The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

-

Introduction

Acoustics

Ballet

Biographies

Chamber Music

Composers & Composition

Conducting

Criticism & Commentary

Discographies & CD Guides

Fiction

History

Humor

Illustrations & Photos

Instrumental

Lieder

Music Appreciation

Music Education

Music Industry

Music and the Mind

Opera

Orchestration

Reference Works

Scores

Thematic Indices

Theory & Analysis

Vocal Technique

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

Book Review

Book Review

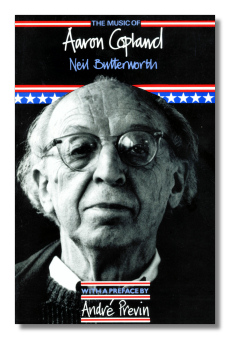

The Music of Aaron Copland

Neil Butterworth

Preface by André Previn

London: Toccata Press. 1985. 262 pp

Also available directly from publisher.

As Shakespeare once wrote, "O for a Muse of fire, that would ascend The brightest heaven of invention." Aaron Copland remains for me one of the finest of all composers, and not just among American and Modern ones. Above all, his music excites me, not merely as an intellectual construct, but as poetry singing of this country and these times. Appalachian Spring and The Tender Land overwhelm me with the nobility of their music, for reasons that have little to do with something one can point to in a score. The same is true for me of every really great composer from Ockeghem to Beethoven to Elgar to Stravinsky and beyond. I really want a meditation on the composer as gripping as the music he writes. What are the odds of that happening?

Furthermore, there aren't all that many books on music for the intelligent, well-heard reader, as opposed to the absolute novice, the scandal-hungry, or the professionally-trained musician. The number of interesting books run in an even smaller herd. Books like Rosen's Classical Style and Romantic Generation, Kennedy's Works of Ralph Vaughan Williams and Portrait of Elgar, or Del Mar's study of Richard Strauss don't come along weekly or even monthly. Furthermore, we now have essentially "tabloid" books merely about how composers carry on in the Big City and not really about music at all. If anyone can tell me one original insight by, say, Joan Peyser into the music of Boulez or Bernstein, I'd be grateful, because I definitely missed it.

As a result, I approach Butterworth's book with certain mixed feelings. It aims at the intelligent, well-heard audience. It zeros in on the music. On the other hand, the style is merely workmanlike. Whatever love Butterworth has for this music remains buried under a mountain of gray, institutional prose. It misses the poetry of Copland's music. For example, Butterworth says of Rodeo:

Its popularity with audiences (and orchestras) is attributable to the direct appeal of melodic and rhythmic invention.

Compare this with Butterworth's quote from Darius Milhaud:

What strikes one immediately in Copland's work is the feeling of the soul of his own country: the wide plains with their soft colourings, where the cowboy sings his nostalgic songs in which, even when the violin throbs and leaps to keep up with the pounding dance rhythms, there is always a tremendous sadness, an underlying distress, which nevertheless does not prevent them from conveying the sense of sturdy strength and sun-drenched movement. His ballet Rodeo gives perfect expression to this truly national art.

Butterworth appends a conversation between Copland and pianist Leo Smit on Copland's piano works, and the interest of the text rockets. Of course it's good that Butterworth includes these quotes, but I really want to know what Butterworth thinks. If I spend time with an author, I do so for that reason. I've already read Milhaud. Furthermore, it is quite obvious that Butterworth has put this work together from index cards. There really is no compelling thesis to carry the reader through the book. We get instead comments about individual pieces in modular units. The editing could also be better. For example, on p. 161, in a discussion of Connotations, we find the following:

Nor is it surprising that Copland should imitate the rhythmic patterns of the Symphonic Ode since he revised that work in 1955.

On p. 165, we read

That Copland should imitate the rhythmic patterns of the Symphonic Ode is not surprising, since he revised the work in 1955…

Déjà vu, dude.

These things aside, the book remains valuable. It does give general analyses of major works, with musical examples to illustrate Butterworth's points. It helps to read music, or at least to be able to plunk out the tunes on a keyboard, for example. As far as I know, there really is nothing available to the general reader, other than Arthur Berger's and Julia Smith's studies, both of which, written in the Fifties, leave out later works. Butterworth is at his best in the later music (weak in the music of the Forties), although here he is plagued by small mistakes. For example, he claims that the Piano Quartet is serial but not 12-tone – that it uses an 11-note row. In Copland since 1943, Copland and Perlis not only don't mention this, but show the full twelve tones – Bb, Ab, Gb Fb D B C# D# E# C G A. Still, Butterworth is especially good at pointing out relationships between serial Copland and The Copland We All Know and Love. What it demonstrates is how Copland always sounds like Copland, whether in tonal motley or serial bar-mitzvah suit.

Copyright © 1997 by Steve Schwartz.