not so narrow-minded), it had achieved some purpose. So Keller's own larger-than-life personality must come through in his writings. So that personality does in this useful and recommendable book which you should certainly consider adding to your collection if you are interested in Stravinsky's work at all.

Copyright © 2011 by Mark Sealey.